Dog

| Dog Temporal range: Late Pleistocene to present[1]

| |

|---|---|

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. familiaris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Canis familiaris | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List

| |

The dog (Canis familiaris or Canis lupus familiaris) is a domesticated descendant of the wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from an extinct population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers. The dog was the first species to be domesticated by humans, over 14,000 years ago and before the development of agriculture. Experts estimate that due to their long association with humans, dogs have gained the ability to thrive on a starch-rich diet that would be inadequate for other canids.[4]

Dogs have been bred for desired behaviors, sensory capabilities, and physical attributes.[5] Dog breeds vary widely in shape, size, and color. They have the same number of bones (with the exception of the tail), powerful jaws that house around 42 teeth, and well-developed senses of smell, hearing, and sight. Compared to humans, dogs have an inferior visual acuity, a superior sense of smell, and a relatively large olfactory cortex. They perform many roles for humans, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, companionship, therapy, aiding disabled people, and assisting police and the military.

Communication in dogs includes eye gaze, facial expression, vocalization, body posture (including movements of bodies and limbs), and gustatory communication (scents, pheromones, and taste). They mark their territories by urinating on them, which is more likely when entering a new environment. Over the millennia, dogs became uniquely adapted to human behavior; this adaptation includes being able to understand and communicate with humans. As such, the human–canine bond has been a topic of frequent study, and dogs' influence on human society has given them the sobriquet of "man's best friend".

The global dog population is estimated at 700 million to 1 billion, distributed around the world. The dog is the most popular pet in the United States, present in 34–40% of households. In developed countries, around 20% of dogs are kept as pets, while 75% of the population in developing countries largely consists of feral and community dogs.

Taxonomy

| Canine phylogeny with ages of divergence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram and divergence of the gray wolf (including the domestic dog) among its closest extant relatives[6] |

Dogs are domesticated members of the family Canidae. They are classified as a subspecies of Canis lupus, along with wolves and dingoes.[7][8] Dogs were domesticated from wolves over 14,000 years ago by hunter-gatherers, before the development of agriculture.[9][10] The dingo and the related New Guinea singing dog resulted from the geographic isolation and feralization of dogs in Oceania over 8,000 years ago.[11][12]

Dogs, wolves, and dingoes have sometimes been classified as separate species.[8] In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus assigned the genus name Canis (which is the Latin word for "dog")[13] to the domestic dog, the wolf, and the golden jackal in his book, Systema Naturae. He classified the domestic dog as Canis familiaris and, on the next page, classified the grey wolf as Canis lupus.[2] Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its upturning tail (cauda recurvata in Latin term), which is not found in any other canid.[14] In the 2005 edition of Mammal Species of the World, mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed the wolf as a wild subspecies of Canis lupus and proposed two additional subspecies: familiaris, as named by Linnaeus in 1758, and dingo, named by Meyer in 1793. Wozencraft included hallstromi (the New Guinea singing dog) as another name (junior synonym) for the dingo. This classification was informed by a 1999 mitochondrial DNA study.[3]

The classification of dingoes is disputed and a political issue in Australia. Classifying dingoes as wild dogs simplifies reducing or controlling dingo populations that threaten livestock. Treating dingoes as a separate species allows conservation programs to protect the dingo population.[15] Dingo classification affects wildlife management policies, legislation, and societal attitudes.[16] In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/Species Survival Commission's Canid Specialist Group considered the dingo and the New Guinea singing dog to be feral Canis familiaris. Therefore, it did not assess them for the IUCN Red List of threatened species.[17]

Domestication

The earliest remains generally accepted to be those of a domesticated dog were discovered in Bonn-Oberkassel, Germany. Contextual, isotopic, genetic, and morphological evidence shows that this dog was not a local wolf.[18] The dog was dated to 14,223 years ago and was found buried along with a man and a woman, all three having been sprayed with red hematite powder and buried under large, thick basalt blocks. The dog had died of canine distemper.[19] This timing indicates that the dog was the first species to be domesticated[20][21] in the time of hunter-gatherers,[22] which predates agriculture.[1] Earlier remains dating back to 30,000 years ago have been described as Paleolithic dogs, but their status as dogs or wolves remains debated[23] because considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves during the Late Pleistocene.[1]

