Battle of the Yarmuk

| Battle of Yarmuk | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim conquest of the Levant (Arab–Byzantine wars) | |||||||||

Illustration of the Battle of Yarmuk by an anonymous Catalan illustrator (c. 1310 – 1325) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate |

Byzantine Empire Ghassanid Kingdom Tanukhids | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Umar ibn al-Khattab Khalid ibn al-Walid Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah Amr ibn al-As Zubayr ibn al-Awwam Malik al-Ashtar Shurahbil ibn Hasana Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan Al-Qa'qa' ibn 'Amr al-Tamimi Amru bin Ma'adi Yakrib Iyad ibn Ghanm Dhiraar bin Al-Azwar Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Bakr Ubadah ibn al-Samit |

Heraclius Theodore Trithyrius † Vahan †[g] Jabalah ibn al-Aiham Dairjan † Niketas the Persian Buccinator (Qanatir) Gregory[1] | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

15,000–40,000 (modern estimates)[d] 24,000–40,000 (primary Arab sources)[e] |

20,000–40,000 (modern estimates)[a] 100,000–200,000 (primary Arab sources)[c] 140,000 (primary Roman sources)[b] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 4,000 killed[2] |

40,000 (modern estimates)[3] 70,000–120,000 killed (primary Arab sources)[f] | ||||||||

Battle location on a map of modern Syria | |||||||||

The Battle of the Yarmuk (also spelled Yarmouk) was a major battle between the army of the Byzantine Empire and the Arab Muslim forces of the Rashidun Caliphate. The battle consisted of a series of engagements that lasted for six days in August 636, near the Yarmouk River (also called the Hieromyces River), along what are now the borders of Syria–Jordan and Syria-Israel, southeast of the Sea of Galilee. The result of the battle was a decisive Muslim victory that ended Roman rule in Syria after about seven centuries. The Battle of the Yarmuk is regarded as one of the most decisive battles in military history,[4][5] and it marked the first great wave of early Muslim conquests after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, heralding the rapid advance of Islam into the then-Christian/Roman Levant.

To check the Arab advance and to recover lost territory, Emperor Heraclius had sent a massive expedition to the Levant in May 636. As the Byzantine army approached, the Arabs tactically withdrew from Syria and regrouped all their forces at the Yarmuk plains close to the Arabian Peninsula, where they were reinforced, and defeated the numerically superior Byzantine army. The battle is widely regarded to be Khalid ibn al-Walid's greatest military victory and to have cemented his reputation as one of the greatest tacticians and cavalry commanders in history.[6]

Background

[edit]In 610, during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, Heraclius became the emperor of the Byzantine Empire,[7] after overthrowing Phocas. Meanwhile, the Sasanian Empire conquered Mesopotamia and in 611 they overran Syria and entered Anatolia, occupying Caesarea Mazaca (now Kayseri, Turkey). In 612, Heraclius managed to expel the Persians from Anatolia but was decisively defeated in 613 when he launched a major offensive in Syria against the Persians.[8] Over the following decade, the Persians were able to conquer Palestine and Egypt. Meanwhile, Heraclius prepared for a counterattack and rebuilt his army.

In 622, Heraclius finally launched his offensive.[9] After his overwhelming victories over the Persians and their allies in the Caucasus and Armenia, Heraclius launched a winter offensive against the Persians in Mesopotamia in 627, winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Nineveh, thus threatening the Persian capital city of Ctesiphon. Discredited by the series of disasters, Khosrow II was overthrown and killed in a coup led by his son Kavad II,[10] who immediately sued for peace and agreed to withdraw from all occupied territories of the Byzantine Empire. Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem with a majestic ceremony in 629.[11]

Meanwhile, there had been rapid political development in the Arabian Peninsula, where Muhammad had been preaching Islam and, by 630, had successfully annexed most of Arabia under a single political authority. When Muhammad died in June 632, Abu Bakr was chosen as caliph and his political successor. Troubles emerged soon after Abu Bakr's succession, and several Arab tribes openly revolted against him. He declared war against the rebels. In what became known as the Ridda wars of 632–633, Abu Bakr managed to defeat his opponents and unite Arabia under the central authority of the caliph at Medina.[12]

Once the rebels had been subdued, Abu Bakr began a war of conquest, beginning with Iraq. His most brilliant general, Khalid ibn al-Walid, conquered Iraq in a series of successful campaigns against the Sassanid Persians. Abu Bakr's confidence grew, and once Khalid had established his stronghold in Iraq, Abu Bakr issued a call to arms for the invasion of Syria in February 634.[13] The Muslim invasion of Syria was a series of carefully planned and well-co-ordinated military operations, which employed strategy, instead of pure strength, to deal with the Byzantine defensive measures.[14]

The Muslim armies, however, soon proved to be too small to handle the Byzantine response, and their commanders called for reinforcements. Khalid was sent by Abu Bakr from Iraq to Syria with reinforcements and to lead the invasion. In July, the Byzantines were decisively defeated at Ajnadayn. Damascus fell in September, followed by the Battle of Fahl, in which the last significant garrison of Palestine was routed.[15]

After Abu Bakr died in 634, his successor, Umar, was determined to continue the Caliphate's expansion deeper into Syria.[16] Though previous campaigns led by Khalid had been successful, he was replaced by Abu Ubaidah. Having secured southern Palestine, Muslim forces now advanced up the trade route, and Tiberias and Baalbek fell without much struggle and conquered Emesa early in 636. The Muslims then continued their conquest across the Levant.[17]

Byzantine counterattack

[edit]Having seized Emesa, the Muslims were just a march away from Aleppo, a Byzantine stronghold, and Antioch, where Heraclius resided. Seriously alarmed by the series of setbacks, Heraclius prepared for a counterattack to reacquire the lost regions.[18][19] In 635 Yazdegerd III, the Emperor of Persia, sought an alliance with the Byzantine Emperor. Heraclius married off his daughter (according to traditions, his granddaughter) Manyanh to Yazdegerd III, to cement the alliance. While Heraclius prepared for a major offensive in the Levant, Yazdegerd was to mount a simultaneous counterattack in Iraq, in what was meant to be a well-coordinated effort. When Heraclius launched his offensive in May 636, Yazdegerd could not co-ordinate with the maneuver, probably owing to the exhausted condition of his government, and what would have been a decisive plan missed the mark.[20]

