Alberta

Alberta | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 55°59′30″N 114°22′36″W / 55.99167°N 114.37667°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Before confederation | District of Alberta, District of Assiniboia, District of Athabasca, District of Saskatchewan |

| Confederation | September 1, 1905 (split from NWT) (10th, with Saskatchewan) |

| Capital | Edmonton |

| Largest city | Calgary |

| Largest metro | Calgary Region |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| • Lieutenant governor | Salma Lakhani |

| • Premier | Danielle Smith |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly of Alberta |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 34 of 338 (10.1%) |

| Senate seats | 6 of 105 (5.7%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 661,849 km2 (255,541 sq mi) |

| • Land | 640,082 km2 (247,137 sq mi) |

| • Water | 19,532 km2 (7,541 sq mi) 3% |

| • Rank | 6th |

| 6.6% of Canada | |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 4,368,370[2] |

| • Estimate (Q3 2024) | 4,888,723[3] |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 6.82/km2 (17.7/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Albertan |

| Official languages | English[4][5] |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| • Total (2022) | CA$459.288 billion [6] |

| • Per capita | CA$101,818 (3rd) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2021) | 0.955[7]—Very high (1st) |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (Mountain DST) |

| Canadian postal abbr. | AB |

| Postal code prefix | |

| ISO 3166 code | CA-AB |

| Flower | Wild rose |

| Tree | Lodgepole pine |

| Bird | Great horned owl |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

Alberta is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta borders British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Territories to the north, and the U.S. state of Montana to the south. It is one of the only two landlocked provinces in Canada, with Saskatchewan being the other.[8] The eastern part of the province is occupied by the Great Plains, while the western part borders the Rocky Mountains. The province has a predominantly continental climate but experiences quick temperature changes due to air aridity. Seasonal temperature swings are less pronounced in western Alberta due to occasional Chinook winds.[9]

Alberta is the fourth-largest province by area at 661,848 square kilometres (255,541 square miles),[10] and the fourth-most populous, being home to 4,262,635 people.[2] Alberta's capital is Edmonton, while Calgary is its largest city.[11] The two are Alberta's largest census metropolitan areas.[12] More than half of Albertans live in either Edmonton or Calgary, which contributes to continuing the rivalry between the two cities. English is the official language of the province. In 2016, 76.0% of Albertans were anglophone, 1.8% were francophone and 22.2% were allophone.[13]

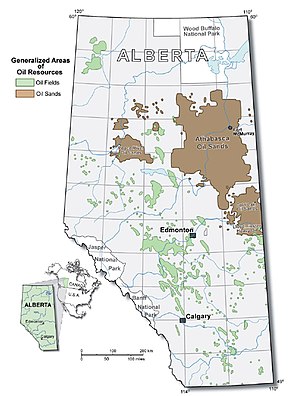

Alberta's economy is based on hydrocarbons, petrochemical industries, livestock and agriculture.[14] The oil and gas industry has been a pillar of Alberta's economy since 1947, when substantial oil deposits were discovered at Leduc No. 1 well.[15] It has also become a part of the province's identity. Since Alberta is the province most rich in hydrocarbons, it provides 70% of the oil and natural gas produced on Canadian soil. In 2018, Alberta's output was CA$338.2 billion, 15.27% of Canada's GDP.[16][17]

Until the 1930s, Alberta's political landscape consisted of two major parties: the centre-left Liberals and the agrarian United Farmers of Alberta. Today, Alberta is generally perceived as a conservative province. The right-wing Social Credit Party held office continually from 1935 to 1971 before the centre-right Progressive Conservatives held office continually from 1971 to 2015, the latter being the longest unbroken run in government at the provincial or federal level in Canadian history.

Since before becoming part of Canada, Alberta has been home to several First Nations like Plains Indians and Woodland Cree. It was also a territory used by fur traders of the rival companies Hudson's Bay Company and North West Company. The Dominion of Canada bought the lands that would become Alberta as part of the NWT in 1870.[18] From the late 1800s to early 1900s, many immigrants arrived to prevent the prairies from being annexed by the United States. Growing wheat and cattle ranching also became very profitable. In 1905, the Alberta Act was passed, creating the province of Alberta.[19] Massive oil reserves were discovered in 1947. The exploitation of oil sands began in 1967.[15]

Alberta is renowned for its natural beauty, richness in fossils and for housing important nature reserves. Alberta is home to six UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites: the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks, Dinosaur Provincial Park, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, Wood Buffalo National Park and Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park.[20] Other popular sites include Banff National Park, Elk Island National Park, Jasper National Park, Waterton Lakes National Park, and Drumheller.

Etymology

[edit]Alberta was named after Princess Louise Caroline Alberta (1848–1939),[21] the fourth daughter of Queen Victoria. Princess Louise was the wife of John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, Governor General of Canada (1878–83). Lake Louise and Mount Alberta were also named in her honour.[22][23]

The name "Alberta" is a feminine Latinized form of Albert, the name of Princess Louise's father, the Prince Consort (cf. Medieval Latin: Albertus, masculine) and its Germanic cognates, ultimately derived from the Proto-Germanic language *Aþalaberhtaz (compound of "noble" + "bright/famous").[24][25]

Geography

[edit]

Alberta, with an area of 661,848 square kilometres (255,541 square miles), is the fourth-largest province after Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia.[26]

Alberta's southern border is the 49th parallel north, which separates it from the U.S. state of Montana. The 60th parallel north divides Alberta from the Northwest Territories. The 110th meridian west separates it from the province of Saskatchewan; while on the west its boundary with British Columbia follows the 120th meridian west south from the Northwest Territories at 60°N until it reaches the Continental Divide at the Rocky Mountains, and from that point follows the line of peaks marking the Continental Divide in a generally southeasterly direction until it reaches the Montana border at 49°N.[27]

The province extends 1,223 kilometres (760 miles) north to south and 660 kilometres (410 miles) east to west at its maximum width. Its highest point is 3,747 metres (12,293 feet) at the summit of Mount Columbia in the Rocky Mountains along the southwest border while its lowest point is 152 metres (499 feet) on the Slave River in Wood Buffalo National Park in the northeast.[28]

With the exception of the semi-arid climate of the steppe in the south-eastern section, the province has adequate water resources. There are numerous rivers and lakes in Alberta used for swimming, fishing and a range of water sports. There are three large lakes, Lake Claire (1,436 km2 [554 sq mi]) in Wood Buffalo National Park, Lesser Slave Lake (1,168 km2 [451 sq mi]), and Lake Athabasca (7,898 km2 [3,049 sq mi]), which lies in both Alberta and Saskatchewan. The longest river in the province is the Athabasca River, which travels 1,538 km (956 mi) from the Columbia Icefield in the Rocky Mountains to Lake Athabasca.[29]

The largest river is the Peace River with an average flow of 2,100 m3/s (74,000 cu ft/s).[30] The Peace River originates in the Rocky Mountains of northern British Columbia and flows through northern Alberta and into the Slave River, a tributary of the Mackenzie River.

Alberta's capital city, Edmonton, is at about the geographic centre of the province. It is the most northerly major city in Canada and serves as a gateway and hub for resource development in northern Canada. With its proximity to Canada's largest oil fields, the region has most of western Canada's oil refinery capacity. Calgary is about 280 km (170 mi) south of Edmonton and 240 km (150 mi) north of Montana, surrounded by extensive ranching country. Almost 75% of the province's population lives in the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor. The land grant policy to the railways served as a means to populate the province in its early years.[31]

Most of the northern half of the province is boreal forest, while the Rocky Mountains along the southwestern boundary are largely temperate coniferous forests of the Alberta Mountain forests and Alberta–British Columbia foothills forests. The southern quarter of the province is prairie, ranging from shortgrass prairie in the southeastern corner to mixed grass prairie in an arc to the west and north of it. The central aspen parkland region extending in a broad arc between the prairies and the forests, from Calgary, north to Edmonton, and then east to Lloydminster, contains the most fertile soil in the province and most of the population. Much of the unforested part of Alberta is given over either to grain farming or cattle ranching, with mixed farming more common in the north and centre, while ranching and irrigated agriculture predominate in the south.[32]

The Alberta badlands are in southeastern Alberta, where the Red Deer River crosses the flat prairie and farmland, and features deep canyons and striking landforms. Dinosaur Provincial Park, near Brooks, showcases the badlands terrain, desert flora, and remnants from Alberta's past when dinosaurs roamed the then lush landscape.