DNA sequences show that all ancient and modern dogs share a common ancestry and descended from an ancient, extinct wolf population that was distinct from any modern wolf lineage. Some studies have posited that all living wolves are more closely related to each other than to dogs,[24][22] while others have suggested that dogs are more closely related to modern Eurasian wolves than to American wolves.[25]

The dog is a domestic animal that likely travelled a commensal pathway into domestication (i.e. dogs neither benefited nor got harmed).[23][26] The questions of when and where dogs were first domesticated remains uncertain.[20] Genetic studies suggest a domestication process commencing over 25,000 years ago, in one or several wolf populations in either Europe, the high Arctic, or eastern Asia.[27] In 2021, a literature review of the current evidence infers that the dog was domesticated in Siberia 23,000 years ago by ancient North Siberians, then later dispersed eastward into the Americas and westward across Eurasia,[18] with dogs likely accompanying the first humans to inhabit the Americas.[18] Some studies have suggested that the extinct Japanese wolf is closely related to the ancestor of domestic dogs.[28]

In 2018, a study identified 429 genes that differed between modern dogs and modern wolves. As the differences in these genes could also be found in ancient dog fossils, these were regarded as being the result of the initial domestication and not from recent breed formation. These genes are linked to neural crest and central nervous system development. These genes affect embryogenesis and can confer tameness, smaller jaws, floppy ears, and diminished craniofacial development, which distinguish domesticated dogs from wolves and are considered to reflect domestication syndrome. The study concluded that during early dog domestication, the initial selection was for behavior. This trait is influenced by those genes which act in the neural crest, which led to the phenotypes observed in modern dogs.[29]

Breeds

There are around 450 official dog breeds, the most of any mammal.[27][30] They began diversifying in the Victorian era, when humans took control of their natural selection.[21] Most breeds were derived from small numbers of founders within the last 200 years.[21][27] Since then, dogs have undergone rapid phenotypic change and have been subjected to artificial selection by humans. The skull, body, and limb proportions between breeds display more phenotypic diversity than can be found within the entire order of carnivores. These breeds possess distinct traits related to morphology, which include body size, skull shape, tail phenotype, fur type, and colour.[21] As such, humans have longed used dogs for their desirable traits to complete or fulfill a certain work or role. Their behavioural traits include guarding, herding, hunting,[21] retrieving, and scent detection. Their personality traits include hypersocial behavior, boldness, and aggression.[21] Present-day dogs are dispersed around the world.[27] An example of this dispersal is the numerous modern breeds of European lineage during the Victorian era.[22]

-

Morphological variation in six dogs

-

Phenotypic variation in four dogs

Anatomy and physiology

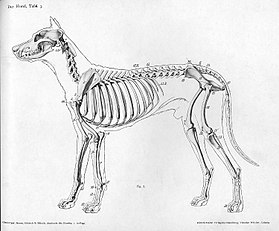

Size and skeleton

Dogs are extremely variable in size, ranging from one of the largest breeds, the Great Dane, at 50 to 79 kg (110 to 174 lb) and 71 to 81 cm (28 to 32 in), to one of the smallest, the Chihuahua, at 0.5 to 3 kg (1.1 to 6.6 lb) and 13 to 20 cm (5.1 to 7.9 in).[31][32] All healthy dogs, regardless of their size and type, have the same amount of bones with the exception of the tail, although there is significant skeletal variation between dogs of different types.[33][34] The dog's skeleton is well adapted for running; the vertebrae on the neck and back have extensions for back muscles, consisting of epaxial muscles and hypaxial muscles, to connect to; the long ribs provide room for the heart and lungs; and the shoulders are unattached to the skeleton, allowing for flexibility.[33][34][35]