Byzantine preparations began in late 635 and by May 636 Heraclius had a large force concentrated at Antioch in Northern Syria.[21] The assembled Byzantine army contingents consisted of Slavs, Franks, Georgians, Armenians, Christian Arabs, Lombards, Avars, Khazars, Balkans and Göktürks.[22] The force was organized into five armies, the joint leader of which was Theodore Trithyrius. Vahan, an Armenian and the former garrison commander of Emesa,[23] was made the overall field commander,[24] and had under his command a purely Armenian army. Buccinator (Qanatir), a Slavic prince, commanded the Slavs and Jabalah ibn al-Aiham, king of the Ghassanid Arabs, commanded an exclusively Christian Arab force. The remaining contingents, all European, were placed under Gregory and Dairjan.[25][26] Heraclius himself supervised the operation from Antioch. Byzantine sources mention Niketas, son of the Persian general Shahrbaraz, among the commanders, but it is not certain which army he commanded.[27]

The Rashidun army was then split into four groups: one under Amr in Palestine, one under Shurahbil in Jordan, one under Yazid in the Damascus-Caesarea region and the last one under Abu Ubaidah along with Khalid at Emesa.

As the Muslim forces were geographically divided, Heraclius sought to exploit that situation and planned to attack. He did not wish to engage in a single pitched battle but rather to employ central position and fight the enemy in detail by concentrating large forces against each of the Muslim corps before they could consolidate their troops. By forcing the Muslims to retreat, or by destroying Muslim forces separately, he would fulfil his strategy of recapturing lost territory. Reinforcements were sent to Caesarea under Heraclius' son Constantine III, probably to tie down Yazid's forces, which were besieging the town.[25] The Byzantine imperial army moved out from Antioch and Northern Syria in the middle of June 636.

The Byzantine imperial army was to operate under the following plan:

- Jabalah's lightly armed Christian Arabs would march to Emesa from Aleppo via Hama and hold the main Muslim army at Emesa.

- Dairjan would make a flanking movement between the coast and Aleppo's road and approach Emesa from the west, striking at the Muslims' left flank while they were being held frontally by Jabalah.

- Gregory would strike the Muslims' right flank, approaching Emesa from the northeast via Mesopotamia.

- Qanatir would march along the coastal route and occupy Beirut, from where he was to attack the weakly defended Damascus from the west to cut off the main Muslim army at Emesa.

- Vahan's corps would act as a reserve and would approach Emesa via Hama.[28]

Rashidun strategy

[edit]The Muslims discovered Heraclius' preparations at Shaizar from Byzantine prisoners. Alert to the possibility of being caught with separated forces that could be destroyed, Khalid called a council of war and advised Abu Ubaidah to pull the troops back from Palestine and Northern and Central Syria and concentrate the entire Rashidun army in one place.[29][30] Abu Ubaidah ordered the concentration of troops in the vast plain near Jabiyah, as control of the area made cavalry charges possible and facilitated the arrival of reinforcements from Umar, so that a strong, united force could be fielded against the Byzantine armies.[31] The position also benefited from close proximity to the Rashidun stronghold of Najd, if retreat became necessary. Instructions were also issued to return jizya (tribute) to people who had paid it.[32]

However, once concentrated at Jabiyah, the Muslims were subject to raids from pro-Byzantine Ghassanid forces. Encamping in the region was also precarious as a strong Byzantine force was garrisoned in Caeseara and could attack the Muslim rear while they were held in front by the Byzantine army. On Khalid's advice the Muslim forces retreated to Dara'ah (or Dara) and Dayr Ayyub, covering the gap between the Yarmuk Gorges and the Harra lava plains,[29] and established a line of camps in the eastern part of the plain of Yarmuk. This was a strong defensive position, and the maneuverers brought the Muslims and Byzantines into a decisive battle, which the latter had tried to avoid.[33] During the maneuvers, there were no engagements except for a minor skirmish between Khalid's elite light cavalry and the Byzantine advance guard.[34]

Battlefield

[edit]

The battlefield lies in the plain of Jordanian Hauran, just southeast of the Golan Heights, an upland region currently on the frontier between Jordan and Syria, east of the Sea of Galilee. The battle was fought on the plain east of Raqqat stream ravine. That ravine joins the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan River, on its south. The stream had very steep banks, ranging from 30 m (98 ft)–200 m (660 ft) in height. On the north is the Jabiyah road and to the east are the Azra hills although the hills were outside the actual field of battle. Strategically, there was only one prominence in the battlefield: a 100 m (330 ft) elevation known as Tel al Jumm'a, and for the Muslim troops concentrated there, the hill gave a good view of the plain of Yarmuk. The ravine on the west of the battlefield was accessible at a few places in 636 AD, and had one main crossing: a Roman bridge (Jisr-ur-Ruqqad) near Ain Dhakar[35][36] Logistically, the Yarmuk plain had enough water supplies and pastures to sustain both armies. The plain was excellent for cavalry maneuvers.[37][38]

Troop deployment

[edit]Most early accounts place the size of the Muslim forces between 36,000 and 40,000 and the number of Byzantine forces between 60,000 and 70,000 (This number has been estimated by taking into account the logistical situation of the Empire and with the view that they could never have mustered such troops when the Empire was at its apex but especially not with the especially weak and exhausted realm of 628 onwards). Modern estimates for the sizes of the respective armies vary: some estimates for the Byzantine army are around 40,000 at most,[39] while other estimates are 15,000 to 20,000.[40] Estimates for the Rashidun army are between 15,000 and 40,000,[41] most likely around 36,000.[39] Original accounts are mostly from Arab sources, generally agreeing that the Byzantine army and their allies outnumbered the Muslim Arabs by a 2 to 1.[m] The only early Byzantine source is Theophanes, who wrote a century later. Accounts of the battle vary, some stating it lasted a day, others six days.[41]