Climate

[edit]

Alberta extends for over 1,200 km (750 mi) from north to south; its climate, therefore, varies considerably. Average high temperatures in January range from 0 °C (32 °F) in the southwest to −24 °C (−11 °F) in the far north. The presence of the Rocky Mountains also influences the climate to the southwest, which disrupts the flow of the prevailing westerly winds and causes them to drop most of their moisture on the western slopes of the mountain ranges before reaching the province, casting a rain shadow over much of Alberta. The northerly location and isolation from the weather systems of the Pacific Ocean cause Alberta to have a dry climate with little moderation from the ocean. Annual precipitation ranges from 300 mm (12 in) in the southeast to 450 mm (18 in) in the north, except in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains where total precipitation including snowfall can reach 600 mm (24 in) annually.[28][33]

Northern Alberta is mostly covered by boreal forest and has a subarctic climate. The agricultural area of southern Alberta has a semi-arid steppe climate because the annual precipitation is less than the water that evaporates or is used by plants. The southeastern corner of Alberta, part of the Palliser Triangle, experiences greater summer heat and lower rainfall than the rest of the province, and as a result, suffers frequent crop yield problems and occasional severe droughts. Western Alberta is protected by the mountains and enjoys the mild temperatures brought by winter Chinook winds. Central and parts of northwestern Alberta in the Peace River region are largely aspen parkland, a biome transitional between prairie to the south and boreal forest to the north.

Alberta has a humid continental climate with warm summers and cold winters. The province is open to cold Arctic weather systems from the north, which often produce cold winter conditions. As the fronts between the air masses shift north and south across Alberta, the temperature can change rapidly. Arctic air masses in the winter produce extreme minimum temperatures varying from −54 °C (−65 °F) in northern Alberta to −46 °C (−51 °F) in southern Alberta, although temperatures at these extremes are rare.

In the summer, continental air masses have produced record maximum temperatures from 32 °C (90 °F) in the mountains to over 40 °C (104 °F) in southeastern Alberta.[34] Alberta is a sunny province. Annual bright sunshine totals range between 1,900 up to just under 2,600 hours per year. Northern Alberta gets about 18 hours of daylight in the summer.[34] The average daytime temperatures range from around 21 °C (70 °F) in the Rocky Mountain valleys and far north, up to around 28 °C (82 °F) in the dry prairie of the southeast. The northern and western parts of the province experience higher rainfall and lower evaporation rates caused by cooler summer temperatures. The south and east-central portions are prone to drought-like conditions sometimes persisting for several years, although even these areas can receive heavy precipitation, sometimes resulting in flooding.

In the winter, the Alberta clipper, a type of intense, fast-moving winter storm that generally forms over or near the province and, pushed with great speed by the continental polar jetstream, descends over the rest of southern Canada and the northern tier of the United States.[35] In southwestern Alberta, the cold winters are frequently interrupted by warm, dry Chinook winds blowing from the mountains, which can propel temperatures upward from frigid conditions to well above the freezing point in a very short period. During one Chinook recorded at Pincher Creek, temperatures soared from −19 to 22 °C (−2 to 72 °F) in just one hour.[28] The region around Lethbridge has the most Chinooks, averaging 30 to 35 Chinook days per year. Calgary has a 56% chance of a white Christmas, while Edmonton has an 86% chance.[36]

After Saskatchewan, Alberta experiences the most tornadoes in Canada with an average of 15 verified per year.[37] Thunderstorms, some of them severe, are frequent in the summer, especially in central and southern Alberta. The region surrounding the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor is notable for having the highest frequency of hail in Canada, which is caused by orographic lifting from the nearby Rocky Mountains, enhancing the updraft/downdraft cycle necessary for the formation of hail.

| Community | Region | July daily maximum[38] |

January daily maximum[38] |

Annual precipitation[38] |

Plant hardiness zone[39] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicine Hat | Southern Alberta | 28 °C (82 °F) | −3 °C (27 °F) | 323 mm (12.7 in) | 4b |

| Brooks | Southern Alberta | 28 °C (82 °F) | −4 °C (25 °F) | 301 mm (11.9 in) | 4a |

| Lethbridge | Southern Alberta | 26 °C (79 °F) | 0 °C (32 °F) | 380 mm (15 in) | 4b |

| Fort McMurray | Northern Alberta | 24 °C (75 °F) | −12 °C (10 °F) | 419 mm (16.5 in) | 3a |

| Wetaskiwin | Central Alberta | 24 °C (75 °F) | −5 °C (23 °F) | 497 mm (19.6 in) | 3b |

| Edmonton | Edmonton Metropolitan Region | 23 °C (73 °F) | −6 °C (21 °F) | 456 mm (18.0 in) | 4a |

| Cold Lake | Northern Alberta | 23 °C (73 °F) | −10 °C (14 °F) | 421 mm (16.6 in) | 3a |

| Camrose | Central Alberta | 23 °C (73 °F) | −6 °C (21 °F) | 438 mm (17.2 in) | 3b |

| Fort Saskatchewan | Edmonton Metropolitan Region | 23 °C (73 °F) | −7 °C (19 °F) | 455 mm (17.9 in) | 3b |

| Lloydminster | Central Alberta | 23 °C (73 °F) | −10 °C (14 °F) | 409 mm (16.1 in) | 3a |

| Red Deer | Central Alberta | 23 °C (73 °F) | −5 °C (23 °F) | 486 mm (19.1 in) | 4a |

| Grande Prairie | Northern Alberta | 23 °C (73 °F) | −8 °C (18 °F) | 445 mm (17.5 in) | 3b |

| Leduc | Edmonton Metropolitan Region | 23 °C (73 °F) | −6 °C (21 °F) | 446 mm (17.6 in) | 3b |

| Calgary | Calgary Metropolitan Region | 23 °C (73 °F) | −1 °C (30 °F) | 419 mm (16.5 in) | 4a |

| Chestermere | Calgary Metropolitan Region | 23 °C (73 °F) | −3 °C (27 °F) | 412 mm (16.2 in) | 3b |

| St. Albert | Edmonton Metropolitan Region | 22 °C (72 °F) | −6 °C (21 °F) | 466 mm (18.3 in) | 4a |

| Lacombe | Central Alberta | 22 °C (72 °F) | −5 °C (23 °F) | 446 mm (17.6 in) | 3b |

Ecology

[edit]Flora

[edit]

In central and northern Alberta the arrival of spring is marked by the early flowering of the prairie crocus (Pulsatilla nuttalliana) anemone; this member of the buttercup family has been recorded flowering as early as March, though April is the usual month for the general population.[40] Other prairie flora known to flower early are the golden bean (Thermopsis rhombifolia) and wild rose (Rosa acicularis).[41] Members of the sunflower (Helianthus) family blossom on the prairie in the summer months between July and September.[42] The southern and east central parts of Alberta are covered by short prairie grass,[43] which dries up as summer lengthens, to be replaced by hardy perennials such as the prairie coneflower (Ratibida), fleabane, and sage (Artemisia). Both yellow and white sweet clover (Melilotus) can be found throughout the southern and central areas of the province.

The trees in the parkland region of the province grow in clumps and belts on the hillsides. These are largely deciduous, typically aspen, poplar, and willow. Many species of willow and other shrubs grow in virtually any terrain. North of the North Saskatchewan River, evergreen forests prevail for thousands of square kilometres. Aspen poplar, balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera) or in some parts cottonwood (Populus deltoides), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera) are the primary large deciduous species. Conifers include jack pine (Pinus banksiana), Rocky Mountain pine, lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), both white and black spruce, and the deciduous conifer tamarack (Larix laricina).

Fauna

[edit]

The four climatic regions (alpine, boreal forest, parkland, and prairie) of Alberta are home to many different species of animals. The south and central prairie was the homeland of the American bison, also known as buffalo, with its grasses providing pasture and breeding ground for millions of buffalo. The buffalo population was decimated during early settlement, but since then, buffalo have made a comeback, living on farms and in parks all over Alberta.