Compared to the dog's wolf-like ancestors, selective breeding since domestication has seen the dog's skeleton larger in size for larger types such as mastiffs and miniaturised for smaller types such as terriers; dwarfism has been selectively bred for some types where short legs are preferred, such as dachshunds and corgis.[34] Most dogs naturally have 26 vertebrae in their tails, but some with naturally short tails have as few as three.[33]

The dog's skull has identical components regardless of breed type, but there is significant divergence in terms of skull shape between types.[34][36] The three basic skull shapes are the elongated dolichocephalic type as seen in sighthounds, the intermediate mesocephalic or mesaticephalic type, and the very short and broad brachycephalic type exemplified by mastiff type skulls.[34][36] The jaw contains around 42 teeth, and it has evolved for the consumption of flesh. Dogs use their carnassial teeth to cut food into bite-sized chunks, more especially meat.[37]

Senses

Dogs' senses include vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and magnetoreception. One study suggests that dogs can feel small variations in Earth's magnetic field.[38] Dogs prefer to defecate with their spines aligned in a north-south position in calm magnetic field conditions.[39]

Dogs' vision is dichromatic; the dog's visual world consists of yellows, blues, and grays.[40] They have difficulty differentiating between red and green,[41] and much like other mammals, the dog's eye is composed of two types of cone cells compared to the human's three. The divergence of the eye axis of dogs ranges from 12 to 25°, depending on the breed, which can have different retina configurations.[42][43] The fovea centralis area of the eye is attached to a nerve fiber, and is the most sensitive to photons.[44] Additionally, a study found that dogs' visual acuity was up to eight times less effective than a human, and their ability to discriminate levels of brightness was about two times worse than a human.[45]

While the human brain is dominated by a large visual cortex, the dog brain is dominated by a large olfactory cortex. Dogs have roughly forty times more smell-sensitive receptors than humans, ranging from about 125 million to nearly 300 million in some dog breeds, such as bloodhounds.[46] This sense of smell is the most prominent sense of the species; it detects chemical changes in the environment, allowing dogs to pinpoint the location of mating partners, potential stressors, resources, etc.[47] Dogs also have an acute sense of hearing up to four times greater than that of humans. They can pick up the slightest sounds from about 400 m (1,300 ft) compared to 90 m (300 ft) for humans.[48]

Dogs have stiff, deeply embedded hairs known as whiskers that sense atmospheric changes, vibrations, and objects not visible in low light conditions. The lower most part of whiskers hold more receptor cells than other hair types, which help in alerting dogs of objects that could collide with the nose, ears, and jaw. Whiskers likely also facilitate the movement of food towards the mouth.[49]

Coat

The coats of domestic dogs are of two varieties: "double" being common in dogs (as well as wolves) originating from colder climates, made up of a coarse guard hair and a soft down hair, or "single", with the topcoat only. Breeds may have an occasional "blaze", stripe, or "star" of white fur on their chest or underside.[50] Premature graying can occur in dogs as early as one year of age; this is associated with impulsive behaviors, anxiety behaviors, and fear of unfamiliar noise, people, or animals.[51] Some dog breeds are hairless, while others have a very thick corded coat. The coats of certain breeds are often groomed to a characteristic style, for example, the Yorkshire Terrier's "show cut".[37]

Dewclaw

A dog's dewclaw is the fifth digit in its forelimb and hind legs. Dewclaws on the forelimbs are attached by bone and ligament, while the dewclaws on the hind legs are attached only by skin. Most dogs aren't born with dewclaws in their hind legs, and some are without them in their forelimbs. Dogs' dewclaws consist of the proximal phalanges and distal phalanges. Some publications theorize that dewclaws in wolves, who usually do not have dewclaws, were a sign of hybridization with dogs.[52][53]