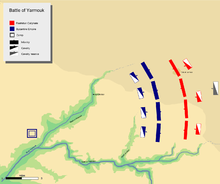

Rashidun army

[edit]During a council of war, the command of the Muslim army was transferred to Khalid[i] by Abu Ubaidah, Commander in Chief of the Muslim army.[42] After taking command, Khalid reorganized the army into 36 infantry regiments and four cavalry regiments, with his cavalry elite, the mobile guard, held in reserve. The army was organised in the Tabi'a formation, a tight, defensive infantry formation.[43] The army was lined up on a front of 12 kilometres (7.5 mi), facing west, with its left flank lying south on the Yarmuk River a mile before the ravines of Wadi al Allan began. The army's right flank was on the Jabiyah road in the north across the heights of Tel al Jumm'a,[44] with substantial gaps between the divisions so that their frontage would match that of the Byzantine battle line at 13 kilometres (8.1 mi). The centre of the army was under the command of Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah (left centre) and Shurahbil bin Hasana (right centre). The left wing was under the command of Yazid and the right wing was under Amr ibn al-A's.[42]

The centre, left and right wings were given cavalry regiments, to be used as a reserve for a counterattack if they were pushed back by the Byzantines. Behind the centre stood the mobile guard under the personal command of Khalid. If Khalid was too occupied in leading the general army, Dharar ibn al-Azwar would command the mobile guard. Over the course of the battle, Khalid would repeatedly make critical and decisive use of that mounted reserve.[42]

Khalid sent out several scouts to keep the Byzantines under observation.[45] In late July, Vahan sent Jabalah with his lightly armoured Christian-Arab forces to reconnoitre-in-force, but they were repulsed by the mobile guard. After the skirmish, no engagement occurred for a month.[46]

Weaponry

[edit]Helmets used included gilded helmets similar to the silver helmets of the Sassanid empire. Mail was commonly used to protect the face, neck, and cheeks as an aventail from the helmet or as a mail coif. Heavy leather sandals, as well as Roman-type sandal boots, were also typical of the early Muslim soldiers.[47] Armour included hardened leather scale or lamellar armour and mail armour. Infantry soldiers were more heavily armoured than horsemen. Large wooden or wickerwork shields were used. Long-shafted spears were used, with infantry spears being 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long and cavalry spears being up to 5.5 m (18 ft) long. Short infantry swords like the Roman gladius and Sassanid long swords were used; long swords were usually carried by horsemen. Swords were hung in baldrics. Bows were about 2 metres (6.6 ft) long when unbraced, similar in size to the famous English longbow. The maximum useful range of the traditional Arabian bow was about 150 m (490 ft). Early Muslim archers, while being infantry archers without the mobility of horseback archer regiments, proved to be very effective in defending against light and unarmoured cavalry attacks.[48]

Byzantine army

[edit]A few days after the Muslims encamped at the Yarmuk plain, the Byzantine army, preceded by the lightly armed Ghassanids of Jabalah, moved forward and established strongly fortified camps just north of the Wadi-ur-Ruqqad.[49][j]

The right flank of the Byzantine army was at the south end of the plains, near the Yarmuk River and about a mile before the ravines of Wadi al Allan began. The left flank of the Byzantines was at the north, a short distance before the Hills of Jabiyah began, and was relatively exposed. Vahan deployed the Imperial Army facing east, with a front about 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) long,[35] as he was trying to cover the whole area between the Yarmuk gorge in the south and the Roman road to Egypt in the north, and substantial gaps had been left between the Byzantine divisions. The right wing was commanded by Gregory and the left by Qanatir. The centre was formed by the army of Dairjan and the Armenian army of Vahan, both under the overall command of Dairjan. The Byzantine regular heavy cavalry, the cataphract, was distributed equally among the four armies, each army deploying its infantry at the forefront and its cavalry as a reserve in the rear. Vahan deployed Jabalah's Christian Arabs, mounted on horses and camels, as a skirmishing force, screening the main army until its arrival.[50]

Early Muslim sources mention that the army of Gregory had used chains to link together its foot soldiers, who had all taken an oath of death. The chains were in 10-man lengths as a proof of unshakeable courage on the part of the men, who thus displayed their willingness to die where they stood and not to retreat. The chains also acted as an insurance against a breakthrough by enemy cavalry. However, modern historians suggest that the Byzantines adopted the Graeco-Roman testudo military formation in which soldiers would stand shoulder-to-shoulder with shields held high and an arrangement of 10 to 20 men would be completely shielded on all sides from missile fire, each soldier providing cover for an adjoining companion.[35]

Weaponry

[edit]The Byzantine cavalry was armed with a long sword, known as the spathion. They would also have had a light wooden lance, known as a kontarion and a bow (toxarion) with forty arrows in a quiver, hung from a saddle or from the belt.[51] Heavy infantry, known as skoutatoi, had a short sword and a short spear. The lightly armed Byzantine troops and the archers carried a small shield, a bow hung from the shoulder across the back and a quiver of arrows. Cavalry armour consisted of a hauberk with a mail coif and a helmet with a pendant: a throat-guard lined with fabric and having a fringe and cheek piece. Infantry was similarly equipped with a hauberk, a helmet and leg armour. Light lamellar and scale armour was also used.[52]

Tensions in Byzantine army

[edit]Khalid's strategy of withdrawing from the occupied areas and concentrating all of his troops for a decisive battle forced the Byzantines to concentrate their five armies in response. The Byzantines had for centuries avoided engaging in large-scale decisive battles, and the concentration of their forces created logistical strains for which the empire was ill-prepared.[33][53]

Damascus was the closest logistical base, but Mansur, leader of Damascus, could not fully supply the massive Byzantine army that was gathered at the Yarmuk plain. Several clashes were reported with local citizens over supply requisition, as summer was at an end and there was a decline of pasturage. Greek court sources accused Vahan of treason for his disobedience to Heraclius' command not to engage in large-scale battle with Arabs. Given the massing of the Muslim armies at Yarmuk, however, Vahan had little choice but to respond in kind. Relations between the various Byzantine commanders were also fraught with tension. There was a struggle for power between Trithurios and Vahan, Jarajis, and Qanatir (Buccinator).[54] Jabalah, the Christian Arab leader, was largely ignored, to the detriment of the Byzantines given his knowledge of the local terrain. An atmosphere of mistrust thus existed between the Romans, Armenians and Arabs. Longstanding ecclesiastical feuds between the Monophysite and Chalcedonian factions, of negligible direct impact, certainly inflamed underlying tensions. The effect of the feuds was decreased coordination and planning, one of the reasons for the catastrophic Byzantine defeat.[55]

Battle

[edit]The battle lines of the Muslims and the Byzantines were divided into four sections: the left wing, the left centre, the right centre and the right wing. Note that the descriptions of the Muslim and the Byzantine battle lines are exactly each other's opposite: the Muslim right wing faced the Byzantine left wing (see image[n]).