Herbivores are found throughout the province. Moose, mule deer, elk, and white-tailed deer are found in the wooded regions, and pronghorn can be found in the prairies of southern Alberta. Bighorn sheep and mountain goats live in the Rocky Mountains. Rabbits, porcupines, skunks, squirrels, and many species of rodents and reptiles live in every corner of the province. Alberta is home to only one venomous snake species, the prairie rattlesnake.

Alberta is home to many large carnivores such as wolves, grizzly bears, black bears, and mountain lions, which are found in the mountains and wooded regions. Smaller carnivores of the canine and feline families include coyotes, red foxes, Canada lynx, and bobcats. Wolverines can also be found in the northwestern areas of the province.

Central and northern Alberta and the region farther north are the nesting ground of many migratory birds. Vast numbers of ducks, geese, swans and pelicans arrive in Alberta every spring and nest on or near one of the hundreds of small lakes that dot northern Alberta. Eagles, hawks, owls, and crows are plentiful, and a huge variety of smaller seed and insect-eating birds can be found. Alberta, like other temperate regions, is home to mosquitoes, flies, wasps, and bees. Rivers and lakes are populated with pike, walleye, whitefish, rainbow, speckled, brown trout, and sturgeon. Native to the province, the bull trout, is the provincial fish and an official symbol of Alberta. Turtles are found in some water bodies in the southern part of the province. Frogs and salamanders are a few of the amphibians that make their homes in Alberta.

Alberta is the only province in Canada — as well as one of the few places in the world — that is free from Norwegian rats.[44] Since the early 1950s, the Government of Alberta has operated a rat-control program, which has been so successful that only isolated instances of wild rat sightings are reported, usually of rats arriving in the province aboard trucks or by rail. In 2006, Alberta Agriculture reported zero findings of wild rats; the only rat interceptions have been domesticated rats that have been seized from their owners. It is illegal for individual Albertans to own or keep Norwegian rats of any description; the animals can only be kept in the province by zoos, universities and colleges, and recognized research institutions. In 2009, several rats were found and captured, in small pockets in southern Alberta,[45] putting Alberta's rat-free status in jeopardy. A colony of rats was subsequently found in a landfill near Medicine Hat in 2012 and again in 2014.[46][47]

Paleontology

[edit]

Alberta has one of the greatest diversities and abundances of Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils worldwide.[48] Taxa are represented by complete fossil skeletons, isolated material, microvertebrate remains, and even mass graves. At least 38 dinosaur type specimens were collected in the province. The Foremost Formation, Oldman Formation and Dinosaur Park Formations collectively comprise the Judith River Group and are the most thoroughly studied dinosaur-bearing strata in Alberta.[48]

Dinosaur-bearing strata are distributed widely throughout Alberta.[48] The Dinosaur Provincial Park area contains outcrops of the Dinosaur Park Formation and Oldman Formation. In Alberta's central and southern regions are intermittent Scollard Formation outcrops. In the Drumheller Valley and Edmonton regions there are exposed Horseshoe Canyon facies. Other formations have been recorded as well, like the Milk River and Foremost Formations. The latter two have a lower diversity of documented dinosaurs, primarily due to their lower total fossil quantity and neglect from collectors who are hindered by the isolation and scarcity of exposed outcrops. Their dinosaur fossils are primarily teeth recovered from microvertebrate fossil sites. Additional geologic formations that have produced only a few fossils are the Belly River Group and St. Mary River Formations of the southwest and the northwestern Wapiti Formation, which contains two Pachyrhinosaurus bone beds. The Bearpaw Formation represents strata deposited during a marine transgression. Dinosaurs are known from this formation, but represent specimens washed out to sea or reworked from older sediments.[48]

History

[edit]

Paleo-Indians arrived in Alberta at least 10,000 years ago, toward the end of the last ice age. They are thought to have migrated from Siberia to Alaska on a land bridge across the Bering Strait and then possibly moved down the east side of the Rocky Mountains through Alberta to settle the Americas. Others may have migrated down the coast of British Columbia and then moved inland.[49] Over time they differentiated into various First Nations peoples, including the Plains Indians of southern Alberta such as those of the Blackfoot Confederacy and the Plains Cree, who generally lived by hunting buffalo, and the more northerly tribes such as the Woodland Cree and Chipewyan who hunted, trapped, and fished for a living.[28]

The first Europeans to visit Alberta were French Canadians during the late 18th century, working as fur traders. French was the predominant language used in some early fur trading forts in the region, such as the first Fort Edmonton (in present-day Fort Saskatchewan). After the British arrival in Canada, approximately half of the province of Alberta, south of the Athabasca River drainage, became part of Rupert's Land which consisted of all land drained by rivers flowing into Hudson Bay. This area was granted by Charles II of England to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) in 1670, and rival fur trading companies were not allowed to trade in it.

The Athabasca River and the rivers north of it were not in HBC territory because they drained into the Arctic Ocean instead of Hudson Bay, and they were prime habitats for fur-bearing animals. The first European explorer of the Athabasca region was Peter Pond, who learned of the Methye Portage, which allowed travel from southern rivers into the rivers north of Rupert's Land. Other North American fur traders formed the North West Company (NWC) of Montreal to compete with the HBC in 1779. The NWC occupied the northern part of Alberta territory. Peter Pond built Fort Athabasca on Lac la Biche in 1778. Roderick Mackenzie built Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca ten years later in 1788. His cousin, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, followed the North Saskatchewan River to its northernmost point near Edmonton, then setting northward on foot, trekked to the Athabasca River, which he followed to Lake Athabasca. It was there he discovered the mighty outflow river which bears his name—the Mackenzie River—which he followed to its outlet in the Arctic Ocean. Returning to Lake Athabasca, he followed the Peace River upstream, eventually reaching the Pacific Ocean, and so he became the first European to cross the North American continent north of Mexico.[50]

The extreme southernmost portion of Alberta was part of the French (and Spanish) territory of Louisiana and was sold to the United States in 1803. In the Treaty of 1818, the portion of Louisiana north of the Forty-Ninth Parallel was ceded to Great Britain.[51]

Fur trade expanded in the north, but bloody battles occurred between the rival HBC and NWC, and in 1821 the British government forced them to merge to stop the hostilities.[52] The amalgamated Hudson's Bay Company dominated trade in Alberta until 1870 when the newly formed Canadian Government purchased Rupert's Land. Northern Alberta was included in the North-Western Territory until 1870, when it and Rupert's land became Canada's North-West Territories.

First Nations negotiated the Numbered Treaties with the Crown in which the Crown gained title to the land that would later become Alberta, and the Crown committed to the ongoing support of the First Nations and guaranteed their hunting and fishing rights. The most significant treaties for Alberta are Treaty 6 (1876), Treaty 7 (1877) and Treaty 8 (1899).

The District of Alberta was created as part of the North-West Territories in 1882. As settlement increased, local representatives to the North-West Legislative Assembly were added. After a long campaign for autonomy, in 1905, the District of Alberta was enlarged and given provincial status, with the election of Alexander Cameron Rutherford as the first premier. Less than a decade later, the First World War presented special challenges to the new province as an extraordinary number of volunteers left relatively few workers to maintain services and production. Over 50% of Alberta's doctors volunteered for service overseas.[53]

On June 21, 2013, during the 2013 Alberta floods Alberta experienced heavy rainfall that triggered catastrophic flooding throughout much of the southern half of the province along the Bow, Elbow, Highwood and Oldman rivers and tributaries. A dozen municipalities in Southern Alberta declared local states of emergency on June 21 as water levels rose and numerous communities were placed under evacuation orders.[54]

In 2016, the Fort McMurray wildfire resulted in the largest fire evacuation of residents in Alberta's history, as more than 80,000 people were ordered to evacuate.[55][56]

From 2020 until restrictions were lifted in 2022, Alberta was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.[57]

Demographics

[edit]

The 2021 Canadian census reported Alberta had a population of 4,262,635 living in 1,633,220 of its 1,772,670 total dwellings, an 4.8% change from its 2016 population of 4,067,175. With a land area of 634,658.27 km2 (245,042.93 sq mi), it had a population density of 6.7/km2 in 2021.[2] Statistics Canada estimated the province to have a population of 4,800,768 in Q1 of 2024.[58]

