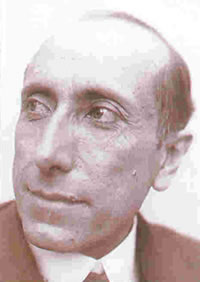

Amado Nervo

Amado Nervo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Juan Crisóstomo Ruiz de Nervo August 27, 1870 Tepic, Nayarit, Mexico |

| Died | May 24, 1919 (aged 48) Montevideo, Uruguay |

| Resting place | Rotunda of Illustrious People in Mexico City, Mexico |

| Occupation | Poet, journalist, educator, Mexican Ambassador to Argentina and Uruguay |

| Language | Spanish |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Period | 19th and 20th centuries |

| Genre | fiction, poetry, essay |

| Subject | writing/poetry |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Spouse | Ana Cecilia Luisa Dailliez (1901–1912) |

Amado Nervo (August 27, 1870 – May 24, 1919) also known as Juan Crisóstomo Ruiz de Nervo, was a Mexican poet, journalist and educator. He also acted as Mexican Ambassador to Argentina and Uruguay.[1] His poetry was known for its use of metaphor and reference to mysticism, presenting both love and religion, as well as Christianity and Hinduism. Nervo is noted as one of the most important Mexican poets of the 19th century.

Early life

[edit]Amado Nervo was born in Tepic, Nayarit in 1870. His father died when Nervo was 5 years old. Two more deaths were to mark his life: the suicide of his brother Luis, who was also a poet, and the death of his wife Ana Cecilia Luisa Dailliez, just 10 years after marriage.

His early studies were at the Colegio San Luis Gonzaga, located in Jacona, Michoacán. After graduation, he began studying at the Roman Catholic Seminary in nearby Zamora. His studies at the seminary included science, philosophy and the first year of law. It was here, that Nervo cultivated an interest in mystical theories, which were reflected in some of his early works.[2]

While Nervo had early plans to join the priesthood, economic hardship led him to accept a desk job in Tepic. He later moved to Mazatlán, where he alternately worked in the office of a lawyer and as a journalist for El Correo de la Tarde (The Evening Mail). He went on to become a successful poet, journalist, and international diplomat.[2]

Professional background

[edit]Writing career

[edit]In 1894, Nervo continued his career in Mexico City, where he became known and appreciated, working in the magazine Azul, with Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera. It was during this time that he was introduced to the work of Luis G. Urbina, Tablada, Dávalos, Rubén Darío, José Santos Chocano, and Campoamor. His background in journalism and news reporting flourished during these years, as he continued writing for El Universal, El Nacional, and El Mundo. He maintained a formal partnership with El Mundo through June 1897.

In October 1897, El Mundo launched a supplement called La Comedia del Mundo, with Nervo taking responsibility for the overall production. In January 1898, the supplement was established independently from El Mundo and changed its name to La Comedia.

Nervo gained a national reputation in the literary community after the publication of his novel El bachiller (The Bachelor) and his books of poetry, including Místicas (Mystical) and Perlas Negras (Black Pearls).

In 1898, Nervo founded, along with Jesús Valenzuela, La Revista Moderna (The Modern Magazine). The magazine was the successor to Azul. He was the cousin of the renowned artist Roberto Montenegro Nervo. His cousin's first illustrations were produced for La Revista Moderna magazine.

In 1902, Nervo wrote "La Raza de Bronce" ("The Bronze Race") in honor of Benito Juárez, former president of Mexico. In 1919, Bolivian writer Alcides Arguedas used the term in his novel, Raza de Bronce. In 1925, the term was used by Mexican luminary José Vasconcelos in his essay, La Raza Cósmica.

Nervo spent the first years of the twentieth century in Europe, particularly in Paris. While there, he was an academic correspondent of the Academia Mexicana de la Lengua. While in Paris, Nervo befriended Enrique Gómez Carrillo and Aurora Cáceres, for whom he wrote a prologue for the book La rosa muerta.

International diplomacy

[edit]When Nervo moved back to Mexico, he was appointed the Mexican Ambassador to Argentina and Uruguay.

Personal background

[edit]In 1901, while he was in Paris he met and married Ana Cecilia Luisa Dailliez. They lived happily until her death in 1912. Out of his grief and desperation, Nervo wrote his most important work, La Amada Inmóvil (The Immovable Loved One), published posthumously in 1922.