Tail

A dog's tail is the terminal appendage of the vertebral column, which is made up of a string of 5 to 23 vertebrae enclosed in muscles and skin that support the dog's back extensor muscles. One of the primary functions of a dog's tail is to communicate their emotional state.[54] The tail also helps the dog maintain balance by putting its weight on the opposite side of the dog's tilt, and it can also help the dog spread its anal gland's scent through the tail's position and movement.[55] Dogs can have a violet gland (or supracaudal gland) characterized by sebaceous glands on the dorsal surface of their tails; in some breeds, it may be vestigial or absent. The enlargement of the violet gland in the tail, which can create a bald spot from hair loss, can be caused by Cushing's disease or an excess of sebum from androgens in the sebaceous glands.[56]

A study suggests that dogs show asymmetric tail-wagging responses to different emotive stimuli. "Stimuli that could be expected to elicit approach tendencies seem to be associated with [a] higher amplitude of tail-wagging movements to the right side".[57][58]

Dogs can injure themselves by wagging their tails forcefully; this condition is called kennel tail, happy tail, bleeding tail, or splitting tail.[59] In some hunting dogs, the tail is traditionally docked to avoid injuries. Some dogs can be born without tails because of a DNA variant in the T gene, which can also result in a congenitally short (bobtail) tail.[60] Tail docking is opposed by many veterinary and animal welfare organisations such as the American Veterinary Medical Association[61] and the British Veterinary Association.[62] Evidence from veterinary practices and questionnaires showed that around 500 dogs would need to have their tail docked to prevent one injury.[63]

Health

Many different disorders can affect dogs. Some are congenital and others are acquired. Dogs can acquire upper respiratory tract diseases including diseases that affect the nasal cavity, the larynx, and the trachea; lower respiratory tract diseases which includes pulmonary disease and acute respiratory diseases; heart diseases which includes any cardiovascular inflammation or dysfunction of the heart; haemopoietic diseases including anaemia and clotting disorders; gastrointestinal disease such as diarrhoea and gastric dilatation volvulus; hepatic disease such as portosystemic shunts and liver failure; pancreatic disease such as pancreatitis; renal disease; lower urinary tract disease such as cystitis and urolithiasis; endocrine disorders such as diabetes mellitus, Cushing's syndrome, hypoadrenocorticism, and hypothyroidism; nervous system diseases such as seizures and spinal injury; musculoskeletal disease such as arthritis and myopathies; dermatological disorders such as alopecia and pyoderma; ophthalmological diseases such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, entropion, and progressive retinal atrophy; and neoplasia.[64]

Common dog parasites are lice, fleas, fly larvae, ticks, mites, cestodes, nematodes, and coccidia. Taenia is a notable genus with 5 species in which dogs are the definitive host.[65] Additionally, dogs are a source of zoonoses for humans. They are responsible for 99% of rabies cases worldwide;[66] however, in some developed countries such as the UK, rabies is absent from dogs and is instead only transmitted by bats.[67] Other common zoonoses are hydatid disease, leptospirosis, pasteurellosis, ringworm, and toxocariasis.[67] Common infections in dogs include canine adenovirus, canine distemper virus, canine parvovirus, leptospirosis, canine influenza, and canine coronavirus. All of these conditions have vaccines available.[67]

Dogs are the companion animal most frequently reported for exposure to toxins. Most poisonings are accidental and over 80% of reports of exposure to the ASPCA animal poisoning hotline are due to oral exposure. The most common substances people report exposure to are: pharmaceuticals, toxic foods, and rodenticides.[68] Data from the Pet Poison Helpline shows that human drugs are the most frequent cause of toxicosis death. The most common household products ingested are cleaning products. Most food related poisonings involved theobromine poisoning (chocolate). Other common food poisonings include xylitol, Vitis (grapes, raisins, etc.) and Allium (garlic, oninions, etc.). Pyrethrin insecticides were the most common cause of pesticide poisoning. Metaldehyde a common pesticide for snails and slugs typically causes severe outcomes when ingested by dogs.[69]