Since 2000, Alberta's population has experienced a relatively high rate of growth, mainly because of its burgeoning economy. Between 2003 and 2004, the province had high birthrates (on par with some larger provinces such as British Columbia), relatively high immigration, and a high rate of interprovincial migration compared to other provinces.[59]

In 2016, Alberta continued to have the youngest population among the provinces with a median age of 36.7 years, compared with the national median of 41.2 years. Also in 2016, Alberta had the smallest proportion of seniors (12.3%) among the provinces and one of the highest population shares of children (19.2%), further contributing to Alberta's young and growing population.[60]

About 81% of the population lives in urban areas and only about 19% in rural areas. The Calgary–Edmonton Corridor is the most urbanized area in the province and is one of the most densely populated areas of Canada.[61] Many of Alberta's cities and towns have experienced very high rates of growth in recent history.[when?] Alberta's population rose from 73,022 in 1901[62] to 3,290,350 according to the 2006 census.[63]

According to the 2016 census Alberta has 779,155 residents (19.2%) between the ages of 0–14, 2,787,805 residents (68.5%) between the ages of 15–64, and 500,215 residents (12.3%) aged 65 and over.[64]

Additionally, as per the 2016 census, 1,769,500 residents hold a postsecondary certificate, diploma or degree, 895,885 residents have obtained a secondary (high) school diploma or equivalency certificate, and 540,665 residents do not have any certificate, diploma or degree.[64]

Municipalities

[edit]| Census metropolitan areas: | 2016[65] | 2011[66] | 2006[67] | 2001[68] | 1996[69] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary CMA | 1,392,609 | 1,214,839 | 1,079,310 | 951,395 | 821,628 |

| Edmonton CMA | 1,321,426 | 1,159,869 | 1,034,945 | 937,845 | 862,597 |

| Lethbridge CMA | 117,394 | 105,999 | 95,196 | 87,388 | 82,025 |

| Urban municipalities (10 largest): | 2016[70] | 2011[71] | 2006[72] | 2001[73] | 1996[74] |

| Calgary | 1,239,220 | 1,096,833 | 988,193 | 878,866 | 768,082 |

| Edmonton | 932,546 | 812,201 | 730,372 | 666,104 | 616,306 |

| Red Deer | 100,418 | 90,564 | 82,772 | 67,707 | 60,080 |

| Lethbridge | 92,729 | 83,517 | 78,713 | 68,712 | 64,938 |

| St. Albert (included in Edmonton CMA) | 65,589 | 61,466 | 57,719 | 53,081 | 46,888 |

| Medicine Hat | 63,260 | 60,005 | 56,997 | 51,249 | 46,783 |

| Grande Prairie | 63,166 | 55,032 | 47,076 | 36,983 | 31,353 |

| Airdrie (included in Calgary CMA) | 61,581 | 42,564 | 28,927 | 20,382 | 15,946 |

| Spruce Grove (included in Edmonton CMA) | 34,066 | 26,171 | 19,496 | 15,983 | 14,271 |

| Leduc (included in Edmonton CMA) | 29,993 | 24,304 | 16,967 | 15,032 | 14,346 |

| Specialized/rural municipalities (5 largest): | 2016[70] | 2011[71] | 2006[72] | 2001[73] | 1996[74] |

| Strathcona County (included in Edmonton CMA) | 98,044 | 92,490 | 82,511 | 71,986 | 64,176 |

| Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo (includes Fort McMurray) | 71,589 | 65,565 | 51,496 | 42,581 | 35,213 |

| Rocky View County (included in Calgary CMA) | 39,407 | 36,461 | 34,171 | 29,925 | 23,326 |

| Parkland County (included in Edmonton CMA) | 32,097 | 30,568 | 29,265 | 27,252 | 24,769 |

| Municipal District of Foothills No. 31 | 22,766 | 21,258 | 19,736 | 16,764 | 13,714 |

Language

[edit]As of the 2021 Canadian Census, the ten most spoken languages in the province included English (4,109,720 or 98.37%), French (260,415 or 6.23%), Tagalog (172,625 or 4.13%), Punjabi (126,385 or 3.03%), Spanish (116,070 or 2.78%), Hindi (94,015 or 2.25%), Mandarin (82,095 or 1.97%), Arabic (76,760 or 1.84%), Cantonese (74,960 or 1.79%), and German (65,370 or 1.56%).[75] The question on knowledge of languages allows for multiple responses.

As of the 2016 census, English is the most common mother tongue, with 2,991,485 native speakers.[64] This is followed by Tagalog, with 99,035 speakers, German, with 80,050 speakers, French, with 72,150 native speakers, and Punjabi, with 68,695 speakers.[64]

The 2006 census found that English, with 2,576,670 native speakers, was the most common mother tongue of Albertans, representing 79.99% of the population. The next most common mother tongues were Chinese with 97,275 native speakers (3.02%), followed by German with 84,505 native speakers (2.62%) and French with 61,225 (1.90%).[76] Other mother tongues include: Punjabi, with 36,320 native speakers (1.13%); Tagalog, with 29,740 (0.92%); Ukrainian, with 29,455 (0.91%); Spanish, with 29,125 (0.90%); Polish, with 21,990 (0.68%); Arabic, with 20,495 (0.64%); Dutch, with 19,980 (0.62%); and Vietnamese, with 19,350 (0.60%). The most common aboriginal language is Cree 17,215 (0.53%). Other common mother tongues include Italian with 13,095 speakers (0.41%); Urdu with 11,275 (0.35%); and Korean with 10,845 (0.33%); then Hindi 8,985 (0.28%); Persian 7,700 (0.24%); Portuguese 7,205 (0.22%); and Hungarian 6,770 (0.21%).

According to Statistics Canada, Alberta is home to the second-highest proportion (2%) of Francophones in western Canada (after Manitoba). Despite this, relatively few Albertans claim French as their mother tongue. Many of Alberta's French-speaking residents live in the central and northwestern regions of the province, after migration from other areas of Canada or descending from Métis.

Ethnicity

[edit]Alberta has considerable ethnic diversity. In line with the rest of Canada, many are descended from immigrants of Western European nations, notably England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales and France, but large numbers later came from other regions of Europe, notably Germany, Ukraine and Scandinavia.[77]

In the 2006 Canadian census, the most commonly reported ethnic origins among Albertans were: 885,825 English (27.2%); 679,705 German (20.9%); 667,405 Canadian (20.5%); 661,265 Scottish (20.3%); 539,160 Irish (16.6%); 388,210 French (11.9%); 332,180 Ukrainian (10.2%); 172,910 Dutch (5.3%); 170,935 Polish (5.2%); 169,355 North American Indian (5.2%); 144,585 Norwegian (4.4%); and 137,600 Chinese (4.2%). (Each person could choose as many ethnicities as were applicable.)[78] Amongst those of British heritage, the Scots have had a particularly strong influence on place-names, with the names of many cities and towns including Calgary, Airdrie, Canmore, and Banff having Scottish origins.

Both Edmonton and Calgary have historic Chinatowns, and Calgary has Canada's third-largest Chinese community. The Chinese presence began with workers employed in the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s.