There is a rumor that when his wife died he used to go to the cemetery every night for one year.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]Following Amado Nervo's death in Montevideo, Uruguayan president Baltasar Brum ordered that his body be returned to Mexico aboard the cruiser Uruguay[3] and Nervo was interred November 14, 1919, in the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres of Panteón de Dolores, in Mexico City.

Legacy

[edit]- The Amado Nervo Museum displays photos and writings of Nervo. The museum can be found in the home where he was born, on the street which now bears his name.

- A long stretch of the Durango State Highway at San José de Tuitán and Villa Unión, Durango is named after Nervo.

- The Amado Nervo International Airport, the principal airport in the Mexican state of Nayarit, located in Tepic was also named after him.

- The Amado Nervo Institute in Camargo, Chihuahua is a private school, serving kindergarten through junior high school.

- In 1929, Mexican writer, Francisco Monterde wrote a biographical work about Nervo simply titled, Amado Nervo.

- In 1943, Mexican poet, Bernardo Ortiz de Montellano wrote a biographical work about Nervo entitled, Figura, amor y muerte de Amado Nervo.

- In 1961, Argentine composer Julia Stilman-Lasansky used Nervo’s text for her composition Cantata No. 1. [4]

- In 2002, Carlos Monsiváis, the Mexican journalist and political activist wrote an essay entitled, Yo te bendigo, vida, which was about Amado Nervo.[5]

- In 2006, musical artist Rodrigo de la Cadena presented "Poema: Por Cobardia", which was a poem by Nervo's set to music. The song was recorded on de la Cadena's second solo album, Boleros con Orquesta.

Published works

[edit]- El bachiller (The Bachelor) 1895, novel

- El dia que me quieras, poetry

- Perlas Negras (Black Pearls) 1898, poetry

- Místicas (Mystical) 1898, poetry

- Poemas publicada en París (Poems published in Paris) 1901, poetry

- El éxodo y las flores del camino (The Exodus and the Flowers Along the Way) 1902, poetry

- Lira heroica (Heroic Lyre) 1902, poetry

- Los jardines interiores (The Inner Gardens) 1905, poetry

- Almas que pasan (Souls That Pass) 1906, prose

- En voz baja (In Lower Voice) 1909, poetry

- Ellos (Them) prose

- Juana de Asbaje: biografía de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Joan of Asbaje: biography of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz) 1910, essay

- Serenidad (Serenity) 1912, poetry

- Mis filosofías (My Philosophies) 1912, review

- Elevación (Elevation) 1916, poetry

- El diablo desinteresado (The Disinterested Devil) 1916, novel

- Plenitud (Wholeness) 1918, poetry

- El estanque de los lotos (The Lotus Pond) 1919, poetry

- El arquero divino (The Divine Archer) 1919, poetry, published posthumously

- Los balcones (The Balconies) 1920, novel

- La amada inmóvil (The Immovable Loved One) 1922, poetry, published posthumously

- Gratia plena

- Una Esperanza (A Hope)

- Muerto y Resucitado (Dead and Resurrected)

- La raza de bronce (The Bronze Race)

- Éxtasis (Ecstasy)

- El primer beso (The first kiss)

- Poems of Faith and Doubt selection translated by John Gallas, Contemplative Poetry 1 (Oxford: SLG Press, 2021)

References

[edit]- ^ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Inter-America: a monthly that links the thought of the new world, Volume 2, University of Michigan: Inter-America Press, 1919, page 340.

- ^ a b Nervo, Amado (2006) Monday in Mazatlan: 1892-1894 chronicles, works of Amado Nervo, editing, study notes Gustavo Jiménez Aguirre, Mexico, ed. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, pages 21-26. ISBN 970-32-2295-1 Web text accessed September 12, 2011

- ^ Historia y Arqueología Marítima, accessed 2012-02-11.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International Encyclopedia of Women Composers. Books & Music (USA). ISBN 978-0-9617485-0-0.

- ^ "Imposible comprender a México sin Carlos Monsiváis". Milenio. Google Translate. 11 September 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Amado Nervo at the Internet Archive

- Works by Amado Nervo at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)