Vahan was instructed by Heraclius not to engage in battle until all avenues of diplomacy had been explored,[56] probably because Yazdegerd III's forces were not yet ready for the offensive in Iraq. Accordingly, Vahan sent Gregory and then Jabalah to negotiate, but their efforts proved futile. Before the battle, on Vahan's invitation, Khalid came to negotiate peace, with a similar end. The negotiations delayed the battles for a month.[35]

On the other hand, Umar, whose forces at Qadisiyah were threatened with confronting the Sassanid armies, ordered Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas to enter negotiations with the Persians and to send emissaries to Yazdegerd III and his commander Rostam Farrokhzād, apparently inviting them to Islam. That was most probably the delaying tactic employed by Umar on the Persian front.[57] Meanwhile, he sent reinforcements[35] of 6,000 troops, mostly from Yemen, to Khalid. The force included 1,000 Sahaba (companions of Muhammad), among whom were 100 veterans of the Battle of Badr, the first battle in Islamic history, and included citizens of the highest rank, such as Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, Abu Sufyan, and his wife Hind bint Utbah.[58]

Also present were such distinct companions as Sa'id ibn Zayd, Fadl ibn Abbas, Abdul-Rahman ibn Abi Bakr (the son of Abu Bakr), Abdullah ibn Umar (the son of Umar), Aban ibn Uthman (the son of Uthman), Abdulreman ibn Khalid (the son of Khalid), Abdullah ibn Ja'far (the nephew of Ali), Ammar ibn Yasir, Miqdad ibn Aswad, Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Malik al-Ashtar, Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, Qays ibn Sa'd, Hudhayfah ibn al-Yaman, Ubada ibn as-Samit, Hisham ibn al-A'as, Abu Huraira and Ikrimah ibn Abi Jahl.[59] As it was a citizen army, in contrast to a mercenary army, the age of the soldiers ranged from 20 (in the case of Khalid's son) to 70 (in the case of Ammar). Three of the ten companions promised paradise by Muhammad, namely Sa'id, Zubayr and Abu Ubaidah, were present at Yarmuk.

Umar, apparently wanting to defeat the Byzantines first, used the best Muslim troops against them. The continuing stream of Muslim reinforcements worried the Byzantines, who fearing that the Muslims with such reinforcements would grow powerful, decided that they had no choice but to attack. The reinforcements that were sent to the Muslims at Yarmuk arrived in small bands, giving the impression of a continuous stream of reinforcements to demoralize the Byzantines to compel them to attack.[60] The same tactic would be repeated again during the Battle of Qadisiyah.[45]

Day 1

[edit]

The battle began on 15 August.[61] At dawn, both armies lined up for battle less than a mile apart. It is recorded in Muslim chronicles that before the battle started, George, a unit commander in the Byzantine right centre, rode up to the Muslim line and converted to Islam; he would die the same day fighting on the Muslim side.[62] The battle began as the Byzantine army sent its champions to duel with the Muslim mubarizun. The mubarizun were specially trained swordsmen and lancers, with the objective to slay as many enemy commanders as possible to damage their morale. At midday, after losing a number of commanders in the duels, Vahan ordered a limited attack with a third of his infantry forces to test the strength and strategy of the Muslim army and, using their overwhelming numerical and weaponry superiority, achieve a breakthrough wherever the Muslim battle line was weak. However the Byzantine assault lacked determination; many Byzantine soldiers were unable to press the attack against the Muslim veterans.[63] The fighting was generally moderate although in some places, it was especially intense. Vahan did not reinforce his forward infantry, two thirds of which was kept in reserve with one third deployed to engage the Muslims, and at sunset, both armies broke contact and returned to their respective camps.[62]

Day 2

[edit]

Phase 1: On 16 August, Vahan decided in a council of war to launch his attack just before dawn, to catch the Muslim force unprepared as they conducted their morning prayers. He planned to engage his two central armies with the Muslim centre in an effort to stall them while the main thrusts would be against the wings of the Muslim army, which would then be driven away from the battlefield or pushed towards the centre.[62][64] To observe the battlefield, Vahan had a large pavilion built behind his right wing with an Armenian bodyguard force. He ordered the army to prepare for the surprise attack.

However, Khalid had prepared for such a contingency by placing a strong outpost line in front during the night to counter surprises, which gave the Muslims time to prepare for battle. At the centre, the Byzantines did not press hard, intending to pin down the Muslim centre corps in their position and preventing them from aiding the Muslim army in other areas. Thus the centre remained stable, but on the wings the situation was different. Qanatir, commanding the Byzantine left flank, which consisted of mainly Slavs, attacked in force, and the Muslim infantry on the right flank had to retreat. Amr, the Muslim right wing commander ordered his cavalry regiment to counterattack, which neutralized the Byzantine advance and stabilized the battle line on the right for some time, but the Byzantine numerical superiority caused them to retreat towards the Muslim base camp.[65]

Phase 2: Khalid, aware of the situation at the wings, ordered the cavalry of the right wing to attack the northern flank of the Byzantine left wing while he with his mobile guard attacked the southern flank of the Byzantine left wing, and the Muslim right wing infantry attacked from the front. The three-pronged attack forced the Byzantine left wing to abandon the Muslim positions they had gained on, and Amr regained his lost ground and started reorganizing his corps for another round.[65]

The situation on the Muslim left wing, which Yazid commanded was considerably more serious. The Muslim right wing enjoyed assistance from the mobile guard but not the left wing, and the numerical advantage the Byzantines enjoyed caused the Muslim positions to be overrun, with soldiers retreating towards base camps.[58] There, the Byzantines had broken through the corps. The testudo formation that Gregory's army had adopted moved slowly but also had a good defence. Yazid used his cavalry regiment to counterattack but was repulsed. Despite stiff resistance, the warriors of Yazid on the left flank finally fell back to their camps and for a moment Vahan's plan appeared to be succeeding. The centre of the Muslim army was pinned down and its flanks had been pushed back. However, neither flank had broken though morale was severely damaged.[66]

The retreating Muslim army was met by the ferocious Arab women in the camps.[58] Led by Hind, the Muslim women dismantled their tents, and armed with tent poles, charged at their husbands and fellow men singing an improvised song from the Battle of Uhud, which then had been directed against the Muslims.