In 2021, 27.8% of the population consisted of visible minorities and 6.8% of the population was Indigenous, mostly of First Nations and Métis descent. There was also a small number of Inuit in the province. The Indigenous population has been growing at a faster rate than the population of Alberta as a whole.[79]

Religion

[edit]

According to the 2021 census, religious groups in Alberta included:[80]

- Christianity (2,009,820 persons or 48.1%)

- Irreligion (1,676,045 persons or 40.1%)

- Islam (202,535 persons or 4.8%)

- Sikhism (103,600 persons or 2.5%)

- Hinduism (78,520 persons or 1.9%)

- Buddhism (42,830 persons or 1.0%)

- Indigenous Spirituality (19,755 persons or 0.5%)

- Judaism (11,390 persons or 0.3%)

- Other (33,220 persons or 0.8%)

As of the 2011 National Household Survey, the largest religious group was Roman Catholic, representing 24.3% of the population. Alberta had the second-highest percentage of non-religious residents among the provinces (after British Columbia) at 31.6% of the population. Of the remainder, 7.5% of the population identified themselves as belonging to the United Church of Canada, while 3.9% were Anglican. Lutherans made up 3.3% of the population while Baptists comprised 1.9%.[81]

Members of LDS Church are mostly concentrated in the extreme south of the province. Alberta has a population of Hutterites, a communal Anabaptist sect similar to the Mennonites, and has a significant population of Seventh-day Adventists. Alberta is home to several Byzantine Rite Churches as part of the legacy of Eastern European immigration, including the Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy of Edmonton, and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada's Western Diocese which is based in Edmonton. Muslims made up 3.2% of the population, Sikhs 1.5%, Buddhists 1.2%, and Hindus 1.0%. Many of these are immigrants, but others have roots that go back to the first settlers of the prairies. Canada's oldest mosque, the Al-Rashid Mosque, is in Edmonton,[82] whereas Calgary is home to Canada's largest mosque, the Baitun Nur Mosque.[83] Alberta is also home to a growing Jewish population of about 15,400 people who constituted 0.3% of Alberta's population. Most of Alberta's Jews live in the metropolitan areas of Calgary (8,200) and Edmonton (5,500).[84]

Economy

[edit]

Alberta's economy was one of the strongest in the world, supported by the burgeoning petroleum industry and to a lesser extent, agriculture and technology. In 2013, Alberta's per capita GDP exceeded that of the United States, Norway, or Switzerland,[85] and was the highest of any province in Canada at CA$84,390. This was 56% higher than the national average of CA$53,870 and more than twice that of some of the Atlantic provinces.[86][87] In 2006, the deviation from the national average was the largest for any province in Canadian history.[88] According to the 2006 census,[89] the median annual family income after taxes was $70,986 in Alberta (compared to $60,270 in Canada as a whole). In 2014, Alberta had the second-largest economy in Canada after Ontario, with a GDP exceeding CA$376 billion.[90] The GDP of the province calculated at basic prices rose by 4.6% in 2017 to $327.4 billion, which was the largest increase recorded in Canada, and it ended two consecutive years of decreases.[91]

Alberta's debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to peak at 12.1% in fiscal year 2021–2022, falling to 11.3% the following year.[92]

The Calgary-Edmonton Corridor is the most urbanized region in the province and one of the densest in Canada. The region covers a distance of roughly 400 km (250 mi) north to south. In 2001, the population of the Calgary-Edmonton Corridor was 2.15 million (72% of Alberta's population).[93] It is also one of the fastest-growing regions in the country. A 2003 study by TD Bank Financial Group found the corridor to be the only Canadian urban centre to amass a United States level of wealth while maintaining a Canadian style quality of life, offering universal health care benefits. The report found that GDP per capita in the corridor was 10% above average United States metropolitan areas and 40% above other Canadian cities at that time.[94]

The Fraser Institute states that Alberta also has very high levels of economic freedom and rates Alberta as the freest economy in Canada,[95] and second-freest economy amongst U.S. states and Canadian provinces.[96]

In 2014, merchandise exports totalled US$121.4 billion. Energy revenues totalled $111.7 billion and Energy resource exports totalled $90.8 billion. Farm Cash receipts from agricultural products totalled $12.9 billion. Shipments of forest products totalled $5.4 billion while exports were $2.7 billion. Manufacturing sales totalled $79.4 billion, and Alberta's information and communications technology (ICT) industries generated over $13 billion in revenue. In total, Alberta's 2014 GDP amassed $364.5 billion in 2007 dollars, or $414.3 billion in 2015 dollars. In 2015, Alberta's GDP grew unstably despite low oil prices, with growth rates as high 4.4% and as low as 0.2%.[97][98]

Agriculture and forestry

[edit]

Agriculture has a significant position in the province's economy. The province has over three million head of cattle,[99] and Alberta beef has a healthy worldwide market. Forty percent of all Canadian beef is produced in Alberta.[100] The province also produces the most bison meat in Canada.[101] Sheep for wool and mutton are also raised.[102]

Wheat and canola[103] are primary farm crops, with Alberta leading the provinces in spring wheat production; other grains are also prominent. Much of the farming is dryland farming, often with fallow seasons interspersed with cultivation. Continuous cropping (in which there is no fallow season) is gradually becoming a more common mode of production because of increased profits and a reduction of soil erosion. Across the province, the once common grain elevator is slowly being lost as rail lines are decreasing; farmers typically truck the grain to central points.[104]

Alberta is the leading beekeeping province of Canada, with some beekeepers wintering hives indoors in specially designed barns in southern Alberta, then migrating north during the summer into the Peace River valley where the season is short but the working days are long for honeybees to produce honey from clover and fireweed. Hybrid canola also requires bee pollination, and some beekeepers service this need.[105]

Forestry plays a vital role in Alberta's economy, providing over 15,000 jobs and contributing billions of dollars annually.[106] Uses for harvested timber include pulpwood, hardwood, engineered wood and bioproducts such as chemicals and biofuels.

Industry

[edit]Alberta is the largest producer of conventional crude oil, synthetic crude, natural gas and gas products in Canada. Alberta is the world's second-largest exporter of natural gas and the fourth-largest producer.[107] Two of the largest producers of petrochemicals in North America are in central and north-central Alberta. In both Red Deer and Edmonton, polyethylene and vinyl manufacturers produce products that are shipped all over the world. Edmonton's oil refineries provide the raw materials for a large petrochemical industry to the east of Edmonton.

The Athabasca oil sands surrounding Fort McMurray have estimated unconventional oil reserves approximately equal to the conventional oil reserves of the rest of the world, estimated to be 1.6×1012 barrels (250 km3).[108] Many companies employ both conventional strip mining and non-conventional in situ methods to extract the bitumen from the oil sands. As of late 2006, there were over $100 billion in oil sands projects under construction or in the planning stages in northeastern Alberta.[109]

Another factor determining the viability of oil extraction from the oil sands is the price of oil. The oil price increases since 2003 have made it profitable to extract this oil, which in the past would give little profit or even a loss. By mid-2014, rising costs and stabilizing oil prices threatened the economic viability of some projects. An example of this was the shelving of the Joslyn North project[110] in the Athabasca region in May 2014.[111]

With concerted effort and support from the provincial government, several high-tech industries have found their birth in Alberta, notably patents related to interactive liquid-crystal display systems.[112] With a growing economy, Alberta has several financial institutions dealing with civil and private funds.

Tourism

[edit]

Alberta has been a tourist destination from the early days of the 20th century, with attractions including outdoor locales for skiing, hiking, and camping, shopping locales such as West Edmonton Mall, Calgary Stampede, outdoor festivals, professional athletic events, international sporting competitions such as the Commonwealth Games and Olympic Games, as well as more eclectic attractions. According to Alberta Economic Development, Calgary and Edmonton both host over four million visitors annually. Banff, Jasper and the Rocky Mountains are visited by about three million people per year.[113] Alberta tourism relies heavily on Southern Ontario tourists, as well as tourists from other parts of Canada, the United States, and many other countries.

There are also natural attractions like Elk Island National Park, Wood Buffalo National Park, and the Columbia Icefield. Alberta's Rockies include well-known tourist destinations Banff National Park and Jasper National Park. The two mountain parks are connected by the scenic Icefields Parkway. Banff is located 128 km (80 mi) west of Calgary on Highway 1, and Jasper is located 366 km (227 mi) west of Edmonton on the Yellowhead Highway. Five of Canada's fourteen UNESCO World Heritage Sites are located within the province: Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks, Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, Wood Buffalo National Park, Dinosaur Provincial Park and Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. A number of these areas hold ski resorts, most notably Banff Sunshine, Lake Louise, Marmot Basin, Norquay and Nakiska.

About 1.2 million people visit the Calgary Stampede,[114] a celebration of Canada's own Wild West and the cattle ranching industry. About 700,000 people enjoy Edmonton's K-Days (formerly Klondike Days and Capital EX).[115][116] Edmonton was the gateway to the only all-Canadian route to the Yukon gold fields, and the only route which did not require gold-seekers to travel the exhausting and dangerous Chilkoot Pass.

Another tourist destination that draws more than 650,000 visitors each year is the Drumheller Valley, located northeast of Calgary. Drumheller, known as the "Dinosaur Capital of The World", offers the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology. Drumheller also had a rich mining history being one of Western Canada's largest coal producers during the war years. Another attraction in east-central Alberta is Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions, a popular tourist attraction operated out of Stettler, that offers train excursions into the prairie and caters to tens of thousands of visitors every year.