Neoplasia is the most common cause of death for dogs.[70][71][72] Other common causes of death are heart and renal failure.[72] Their pathology is similar to that of humans, as is their response to treatment and their outcomes. Genes found in humans to be responsible for disorders are investigated in dogs as being the cause and vice versa.[27][73]

Lifespan

The typical lifespan of dogs varies widely among breeds, but the median longevity (the age at which half the dogs in a population have died and half are still alive) is approximately 12.7 years.[74][75] Obesity correlates negatively with longevity with one study finding obese dogs to have a life expectancy approximately a year and a half less than dogs with a healthy weight.[74]

In a 2024 UK study analyzing 584,734 dogs, it was concluded that purebred dogs lived longer than crossbred dogs, challenging the previous notion of the latter having the higher life expectancies. The authors noted that their study included "designer dogs as crossbred and that purebred dogs were typically given better care than their crossbred counterparts, which likely influenced the outcome of the study.[76] Other studies also show that fully mongrel dogs live about a year longer on average than dogs with pedigrees.[77] Furthermore, small dogs with longer muzzles have been shown to have higher lifespans than larger medium-sized dogs with much more depressed muzzles.[78] For free-ranging dogs, less than 1 in 5 reach sexual maturity,[79] and the median life expectancy for feral dogs is less than half of dogs living with humans.[80]

Reproduction

In domestic dogs, sexual maturity happens around six months to one year for both males and females, although this can be delayed until up to two years of age for some large breeds. This is the time at which female dogs will have their first estrous cycle, characterized by their vulvas swelling and producing discharges, usually lasting between 4 and 20 days.[81][82] They will experience subsequent estrous cycles semiannually, during which the body prepares for pregnancy. At the peak of the cycle, females will become estrous, mentally and physically receptive to copulation. Because the ova survive and can be fertilized for a week after ovulation, more than one male can sire the same litter.[5] Fertilization typically occurs two to five days after ovulation. After ejaculation, the dogs are coitally tied for around 5–30 minutes because of the male's bulbus glandis swelling and the female's constrictor vestibuli contracting; the male will continue ejaculating until they untie naturally due to muscle relaxation.[83] 14–16 days after ovulation, the embryo attaches to the uterus, and after seven to eight more days, a heartbeat is detectable.[84][85] Dogs bear their litters roughly 58 to 68 days after fertilization,[5][86] with an average of 63 days, although the length of gestation can vary. An average litter consists of about six puppies.[87]

Neutering

Neutering is the sterilization of animals via gonadectomy, which is an orchidectomy (castration) in dogs and ovariohysterectomy (spay) in bitches. Neutering reduces problems caused by hypersexuality, especially in male dogs.[88] Spayed females are less likely to develop cancers affecting the mammary glands, ovaries, and other reproductive organs.[89] However, neutering increases the risk of urinary incontinence in bitches,[90] prostate cancer in dogs,[91] and osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, cruciate ligament rupture, pyometra, obesity, and diabetes mellitus in either sex.[92]

Neutering is the most common surgical procedure in dogs less than a year old in the US and is seen as a control method for overpopulation. Neutering often occurs as early as 6–14 weeks in shelters in the US.[93] The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) advises that dogs not intended for further breeding should be neutered so that they do not have undesired puppies that may later be euthanized.[94][95] However, the Society for Theriogenology and the American College of Theriogenologists made a joint statement that opposes mandatory neutering; they said that the cause of overpopulation in the US is cultural.[93]

Neutering is less common in most European countries, especially in Nordic countries—except for the UK, where it is common. In Norway, neutering is illegal unless for the benefit of the animal's health (e.g., ovariohysterectomy in case of ovarian or uterine neoplasia). Some European countries have similar laws to Norway, but their wording either explicitly allows for neutering for controlling reproduction or it is allowed in practice or by contradiction through other laws. Italy and Portugal have passed recent laws that promote it. Germany forbids early age neutering, but neutering is still allowed at the usual age. In Romania, neutering is mandatory except for when a pedigree to select breeds can be shown.[93][96]