We are the daughters of the night;

We move amongst the cushions,

With the grace of gentle kittens

Our bracelets on our elbows.

If you attack we shall embrace you;

And if you retreat we will forsake you

With a loveless separation.[65]

That boiled the blood of the retreating Muslims so much that they returned to the battlefield.[67]

Phase 3: After managing to stabilize the position on the right flank, Khalid ordered the mobile guard cavalry to provide relief to the battered left flank.

Khalid detached one regiment under Dharar ibn al-Azwar and ordered him to attack the front of the army of Dairjan (left centre) to create a diversion and threaten the withdrawal of the Byzantine right wing from its advanced position. With the rest of the cavalry reserve he attacked Gregory's flank. Here again, under simultaneous attacks from the front and flanks, the Byzantines fell back but more slowly because they had to maintain their formation.[68]

At sunset, the central armies broke contact and withdrew to their original positions and both fronts were restored along the lines occupied in the morning. The death of Dairjan and the failure of Vahan's battle plan left the larger Imperial army relatively demoralized, but Khalid's successful counterattacks emboldened his troops despite their being smaller in number.[69]

Day 3

[edit]

On 17 August, Vahan pondered over his failures and mistakes of the previous day, where he launched attacks against respective Muslim flanks, but after initial success, his men were pushed back. What bothered him the most was the loss of one of his commanders.[citation needed]

The Byzantine army decided on a less ambitious plan, and Vahan now aimed to break the Muslim army at specific points. He decided to press upon the relatively exposed right flank, where his mounted troops could maneuver more freely as compared to the rugged terrain at the Muslims' left flank. The junction was to be between the Muslim right centre, its right wing held by Qanatir's Slavs, to break them apart so that they would be fought separately.[citation needed]

Phase 1: The battle resumed with Byzantine attacks on the Muslim right flank and right centre.[70]

After holding off the initial attacks by the Byzantines, the Muslim right wing fell back, followed by the right centre. They were again said to have been met by their own women, who abused and shamed them. The corps, however, managed to reorganize some distance from the camp and held their ground preparing for a counterattack.[65]

Phase 2: Knowing that the Byzantine army was focusing on the Muslim right, Khalid ibn al-Walid launched an attack with his mobile guard, along with the Muslim right flank cavalry. Khalid ibn al-Walid struck at the right flank of the Byzantines left centre, and the cavalry reserve of the Muslims right centre struck at the Byzantines left centre at its left flank. Meanwhile, he ordered the Muslims' right-wing cavalry to strike at the left flank of the Byzantines left wing. The combat soon developed into a bloodbath. Many fell on both sides. Khalid's timely flanking attacks again saved the day for Muslims and by dusk, the Byzantines had been pushed back to the positions they had at the start of the battle.[65]

Day 4

[edit]

Phase 1: Vahan decided to persist with the previous day's war plan as he had been successful in inflicting damage on the Muslim right.

Qanatir led two armies of Slavs against the Muslim right wing and right centre with some assistance from the Armenians and Christian Arabs led by Jabalah. The Muslim right wing and right centre again fell back.[71] Khalid entered the fray yet again with the mobile guard. He feared a general attack on a broad front, which he would be unable to repulse, and so ordered Abu Ubaidah and Yazid on the left centre and the left wings, respectively, to attack the Byzantine armies at the respective fronts. The attack would result in stalling the Byzantine front and prevent a general advance of the Imperial army.[72]

Phase 2: Khalid divided his mobile guard into two divisions and attacked the flanks of the Byzantine left centre, and the infantry of the Muslim right centre attacked from the front. Under the three-pronged flanking maneuver, the Byzantines fell back. Meanwhile, the Muslim right wing renewed its offense with its infantry attacking from the front and the cavalry reserve attacking the northern flank of the Byzantine left wing. As the Byzantine left centre retreated under three-pronged attacks of Khalid, the Byzantine left wing, having been exposed at its southern flank, also fell back.[71]

While Khalid and his mobile guard were dealing with the Armenian front throughout the afternoon, the situation on the other end was worsening.[73] Byzantine horse-archers had taken to the field and subjected Abu Ubaidah and Yazid's troops to intense archery preventing them from penetrating their Byzantine lines. Many Muslim soldiers lost their sight to Byzantine arrows on that day, which thereafter became known as the "Day of Lost Eyes".[74] The veteran Abu Sufyan is also believed to have lost an eye that day.[74] The Muslim armies fell back except for one regiment, led by Ikrimah bin Abi Jahal, which was on the left of Abu Ubaidah's corps. Ikrimah covered the retreat of the Muslims with his 400 members of the cavalry by attacking the Byzantine front, and the other armies reorganized themselves to counterattack and regain their lost positions. All of Ikrimah's men were either seriously injured or dead that day. Ikrimah, a childhood friend of Khalid, was mortally wounded and died later in the evening.[73]

Day 5

[edit]

During the four-day offence of Vahan, his troops had failed to achieve any breakthrough and had suffered heavy casualties, especially during the mobile guard's flanking counterattacks. Early on 19 August, the fifth day of the battle, Vahan sent an emissary to the Muslim camp for a truce for the next few days so that fresh negotiations could be held. He supposedly wanted time to reorganize his demoralized troops, but Khalid deemed victory to be in reach and he declined the offer.[75]

Until now, the Muslim army had adopted a largely defensive strategy, but knowing that the Byzantines were apparently no longer eager for battle, Khalid now decided to take the offensive and reorganized his troops accordingly. All cavalry regiments were grouped together into one powerful mounted force with the mobile guard acting as its core. The total strength of the cavalry group was now about 8,000 mounted warriors, an effective mounted corps for an offensive attack the next day. The rest of the day passed uneventfully. Khalid planned to trap Byzantine troops, cutting off their every route of escape. There were three natural barriers, the three gorges in the battlefield with their steep ravines, Wadi-ur-Ruqqad at west, Wadi al Yarmouk in south and Wadi al Allah in east. The northern route was to be blocked by Muslim cavalry.[76]