Government and politics

[edit]

The Government of Alberta is organized as a parliamentary democracy with a unicameral legislature. Its unicameral legislature—the Legislative Assembly—consists of 87 members elected first past the post (FPTP) from single-member constituencies.[117] Locally municipal governments and school boards are elected and operate separately. Their boundaries do not necessarily coincide.

As King of Canada, Charles III is the head of state of Alberta. His duties concerning the Government of Alberta are carried out by Lieutenant Governor Salma Lakhani.[118] The King and lieutenant governor are figureheads whose actions are highly restricted by custom and constitutional convention. The lieutenant governor handles numerous honorific duties in the name of the King. The government is headed by the premier. The premier is normally a member of the Legislative Assembly, and draws all the members of the Cabinet from among the members of the Legislative Assembly. The City of Edmonton is the seat of the provincial government—the capital of Alberta. The current premier is Danielle Smith, who was sworn in on October 11, 2022.

Alberta's elections have tended to yield much more conservative outcomes than those of other Canadian provinces. From the 1980s to the 2010s, Alberta had three main political parties, the Progressive Conservatives ("Conservatives" or "Tories"), the Liberals, and the social democratic New Democrats. The Wildrose Party, a more libertarian party formed in early 2008, gained much support in the 2012 election and became the official opposition, a role it held until 2017 when it was dissolved and succeeded by the new United Conservative Party created by the merger of Wildrose and the Progressive Conservatives. The strongly conservative Social Credit Party was a power in Alberta for many decades, but fell from the political map after the Progressive Conservatives came to power in 1971.

For 44 years the Progressive Conservatives governed Alberta. They lost the 2015 election to the NDP (which formed their own government for the first time in provincial history, breaking almost 80 consecutive years of right-wing rule),[119] suggesting at the time a possible shift to the left in the province, also indicated by the election of progressive mayors in both of Alberta's major cities.[120] Since becoming a province in 1905, Alberta has seen only five changes of government—only six parties have governed Alberta: the Liberals, from 1905 to 1921; the United Farmers of Alberta, from 1921 to 1935; the Social Credit Party, from 1935 to 1971; the Progressive Conservative Party, from 1971 to 2015; from 2015 to 2019, the Alberta New Democratic Party; and from 2019, the United Conservative Party, with the most recent transfer of power being the first time in provincial history that an incumbent government was not returned to a second term.

Administrative divisions

[edit]The province is divided into ten types of local governments – urban municipalities (including cities, towns, villages and summer villages), specialized municipalities, rural municipalities (including municipal districts (often named as counties), improvement districts, and special areas), Métis settlements, and Indian reserves. All types of municipalities are governed by local residents and were incorporated under various provincial acts, with the exception of improvement districts (governed by either the provincial or federal government), and Indian reserves (governed by local band governments under federal jurisdiction).

Law enforcement

[edit]

Policing in the province of Alberta upon its creation was the responsibility of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police. In 1917, due to pressures of the First World War, the Alberta Provincial Police was created. This organization policed the province until it was disbanded as a Great Depression-era cost-cutting measure in 1932. It was at that time the, now renamed, Royal Canadian Mounted Police resumed policing of the province, specifically RCMP "K" Division. With the advent of the Alberta Sheriffs Branch, the distribution of duties of law enforcement in Alberta has been evolving as certain aspects, such as traffic enforcement, mobile surveillance and the close protection of the Premier of Alberta have been transferred to the Sheriffs. In 2006, Alberta formed the Alberta Law Enforcement Response Teams (ALERT) to combat organized crime and the serious offences that accompany it. ALERT is made up of members of the RCMP, Sheriffs Branch, and various major municipal police forces in Alberta.

Military

[edit]Military bases in Alberta include Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Cold Lake, CFB Edmonton, CFB Suffield and CFB Wainwright. Air force units stationed at CFB Cold Lake have access to the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range.[121] CFB Edmonton is the headquarters for the 3rd Canadian Division.[122] CFB Suffield hosts British troops and is the largest training facility in Canada.[123]

Taxation

[edit]According to Alberta's 2009 budget, government revenue in that year came mainly from royalties on non-renewable natural resources (30.4%), personal income taxes (22.3%), corporate and other taxes (19.6%), and grants from the federal government primarily for infrastructure projects (9.8%).[124] In 2014, Alberta received $6.1 billion in bitumen royalties. With the drop in the price of oil in 2015 it was down to $1.4 billion. In 2016, Alberta received "about $837 million in royalty payments from oil sands Royalty Projects".[125] According to the 2018–2021 fiscal plan, the two top sources of revenue in 2016 were personal income tax at $10,763 million and federal transfers of $7,976 million with total resource revenue at $3,097 million.[126]: 45 Alberta is the only province in Canada without a provincial sales tax. Alberta residents are subject to the federal sales tax, the Goods and Services Tax of 5%.

| Revenue source | in millions of dollars[126] |

| personal income tax | 10,763 |

| federal transfers | 7,976 |

| Other tax revenue | 5,649 |

| Corporate income tax | 3,769 |

| Premiums, fees and licenses | 3,701 |

| Investment income | 3,698 |

| Resource revenue – other | 1,614 |

| Resource revenue – Bitumen royalties | 1,483 |

| Net income from business enterprises | 543 |

| Total revenue | 42,293 |

From 2001 to 2016, Alberta was the only Canadian province to have a flat tax of 10% of taxable income, which was introduced by Premier, Ralph Klein, as part of the Alberta Tax Advantage, which also included a zero-percent tax on income below a "generous personal exemption".[127][128]

In 2016, under Premier Rachel Notley, while most Albertans continued to pay the 10% income tax rate, new tax brackets 12%, 14%, and 15% for those with higher incomes ($128,145 annually or more) were introduced.[129][127] Alberta's personal income tax system maintained a progressive character by continuing to grant residents personal tax exemptions of $18,451,[130] in addition to a variety of tax deductions for persons with disabilities, students, and the aged.[131] Alberta's municipalities and school jurisdictions have their own governments who usually work in co-operation with the provincial government. By 2018, most Albertans continued to pay the 10% income tax rate.[129]

According to a March 2015 Statistics Canada report, the median household income in Alberta in 2014 was about $100,000, which is 23% higher than the Canadian national average.[132]

Based on Statistic Canada reports, low-income Albertans, who earn less than $25,000 and those in the high-income bracket earning $150,000 or more, are the lowest-taxed people in Canada.[129] Those in the middle income brackets representing those that earn about $25,000 to $75,000[Notes 1] pay more in provincial taxes than residents in British Columbia and Ontario.[129] In terms of income tax, Alberta is the "best province" for those with a low income because there is no provincial income tax for those who earn $18,915 or less.[129] Even with the 2016 progressive tax brackets up to 15%, Albertans who have the highest incomes, those with a $150,000 annual income or more—about 178,000 people in 2015, pay the least in taxes in Canada.[129] — About 1.9 million Albertans earned between $25,000 and $150,000 in 2015.[129]

Alberta also privatized alcohol distribution. By 2010, privatization had increased outlets from 304 stores to 1,726; 1,300 jobs to 4,000 jobs; and 3,325 products to 16,495 products.[133] Tax revenue also increased from $400 million to $700 million.

In 2017/18 Alberta collected about $2.4 billion in education property taxes from municipalities.[134] Alberta municipalities raise a significant portion of their income through levying property taxes.[135] The value of assessed property in Alberta was approximately $727 billion in 2011.[136] Most real property is assessed according to its market value.[135] The exceptions to market value assessment are farmland, railways, machinery and equipment and linear property, all of which is assessed by regulated rates.[137] Depending on the property type, property owners may appeal a property assessment to their municipal 'Local Assessment Review Board', 'Composite Assessment Review Board,' or the Alberta Municipal Government Board.[135][138]

Culture

[edit]

Calgary is famous for its Stampede, dubbed "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth". The Stampede is Canada's biggest rodeo festival and features various races and competitions, such as calf roping and bull riding. In line with the western tradition of rodeo are the cultural artisans that reside and create unique Alberta western heritage crafts.