Inbreeding depression

A common breeding practice for pet dogs is to mate them between close relatives (e.g., between half- and full-siblings).[97] In a study of seven dog breeds (the Bernese Mountain Dog, Basset Hound, Cairn Terrier, Brittany, German Shepherd Dog, Leonberger, and West Highland White Terrier), it was found that inbreeding decreases litter size and survival.[98] Another analysis of data on 42,855 Dachshund litters found that as the inbreeding coefficient increased, litter size decreased and the percentage of stillborn puppies increased, thus indicating inbreeding depression.[99] In a study of Boxer litters, 22% of puppies died before reaching 7 weeks of age. Stillbirth was the most frequent cause of death, followed by infection. Mortality due to infection increased significantly with increases in inbreeding.[100]

Behavior

Dog behavior has been shaped by millennia of contact with humans. They have acquired the ability to understand and communicate with humans and are uniquely attuned to human behaviors.[101][102] Behavioral scientists thought that a set of social-cognitive abilities in domestic dogs that are not possessed by the dog's canine relatives or other highly intelligent mammals, such as great apes, are parallel to children's social-cognitive skills.[103]

Most domestic animals were initially bred for the production of goods. Dogs, on the other hand, were selectively bred for desirable behavioral traits.[104][105] In 2016, a study found that only 11 fixed genes showed variation between wolves and dogs.[106] These gene variations indicate the occurrence of artificial selection and the subsequent divergence of behavior and anatomical features. These genes have been shown to affect the catecholamine synthesis pathway, with the majority of the genes affecting the fight-or-flight response[105][107] (i.e., selection for tameness) and emotional processing.[105] Compared to their wolf counterparts, dogs tend to be less timid and less aggressive, though some of these genes have been associated with aggression in certain dog breeds.[108][105] Traits of high sociability and lack of fear in dogs may include genetic modifications related to Williams-Beuren syndrome in humans, which cause hypersociability at the expense of problem-solving ability.[109] In a 2023 study of 58 dogs, some dogs classified as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-like showed lower serotonin and dopamine concentrations.[110] A similar study claims that hyperactivity is more common in male and young dogs.[111] A dog can become aggressive because of trauma or abuse, fear or anxiety, territorial protection, or protecting an item it considers valuable.[112] Acute stress reactions from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) seen in dogs can evolve into chronic stress.[113] Police dogs with PTSD can often refuse to work.[114]

Dogs have a natural instinct called prey drive (the term is chiefly used to describe training dogs' habits) which can be influenced by breeding. These instincts can drive dogs to consider objects or other animals to be prey or drive possessive behavior. These traits have been enhanced in some breeds so that they may be used to hunt and kill vermin or other pests.[115] Puppies or dogs sometimes bury food underground. One study found that wolves outperformed dogs in finding food caches, likely due to a "difference in motivation" between wolves and dogs.[116] Some puppies and dogs engage in coprophagy out of habit, stress, for attention, or boredom; most of them will not do it later in life. A study hypothesizes that the behavior was inherited from wolves, a behavior likely evolved to lessen the presence of intestinal parasites in dens.[117]

Most dogs can swim. In a study of 412 dogs, around 36.5% of the dogs could not swim; the other 63.5% were able to swim without a trainer in a swimming pool.[118] A study of 55 dogs found a correlation between swimming and 'improvement' of the hip osteoarthritis joint.[119]

Nursing

The female dog may produce colostrum, a type of milk high in nutrients and antibodies, 1–7 days before giving birth. Milk production lasts for around three months,[120][121] and increases with litter size.[121] The dog can sometimes vomit and refuse food during child contractions.[122] In the later stages of the dog's pregnancy, nesting behaviour may occur.[123] Puppies are born with a protective fetal membrane that the mother usually removes shortly after birth. Dogs can have the maternal instincts to start grooming their puppies, consume their puppies' feces, and protect their puppies, likely due to their hormonal state.[124][125] While male-parent dogs can show more disinterested behaviour toward their own puppies,[126] most can play with the young pups as they would with other dogs or humans.[127] A female dog may abandon or attack her puppies or her male partner dog if she is stressed or in pain.[128]