There were however, some passages across the 200 metres (660 ft) deep ravines of Wadi-ur-Raqqad in west, strategically the most important one was at Ayn al Dhakar, a bridge. Khalid sent Dharar with 500 cavalry at night to secure that bridge. Dharar moved around the northern flank of Byzantines and captured the bridge, a maneuver that was to prove decisive the next day.[77]

Day 6

[edit]

On 20 August,[78] Khalid put into action a simple but bold plan of attack. With his massed cavalry force, he intended to drive the Byzantine cavalry entirely off the battlefield so that the infantry, which formed the bulk of the imperial army, would be left without cavalry support and thus would be exposed when attacked from the flanks and rear. At the same time, he planned to push a determined attack to turn the left flank of the Byzantine army and drive them towards the ravine to the west.[77]

Phase 1: Khalid ordered a general attack on the Byzantine front and galloped his cavalry around the left wing of the Byzantines. Part of his cavalry engaged the Byzantine left wing cavalry while the rest of it attacked the rear of the Byzantine left wing infantry. Meanwhile, the Muslim right wing pressed against it from the front. Under the two-pronged attack, the Byzantine left wing fell back and collapsed and fell back to the Byzantine left centre, greatly disordering it.[75] The remaining Muslim cavalry then attacked the Byzantine left wing cavalry at the rear while they were held frontally by the other half of the Muslim cavalry, routing them off the battlefield to the north. The Muslim right-wing infantry now attacked the Byzantine left centre at its left flank while the Muslim right centre attacked from front.

Phase 2: Vahan, noticing the huge cavalry maneuver of the Muslims, ordered his cavalry to group together, but was not quick enough. Before Vahan could organize his disparate heavy cavalry squadrons, Khalid had wheeled his cavalry back to attack the concentrating Byzantine cavalry squadrons, falling upon them from the front and the flank while they were still moving into formation. The disorganized and disoriented Byzantine heavy cavalry was soon routed and dispersed to the north, leaving the infantry to its fate.[79]

Phase 3: With the Byzantine cavalry completely routed, Khalid turned to the Byzantine left centre, which already held the two-pronged attack of the Muslim infantry. The Byzantine left centre was attacked at its rear by Khalid's cavalry and was finally broken.[79]

Phase 4: With the retreat of the Byzantine left centre, a general Byzantine retreat started. Khalid took his cavalry north to block the northern route of escape. The Byzantines retreated west towards Wadi-ur-Ruqqad, where there was a bridge at Ayn al Dhakar for safe crossing across the deep gorges of the ravines of Wadi-ur-Ruqqad.[73] Dharar had already captured the bridge as part of Khalid's plan the night before. A unit of 500 mounted troops had been sent to block the passageway. In fact, that was the route by which Khalid wanted the Byzantines to retreat all along. The Byzantines were surrounded from all sides now.[75][k]

Some fell into the deep ravines off the steep slopes, others tried to escape in the waters but were smashed on the rocks below and still others were killed in their flight. Nevertheless, many of the soldiers managed to escape the slaughter.[80] Jonah, the Greek informant of the Rashidun army during the conquest of Damascus, died in the battle. The Muslims took no prisoners in the battle, but they may have captured some during the subsequent pursuit.[81] Theodore Trithyrius was killed on the battlefield,[82] and Niketas managed to escape and reach Emesa. Jabalah ibn al-Ayham also managed to escape and later briefly came to terms with the Muslims, but he soon defected to the Byzantine court again.[83]

Aftermath

[edit]Immediately after the operation was over, Khalid and his mobile guard moved north to pursue the retreating Byzantine soldiers and found them near Damascus and attacked. Vahan, who had escaped the fate of most of his men at Yarmuk, was probably killed in the ensuing fighting.[84] Khalid then entered Damascus, where he was welcomed by the local residents, thus recapturing the city.[30][85]

When news of the disaster reached Heraclius at Antioch,[86] the emperor was devastated and enraged. He blamed his wrongdoings for the loss, primarily referring to his incestuous marriage to his niece Martina.[87] He would have tried to reconquer the province if he had the resources[86] but now had neither the men nor the money to defend the province any more. Instead, he retreated to the cathedral of Antioch, where he observed a solemn service of intercession.[86] He summoned a meeting of his advisers at the cathedral and scrutinized the situation. He was told almost unanimously and accepted the fact that the defeat was God's decision and a result of the sins of the people of the land, including him.[88] Heraclius took to the sea on a ship to Constantinople in the night.

His ship supposedly set sail, and he bade a last farewell to Syria,:

Farewell, a long farewell to Syria, my fair province. Thou art an infidel's (enemy's) now. Peace be with you, O Syria—what a beautiful land you will be for the enemy's hands.[86][88]

Heraclius abandoned Syria with the holy relic of the True Cross, which was, along with other relics held at Jerusalem, secretly boarded on ship by Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem,[86] just to protect it from the invading Arabs. It is said that he had a fear of water,[89] and a pontoon bridge was made for Heraclius to cross the Bosphorus to Constantinople. After abandoning Syria, he began to concentrate on his remaining forces for the defence of Anatolia and Egypt instead. Byzantine Armenia fell to the Muslims in 638–39, and Heraclius created a buffer zone in central Anatolia by ordering all the forts east of Tarsus to be evacuated.[90]

In 639–642 the Muslims, led by Amr ibn al-A'as, who had commanded the right flank of the Rashidun army at Yarmuk, invaded and captured Byzantine Egypt.[91]

Evaluation

[edit]The Imperial Byzantine commanders allowed their enemy to have the battlefield of his choosing. Even then, they were at no substantial tactical disadvantage.[49] Khalid knew all along that he was up against a force superior in numbers and, until the last day of the battle, conducted an essentially defensive campaign, suited to his relatively limited resources. When he decided to take the offensive and attack on the final day of battle, he did so with a degree of imagination, foresight and courage that none of the Byzantine commanders managed to display. Although he commanded a smaller force and needed all the men he could muster, he had the confidence and foresight to dispatch a cavalry regiment the night before his assault to seal off a critical path of the retreat that he had anticipated for the enemy army.[77]

Because of his leadership at Yarmuk, Khalid ibn al-Walid is considered one of the finest generals in history,[6] and his use of mounted warriors throughout the battle showed just how well he understood the potential strengths and weaknesses of his mounted troops. His mobile guard moved quickly from one point to another, always changed the course of events wherever they appeared, and, then just as quickly, galloped away to change the course of events elsewhere on the field.[92]