Summer brings many festivals to Alberta, especially in Edmonton. The Edmonton Fringe Festival is the world's second-largest after the Edinburgh Festival. Both Calgary and Edmonton host many annual festivals and events, including folk music festivals. The city's "heritage days" festival sees the participation of over 70 ethnic groups. Edmonton's Churchill Square is home to a large number of the festivals, including A Taste of Edmonton and The Works Art & Design Festival throughout the summer months.

In 2019, Minister of Culture and Tourism Ricardo Miranda announced the Alberta Artist in Residence program in conjunction with the province's first Month of the Artist[139] to celebrate the arts and the value they bring to the province, both socially and economically,[140] The artist is selected each year via a public and competitive process is expected to do community outreach and attend events to promote the arts throughout the province. The award comes with $60,000 funding which includes travel and materials costs.[141] On January 31, 2019, Lauren Crazybull was named Alberta's first artist in residence.[142][143][141] Alberta is the first province to launch an artist in residence program in Canada.

Sports

[edit]Education

[edit]As with any Canadian province, the Alberta Legislature has (almost) exclusive authority to make laws respecting education. Since 1905, the Legislature has used this capacity to continue the model of locally elected public and separate school boards which originated prior to 1905, as well as to create and regulate universities, colleges, technical institutions, and other educational forms and institutions (public charter schools, private schools, homeschooling).

Elementary and secondary

[edit]There are forty-two public school jurisdictions in Alberta, and seventeen operating separate school jurisdictions. Sixteen of the operating separate school jurisdictions have a Catholic electorate, and one (St. Albert) has a Protestant electorate. In addition, one Protestant separate school district, Glen Avon, survives as a ward of the St. Paul Education Region. The City of Lloydminster straddles the Albertan/Saskatchewan border, and both the public and separate school systems in that city are counted in the above numbers: both of them operate according to Saskatchewan law.

For many years, the provincial government has funded the greater part of the cost of providing K–12 education. Prior to 1994, public and separate school boards in Alberta had the legislative authority to levy a local tax on property as supplementary support for local education. In 1994, the government of the province eliminated this right for public school boards, but not for separate school boards. Since 1994, there has continued to be a tax on property in support of K–12 education; the difference is that the provincial government now sets the mill rate, the money is collected by the local municipal authority and remitted to the provincial government. The relevant legislation requires that all the money raised by this property tax must go to support K–12 education provided by school boards. The provincial government pools the property tax funds from across the province and distributes them, according to a formula, to public and separate school jurisdictions and Francophone authorities.

Public and separate school boards, charter schools, and private schools all follow the Program of Studies and the curriculum approved by the provincial department of education (Alberta Education). Homeschool tutors may choose to follow the Program of Studies or develop their own Program of Studies. Public and separate schools, charter schools, and approved private schools all employ teachers who are certificated by Alberta Education, they administer Provincial Achievement Tests and Diploma Examinations set by Alberta Education, and they may grant high school graduation certificates endorsed by Alberta Education.

Post-secondary

[edit]

Several publicly funded post-secondary institutions are governed under the province's Post-secondary Learning Act. This includes four comprehensive research universities that provides undergraduate and graduate degrees, Athabasca University, the University of Alberta, the University of Calgary, and the University of Lethbridge; and three undergraduate universities that primarily provide bachelor's degrees, the Alberta University of the Arts, Grant MacEwan University, and Mount Royal University.[144]

Nine comprehensive community colleges offer primarily offer diploma and certificate programs, Bow Valley College, Keyano College, Lakeland College, Lethbridge College, Medicine Hat College, NorQuest College, Northern Lakes College, Olds College, and Portage College. In addition, there are also four polytechnic institutes that provide specific career training and provides apprenticeships and diplomas, the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology, the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, Northwestern Polytechnic, and Red Deer Polytechnic. The Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity is a specialized arts and cultural institution that is also empowered to provide diploma programs under the Post-secondary Learning Act.[144]

Alberta is also home to five independent postsecondary institutions that provide diplomas/degrees for approved programming, Ambrose University, Burman University, Concordia University of Edmonton, The King's University, and St. Mary's University. Although the five institutions operate under their own legislation, they remain partly governed by the province's Post-secondary Learning Act.[144] In addition to these institutions, there are also 190 private career colleges in Alberta.[145]

There was some controversy in 2005 over the rising cost of post-secondary education for students (as opposed to taxpayers). In 2005, Premier Ralph Klein made a promise that he would freeze tuition and look into ways of reducing schooling costs.[146][147][needs update]

Health care

[edit]Alberta provides a publicly funded, fully integrated health system, through Alberta Health Services (AHS)—a quasi-independent agency that delivers health care on behalf of the Government of Alberta's Ministry of Health.[148] The Alberta government provides health services for all its residents as set out by the provisions of the Canada Health Act of 1984. Alberta became Canada's second province (after Saskatchewan) to adopt a Tommy Douglas-style program in 1950, a precursor to the modern medicare system.

Alberta's health care budget was $22.5 billion during the 2018–2019 fiscal year (approximately 45% of all government spending), making it the best-funded health-care system per-capita in Canada.[149] Every hour the province spends more than $2.5 million, (or $60 million per day), to maintain and improve health care in the province.[150]

Notable health, education, research, and resources facilities in Alberta, all of which are located within Calgary or Edmonton. Health centres in Calgary include:

- Alberta Children's Hospital

- Foothills Medical Centre

- Grace Women's Health Centre

- Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta

- Peter Lougheed Centre

- Rockyview General Hospital

- South Health Campus

- Tom Baker Cancer Centre

- University of Calgary Medical Centre (UCMC)

Health centres in Edmonton include:

- Alberta Diabetes Institute

- Cross Cancer Institute

- Edmonton Clinic

- Grey Nuns Community Hospital

- Lois Hole Hospital for Women

- Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute

- Misericordia Community Hospital

- Rexall Centre for Pharmacy and Health Research

- Royal Alexandra Hospital

- Stollery Children's Hospital

- University of Alberta Hospital

The Edmonton Clinic complex, completed in 2012, provides a similar research, education, and care environment as the Mayo Clinic in the United States.[151][152]

All public health care services funded by the Government of Alberta are delivered operationally by Alberta Health Services. AHS is the province's single health authority, established on July 1, 2008, which replaced nine regional health authorities. AHS also funds all ground ambulance services in the province, as well as the province-wide Shock Trauma Air Rescue Service (STARS) air ambulance service.[153]

Transportation

[edit]Air

[edit]

Alberta is well-connected by air, with international airports in both Calgary and Edmonton. Calgary International Airport and Edmonton International Airport are the fourth- and fifth-busiest in Canada, respectively. Calgary's airport is a hub for WestJet Airlines and a regional hub for Air Canada, primarily serving the prairie provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) for connecting flights to British Columbia, eastern Canada, fifteen major United States centres, nine European airports, one Asian airport and four destinations in Mexico and the Caribbean.[154] Edmonton's airport acts as a hub for the Canadian north and has connections to all major Canadian airports as well as airports in the United States, Europe, Mexico, and the Caribbean .[155]

Public transit

[edit]Calgary, Edmonton, Red Deer, Medicine Hat, and Lethbridge have substantial public transit systems. In addition to buses, Calgary and Edmonton operate light rail transit (LRT) systems. Edmonton LRT, which is underground in the downtown core and on the surface outside the downtown core was the first of the modern generation of light rail systems to be built in North America, while the Calgary CTrain has one of the highest numbers of daily riders of any LRT system in North America.

Rail

[edit]

There are more than 9,000 km (5,600 mi) of operating mainline railway in Alberta. The vast majority of this trackage is owned by the Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC) and Canadian National Railway (CN) companies, which operate freight transport across the province. Additional railfreight service in the province is provided by two shortline railways: the Battle River Railway and Forty Mile Rail.

Passenger trains include Via Rail's Canadian (Toronto–Vancouver) and Jasper–Prince Rupert trains, which use the CN mainline and pass through Jasper National Park and parallel the Yellowhead Highway during at least part of their routes. The Rocky Mountaineer operates two sections: one from Vancouver to Banff over CP tracks, and a section that travels over CN tracks to Jasper.