Intelligence

Researchers have tested dogs' ability to perceive information, retain it as knowledge, and apply it to solve problems. Studies of two dogs suggest that dogs can learn by inference. A study with Rico, a Border Collie, showed that he knew the labels of over 200 different items. He inferred the names of novel things by exclusion learning and correctly retrieved those new items after four weeks of the initial exposure. A study of another Border Collie, Chaser, documented that he had learned the names and could associate them by verbal command with over 1,000 words.[129]

One study of canine cognitive abilities found that dogs' capabilities are similar to those of horses, chimpanzees, or cats.[130] One study of 18 household dogs found that the dogs could not distinguish food bowls at specific locations without distinguishing cues; the study stated that this indicates a lack of spatial memory.[131] A study stated that dogs have a visual sense for number. The dogs showed a ratio-dependent activation both for numerical values from 1–3 to larger than four.[132]

Dogs demonstrate a theory of mind by engaging in deception.[133] Another experimental study showed evidence that Australian dingos can outperform domestic dogs in non-social problem-solving, indicating that domestic dogs may have lost much of their original problem-solving abilities once they joined humans.[134] Another study showed that dogs stared at humans after failing to complete an impossible version of the same task they had been trained to solve. Wolves, under the same situation, avoided staring at humans altogether.[135]

Communication

Dog communication is the transfer of information between dogs, as well as between dogs and humans.[136] Communication behaviors of dogs include eye gaze, facial expression,[137][138] vocalization, body posture (including movements of bodies and limbs), and gustatory communication (scents, pheromones, and taste). Dogs mark their territories by urinating on them, which is more likely when entering a new environment.[139][140] Both sexes of dogs may also urinate to communicate anxiety or frustration, submissiveness, or when in exciting or relaxing situations.[141] Aroused dogs can be a result of the dogs' higher cortisol levels.[142] Between 3 and 8 weeks of age, dogs tend to focus on other dogs for social interaction, and between 5 and 12 weeks of age, they shift their focus to people.[143] Belly exposure in dogs can be a defensive behavior that can lead to a bite or to seek comfort.[144]

Humans communicate with dogs by using vocalization, hand signals, and body posture. With their acute sense of hearing, dogs rely on the auditory aspect of communication for understanding and responding to various cues, including the distinctive barking patterns that convey different messages. A study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has shown that dogs respond to both vocal and nonvocal voices using the brain's region towards the temporal pole, similar to that of humans' brains. Most dogs also looked significantly longer at the face whose expression matched the valence of vocalization.[145][146][147] A study of caudate responses shows that dogs tend to respond more positively to social rewards than to food rewards.[148]

Ecology

Population

The dog is probably the most widely abundant large carnivoran living in the human environment.[149][150] In 2020, the estimated global dog population was between 700 million and 1 billion.[151] In the same year, a study found the dog to be the most popular pet in the United States; there is a dog in 34 out of every 100 homes.[7] About 20% of dogs live as pets in developed countries.[152] In the developing world, it is estimated that three-quarters of the world's dog population lives in the developing world as feral, village, or community dogs.[153] Most of these dogs live as scavengers and have never been owned by humans, with one study showing that village dogs' most common response when approached by strangers is to run away (52%) or respond aggressively (11%).[154]

Competitors

Feral and free-ranging dogs' potential to compete with other large carnivores is limited by their strong association with humans.[149] Although wolves are known to kill dogs, they tend to live in pairs in areas where they are highly persecuted, giving them a disadvantage when facing large dog groups.[155][156] In some instances, wolves have displayed an uncharacteristic fearlessness of humans and buildings when attacking dogs, to the extent that they have to be beaten off or killed.[157] Although the numbers of dogs killed each year are relatively low, it induces a fear of wolves entering villages and farmyards to take dogs, and losses of dogs to wolves have led to demands for more liberal wolf hunting regulations.[155]