Vahan and his Byzantine commanders did not manage to deal with the mounted force and use the sizable advantage of their army effectively.[93] Their own Byzantine cavalry never played a significant role in the battle and were held in static reserve for most of the six days.[60] They never pushed their attacks, and even when they obtained what could have been a decisive breakthrough on the fourth day, they were unable to exploit it. There appeared to be a decided lack of resolve among the Imperial commanders, but that may have been caused by difficulties commanding the army because of internal conflict. Moreover, many of the Arab auxiliaries were mere levies, but the Muslim Arab army consisted for a much larger part of veteran troops.[94]

The original strategy of Heraclius, to destroy the Muslim troops in Syria, needed a rapid and quick deployment, but the commanders on the ground never displayed those qualities. Ironically, on the field at Yarmuk, Khalid carried out, on a small tactical scale, what Heraclius had planned on a grand strategic scale. By rapidly deploying and maneuvering his forces, Khalid was able to concentrate sufficient forces at specific locations on the field temporarily to defeat the larger Byzantine army in detail. Vahan was never able to make his numerical superiority count, perhaps because of the terrain, which prevented large-scale deployment.[citation needed]

However, Vahan never attempted to concentrate a superior force to achieve a critical breakthrough.[95] Although he was on the offensive five out of the six days, his battle line remained remarkably static. That stands in stark contrast to the very successful offensive plan, which Khalid carried out on the final day by reorganising virtually all his cavalry and committing it to a grand maneuver, which won the battle.[92]

George F. Nafziger, in his book Islam at war, described the battle:

Although Yarmouk is little known today, it is one of the most decisive battles in human history...... Had Heraclius' forces prevailed, the modern world would be so changed as to be unrecognizable.[4]

Notes

[edit]| History of Syria |

|---|

|

| Prehistory |

| Bronze Age |

| Antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

|

| Early modern |

|

| Modern |

|

| Related articles |

| Timeline |

|

|

^ a: Modern estimates for Roman army:

Donner 1981: 20,000–40,000.[96]

Nicolle 1994: (p. 32) Maximum 25,000 with an unstated number of Arab reinforcements. (p. 65) 15,000–20,000.[97]

Akram 1970: 150,000.[98]

Kaegi 2003 (p. 242): 15,000–20,000, possibly more[99]

Kennedy 2006 (p. 131): 15,000–20,000, [100]

^ b: Roman source for Roman army:

Theophanes (pp. 337–338): 80,000 Roman troops (Kennedy, 2006, p. 145) and 60,000 allied Ghassanid troops (Gibbon, Vol. 5, p. 325).

^ c: Early Muslim sources for Roman army:

Baladhuri (p. 140): 200,000.[specify][verification needed]

Tabari (Vol. 2, p. 598): 200,000.[specify][verification needed]

Ibn Ishaq (Tabari, Vol. 3, p. 75): 100,000 against 24,000 Muslims.[specify][verification needed]

^ d: Modern estimates for Muslim army:

Kaegi 1995: 15,000–20,000 maximum[page needed][verification needed]

Nicolle 1994: (p. 43) 20,000–40,000, likely 25,000.

Akram: 40,000 maximum.[page needed][verification needed]

Treadgold 1997: 24,000[page needed][verification needed]

^ e: Primary sources for Muslim army:

Ibn Ishaq (Vol. 3, p. 74): 24,000.[specify][verification needed]

Baladhuri: 24,000.[specify][verification needed]

Tabari (Vol. 2, p. 592): 40,000.[specify][verification needed]

^ f: Primary sources for Roman casualties:

Tabari (Vol. 2, p. 596): 120,000 killed.[specify][verification needed]

Ibn Ishaq (Vol. 3, p. 75): 70,000 killed.[specify][verification needed]

Baladhuri (p. 141): 70,000 killed.[specify][verification needed]

^ g: His name is mentioned in Islamic sources as Jaban, Vahan Benaas and Mahan. Vahan is most likely to be his name as it is of Armenian origin

^ i: During the reign of Abu Bakr, Khalid ibn Walid remained the Commander-in-Chief of the army in Syria but at Umar's accession as Caliph he dismissed him from command. Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah became the new commander in chief. (See Dismissal of Khalid).

^ j: Some Byzantine sources also mention a fortified encampment at Yaqusah, 18 kilometres (11 mi) from the battlefield. E.g., A. I. Akram suggests that the Byzantine camps were north of Wadi-ur-Ruqqad, while David Nicolle agrees with early Armenian sources, which positioned camps at Yaqusah (See: Nicolle p. 61 and Akram 2004 p. 410).

^ k: Akram misinterprets the bridge at 'Ayn Dhakar for a ford while Nicolle explains the exact geography (See: Nicolle p. 64 and Akram p. 410)

^ n: Concepts used in the description of the battle lines of the Muslims and the Byzantines. See image-1.

References

[edit]- ^ Nicolle 1994, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 425.

- ^ Britannica (2007): "Losses: Byzantine allied, 40,000"

- ^ a b Nafziger & Walton 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 6.

- ^ a b Nicolle 1994, p. 19.

- ^ Haldon 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 189–90.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 217–27.

- ^ Haldon 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Luttwak 2009, p. 199.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 87.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 246.

- ^ Runciman 1987, p. 15.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 298.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 60.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 112.

- ^ Akram 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 402.

- ^ Al-Waqidi, p. 100

- ^ (in Armenian) Bartikyan, Hrach. «Վահան» (Vahan). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. vol. xi. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1985, p. 243.

- ^ Kennedy 2007, p. 82.

- ^ a b Akram 2004, p. 409.

- ^ Al-Waqidi, p. 106.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 399.

- ^ a b Nicolle 1994, p. 61.

- ^ a b Kaegi 1995, p. 67.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 401.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, p. 143.

- ^ a b Kaegi 1995, p. 134.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 407.

- ^ a b c d e Nicolle 1994, p. 64.

- ^ Schumacher, Oliphant & Le Strange 1889, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 122.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 63.

- ^ a b Jandora, John W. (1985). "The Battle of the Yarmūk: A Reconstruction". Journal of Asian History. 19 (1): 8–21. ISSN 0021-910X.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 242: "The Byzantines, together with their Christian Arab allies, probably enjoyed numerical superiority, having troops that totalled up to 15–20,000 men, possibly more." Haldon 2008, pp. 48–49: "The numbers fighting on each side are impossible to determine. [...] A total imperial force of about 20,000 would, therefore, be not unreasonable, although this remains a guess."