Alberta's premier, Danielle Smith has also confirmed a 15-year master plan to expand passenger rail into Alberta.[156] This plan is set to provide rail services to Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, Banff, Grand Prairie, Fort McMurray, and most importantly an intercity rail service between Edmonton and Calgary, as well as a commuter rail systems in the respective cities. Groundbreaking is set to start in 2027, according to Transportation Minister Devin Dreeshen.

Road

[edit]Alberta has over 473,000 km (294,000 mi) of highways and roads in its road network.[157] The main north–south corridor is Highway 2, which begins south of Cardston at the Carway border crossing and is part of the CANAMEX Corridor. Beginning at the Coutts border crossing and ending at Lethbridge, Highway 4, effectively extends Interstate 15 into Alberta and is the busiest United States gateway to the province. Highway 3 joins Lethbridge to Fort Macleod and links Highway 2 to Highway 4. Highway 2 travels north through Fort Macleod, Calgary, Red Deer, and Edmonton.[158]

North of Edmonton, the highway continues to Athabasca, then northwesterly along the south shore of Lesser Slave Lake into High Prairie, north to Peace River, west to Fairview and finally south to Grande Prairie, where it ends at an interchange with Highway 43.[158] The section of Highway 2 between Calgary and Edmonton has been named the Queen Elizabeth II Highway to commemorate the visit of the monarch in 2005.[159] Highway 2 is supplemented by two more highways that run parallel to it: Highway 22, west of Highway 2, known as Cowboy Trail, and Highway 21, east of Highway 2. Highway 43 travels northwest into Grande Prairie and the Peace River Country. Travelling northeast from Edmonton, the Highway 63 connects to Fort McMurrayand the Athabasca oil sands.[158]

Alberta has two main east–west corridors. The southern corridor, part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, enters the province near Medicine Hat, runs westward through Calgary, and leaves Alberta through Banff National Park. The northern corridor, also part of the Trans-Canada network and known as the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16), runs west from Lloydminster in eastern Alberta, through Edmonton and Jasper National Park into British Columbia.[158] One of the most scenic drives is along the Icefields Parkway, which runs for 228 km (142 mi) between Jasper and Lake Louise, with mountain ranges and glaciers on either side of its entire length. A third corridor stretches across southern Alberta; Highway 3 runs between Crowsnest Pass and Medicine Hat through Lethbridge and forms the eastern portion of the Crowsnest Highway.[158] Another major corridor through central Alberta is Highway 11 (also known as the David Thompson Highway), which runs east from the Saskatchewan River Crossing in Banff National Park through Rocky Mountain House and Red Deer, connecting with Highway 12, 20 km (12 mi) west of Stettler. The highway connects many of the smaller towns in central Alberta with Calgary and Edmonton, as it crosses Highway 2 just west of Red Deer.[158]

Urban stretches of Alberta's major highways and freeways are often called trails. For example, Highway 2, the main north–south highway in the province, is called Deerfoot Trail as it passes through Calgary but becomes Calgary Trail (southbound) and Gateway Boulevard (northbound) as it enters Edmonton and then turns into St. Albert Trail as it leaves Edmonton for the City of St. Albert. Calgary, in particular, has a tradition of calling its largest urban expressways trails and naming many of them after prominent First Nations individuals and tribes, such as Crowchild Trail, Deerfoot Trail, and Stoney Trail.[160]

Friendship partners

[edit]Alberta has relationships with many provinces, states, and other entities worldwide.[161]

- Gangwon-do, South Korea (1974)[162]

- Hokkaido, Japan (1980)

- Heilongjiang, China (1981)

- Montana, United States (1985)

- Tyumen, Russia (1992)

- Khanty–Mansi, Russia (1995)

- Yamalo-Nenets, Russia (1997)

- Jalisco, Mexico (1999)

- Alaska, United States (2002)

- Saxony, Germany (2002)

- Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine (2004)

- Lviv, Ukraine (2005)

- California, United States (1997)[163]

- Guangdong, China (2017)

See also

[edit]- Index of Alberta-related articles

- Outline of Alberta

- Royal eponyms in Canada

- Edmonton

- Calgary

- Banff National Park

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to a 2018 CBC article, Albertans whose annual income is less than $25,000 pay the least income tax in Canada; those that earn about $50,000 "pay more than both Ontarians and British Columbians". Residents of British Columbia who earn about $75,000 pay $1,200 less in provincial taxes than those in Alberta. Albertans who earn about $100,000, "pay less than Ontarians but still more than people in B.C." Alberta taxpayers who earn $250,000 a year or more, pay $4,000 less in provincial taxes than someone with a similar income in B.C. and "about $18,000 less than in Quebec."

References

[edit]- ^ "Alberta". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ a b c "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Data table". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Population estimates, quarterly". Statistics Canada. September 27, 2023. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "Languages Act". Government of Alberta. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Dupuis, Serge (February 5, 2020). "Francophones of Alberta (Franco-Albertains)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

In 1988, as a reaction to the Supreme Court's Mercure case, Alberta passed the Alberta Languages Act, making English the province's official language and repealing the language rights enjoyed under the North-West Territories Act, while allowing French in the Legislative Assembly and court.

- ^ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, provincial and territorial, annual". Statistics Canada. November 8, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI". Global Data Lab. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Get to know Canada - Provinces and territories". aem. April 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Wenckstern, Erin (January 8, 2015). "Chinook winds and Alberta weather". The Weather Network. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ Harrison, Raymond O. "Alberta - Climate". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "The 10 Biggest Cities In Alberta". WorldAtlas. September 9, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 7, 2018. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Census 2016 Language of Albertans" Archived December 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (consulted April 2021)

- ^ "Key Sectors". investalberta.ca. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Leduc Era: 1947 to 1970s - Conventional Oil - Alberta's Energy Heritage". history.alberta.ca. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "Economic Dashboard - Gross Domestic Product". economicdashboard.alberta.ca. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ "Dictionary, Census of Population, 2016 - Market income". Statistics Canada. May 3, 2017. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "History & Geology". Bow Valley Naturalists. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "Alberta becomes a Province". Alberta Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ "World Heritage Sites in Alberta". www.albertaparks.ca. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "History". Government of Alberta. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ "A land of freedom and beauty, named for love". Government of Alberta. 2002. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ^ Larry Donovan; Tom Monto (2006). Alberta Place Names: The Fascinating People & Stories Behind the Naming of Alberta. Dragon Hill Publishing Ltd. p. 121. ISBN 1-896124-11-9.

- ^ Campbell, Mike. "Meaning, origin and history of the name Albert". Behind the Name. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ "Alberta | Origin and meaning of the name Alberta by Online Etymology Dictionary". etymonline.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ "Land and freshwater area, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. February 2005. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ^ "Alberta, Canada". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Climate and Geography" (PDF). About Alberta. Government of Alberta. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ^ "Athabasca River". The Canadian Heritage Rivers System. 2011. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "PEACE RIVER AT PEACE POINT". www.r-arcticnet.sr.unh.edu. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "Atlas of Alberta Railways Maps – Alberta Land Grants". ualberta.ca. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ "Alberta". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Foundation of Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ "Alberta Weather and Climate Data". Government of Alberta, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. 2012. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Climate of Alberta". Agroclimatic Atlas of Alberta. Government of Alberta. 2003. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ "Alberta Clipper". The Weather Notebook. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ "Chance of White Christmas". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on March 1, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Vettese, Dayna (September 4, 2014). "Tornadoes in Canada: Everything you need to know". The Weather Network. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Canadian Climate Normals". Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Plant Hardiness Zone by Municipality". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- ^ Prairie Crocus Information Archived May 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Alberta Plant Watch. Author Annora Brown. Published: no date given. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Neil L. Jennings (2010). In Plain Sight: Exploring the Natural Wonders of Southern Alberta. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-897522-78-3. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Bradford Angier (1974). Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Stackpole Books. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-8117-2018-2. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ Paul A. Johnsgard (2005). Prairie Dog Empire: A Saga of the Shortgrass Prairie. U of Nebraska Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8032-2604-3. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ "The History of Rat Control in Alberta". Alberta Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ^ Markusoff, Jason (September 1, 2009). "Rodents defying Alberta's rat-free claim". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ "Alberta's rat-free status in jeopardy: More than dozen found in landfill". The Globe and Mail. August 15, 2012. Archived from the original on August 17, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ "Several rats found at Medicine Hat landfill, one spotted at nearby farm". CBC News. April 8, 2014. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2012.