- ^ a b Reich, Aaron (20 April 2021). "On This Day: Arabs defeat the Byzantines at Battle of Yarmuk". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 1994, p. 66.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 34.

- ^ Nafziger & Walton 2003, p. 29.

- ^ a b Akram 2004, p. 411.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 413.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 39.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 36.

- ^ a b Kaegi 1995, p. 124.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 65.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 29.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 30.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 121.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 130.

- ^ Akram 2009, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 1994, p. 70.

- ^ "The Islamic Conquest of Syria". Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b Kaegi 1995, p. 129.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 1994, p. 68.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 415.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 417.

- ^ a b c d e Nicolle 1994, p. 71.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 418.

- ^ Regan 2003, p. 164.

- ^ Akram 2004, pp. 418–19.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 419.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 420.

- ^ a b Nicolle 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 421.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 1994, p. 75.

- ^ a b Al-Waqidi, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 1994, p. 76.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 422.

- ^ a b c Akram 2004, p. 423.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 114.

- ^ a b Akram 2004, p. 424.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 138.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 128.

- ^ Kennedy 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Nicolle 1994, p. 80.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 273.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 426.

- ^ a b c d e Runciman 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Runciman 1987, p. 96.

- ^ a b Regan 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Regan 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, pp. 148–49.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 327.

- ^ a b Nicolle 1994, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 137.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 408.

- ^ Kaegi 1995, p. 143.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 221.

- ^ Nicolle 1994.

- ^ Akram 2004, p. 425.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 242.

- ^ Kennedy 2006, p. 131.

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Al-Baladhuri (1924). Kitab Futuh Al-buldan: The Origins Of The Islamic State Vol 2. Translated by Murgotten, Francis Clark. New York: Columbia University.

- Futuh al Sham (The Islamic Conquest of Syria). Translated by al-Kindi, Mawlana Sulayman. Ta-Ha Publishers. 2002.

- Chronicle of Fredegar. 658.

- Dionysius Telmaharensis (774). Chronicle of Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre.

- Ibn Ishaq (2004). Sirah Rasul Allah [The Life of Muhammad]. Translated by Guillaume, Alfred. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780196360331.

- Ibn Khaldun (2020). Nessim Joseph, Dawood (ed.). Muqaddimah [Introduction]. Translated by Rosenthal, Franz. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvwh8dcw. ISBN 9781400866090. JSTOR j.ctvwh8dcw.

- The Maronite Chronicles, 664

- Pseudo-Methodius (2012). Garstad, Benjamin (ed.). Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674053076.

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (1987). Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). History of the Prophets and Kings. SUNY series in Near Eastern Studies. Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. Translated by Brinner, William M. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. doi:10.2307/jj.18252170. ISBN 9780887063138. JSTOR jj.18252170.

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (2015). Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). History of the Prophets and Kings. SUNY series in Near Eastern Studies. Vol. 2: The Children of Israel. Translated by Brinner, William M. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. doi:10.2307/jj.18252188. ISBN 9780791497524. JSTOR jj.18252188.

- Theophanes the Confessor (1997). Chronographia. Translated by Mango, Cyril; Scott, Roger. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198225683.

- Thomas the Presbyter, Chronicle

- Fragment on the Arab Conquests, 636

- Chronicle of 819

Secondary sources

[edit]Journals

[edit]- Conrad, Lawrence I. (1988). "Seven and the Tasbīʿ: On the Implications of Numerical Symbolism for the Study of Medieval Islamic History". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 31 (1): 42–73. doi:10.2307/3631765. JSTOR 3631765.

- Jandora, John W. (1986). "Developments in Islamic Warfare: The Early Conquests". Studia Islamica (64): 101–113. doi:10.2307/1596048. JSTOR 1596048.

Books

[edit]- Akram, A. I. (1970). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. Rawalpindi: Nat. Publishing House. ISBN 0-7101-0104-X.

- Akram, A. I. (2004). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed – His Life and Campaigns (3rd ed.). ISBN 0-19-597714-9.

- Akram, A. I. (2009). Muslim conquest of Persia (3rd ed.). Maktabah Publications. ISBN 978-0-9548665-3-2.

- Donner, Fred McGraw (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton Studies on the Near East. Vol. 1017. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400847877. ISBN 9780691053271.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N.C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–628 AD). Oxford and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203994542. ISBN 9780203994542.

- Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Translated by Broido, Ethel. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521599849.

- Haldon, John (1997). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: the Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511582318. ISBN 9780521319171.

- Haldon, John (2008). The Byzantine Wars. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9652-8.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (1997). Seeing Islam as Others Saw It. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam. Vol. 13. Darwin Press. ISBN 9780878501250.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (1995). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511470615. ISBN 9780521484558.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (2003). Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521814591.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2006). The Byzantine And Early Islamic Near East. Ashgate Publishing. doi:10.4324/9781003554196. ISBN 9780754659099.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2007). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81740-3.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03519-5.

- Nafziger, George F.; Walton, Mark W. (2003). Islam at War. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780275981013.

- Nicolle, David (1994). Yarmuk 636 A.D.: The Muslim Conquest of Syria. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855324145.

- Palmer, Andrew (1993). The Seventh Century in the West-Syrian Chronicles. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. doi:10.3828/9780853232384. ISBN 9780853232384.

- Regan, Geoffrey (2003). First Crusader: Byzantium's Holy Wars (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403961518.

- Runciman, Steven (1987). A History of the Crusades: The First Crusade (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-521-34770-9.

- Schumacher, Gottlieb; Oliphant, Laurence; Le Strange, Guy (1889). Across the Jordan; being an exploration and survey of part of Hauran and Jaulan. London: Alexander P. Watt.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. doi:10.1515/9780804779371. ISBN 9780804779371.

- Woods, David (2007). "Jews, Rats, and the Battle of Yarmūk". In Ariel S. Lewin; Pietrina Pellegrini (eds.). The Late Roman Army in the Near East from Diocletian to the Arab Conquest. Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-4073-0161-7.

External links

[edit]- Yarmouk in Sword of Allah at GrandeStrategy by A. I. Akram

- Battle of Yarmuk, 636