Coyotes and big cats have also been known to attack dogs. In particular, leopards are known to have a preference for dogs and have been recorded to kill and consume them, no matter their size.[158] Siberian tigers in the Amur river region have killed dogs in the middle of villages. Amur tigers will not tolerate wolves as competitors within their territories, and the tigers could be considering dogs in the same way.[159] Striped hyenas are known to kill dogs in their range.[160]

Dogs as introduced predator mammals have affected the ecology of New Zealand, which lacked indigenous land-based mammals before human settlement.[161] Dogs have made 11 vertebrate species extinct and are identified as a 'potential threat' to at least 188 threatened species worldwide;[162] another figure is that dogs have also been linked to the extinction of 156 animal species.[163] Dogs have been documented to have killed a few birds of the endangered species, the kagu, in New Caledonia.[164]

Diet

Dogs are typically described as omnivores.[5][165][166] Compared to wolves, dogs from agricultural societies have extra copies of amylase and other genes involved in starch digestion that contribute to an increased ability to thrive on a starch-rich diet.[4] Similar to humans, some dog breeds produce amylase in their saliva and are classified as having a high-starch diet.[167] Despite being an omnivore, dogs are only able to produce bile acid with taurine. They must get their intake of vitamin D from consuming other animals.[168]

Of the twenty-one amino acids common to all life forms (including selenocysteine), dogs cannot synthesize ten: arginine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine.[169][170][171] Like cats, dogs require arginine to maintain nitrogen balance. These nutritional requirements place dogs halfway between carnivores and omnivores.[172]

Range

As a domesticated or semi-domesticated animal, the dog has notable exceptions of presence in:

- The Aboriginal Tasmanians, who were separated from Australia before the arrival of dingos on that continent[173]

- The Andamanese peoples, who were isolated when rising sea levels covered the land bridge to Myanmar[174][175]

- The Fuegians, who instead domesticated the Fuegian dog, an already extinct different canid species[176]

- Individual Pacific islands whose maritime settlers did not bring dogs or where the dogs died out after original settlement, notably the Mariana Islands,[177] Palau[178] and most of the Caroline Islands with exceptions such as Fais Island and Nukuoro,[179] the Marshall Islands,[180] the Gilbert Islands,[180] New Caledonia,[181] Vanuatu,[181][182] Tonga,[182] Marquesas,[182] Mangaia in the Cook Islands, Rapa Iti in French Polynesia, Easter Island,[182] the Chatham Islands,[183] and Pitcairn Island (settled by the Bounty mutineers, who killed off their dogs to escape discovery by passing ships).[184]

Dogs were introduced to Antarctica as sled dogs. Starting practice in December 1993, dogs were later outlawed by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty international agreement due to the possible risk of spreading infections.[185]

Dogs shall not be introduced onto land, ice shelves or sea ice.

— Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1991 in Madrid, amended version of Annex II, Article 4 (number two)

Roles with humans

The domesticated dog originated as a predator and scavenger.[186][187] They inherited complex behaviors, such as bite inhibition, from their wolf ancestors, which would have been pack hunters with complex body language. These sophisticated forms of social cognition and communication may account for dogs' trainability, playfulness, and ability to fit into human households and social situations,[188] and probably also their co-existence with early human hunter-gatherers.[189][190]

Dogs perform many roles for people, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and the military, companionship, and aiding disabled individuals. These roles in human society have earned them the nickname "man's best friend" in the Western world. In some cultures, however, dogs are also a source of meat.[191][192]

Pets

The keeping of dogs as companions, particularly by elites, has a long history.[193] Pet-dog populations grew significantly after World War II as suburbanization increased.[193] In the 1980s, there have been changes in the pet dog's functions, such as the increased role of dogs in the emotional support of their human guardians.[194][195][196] Within the second half of the 20th century, more and more dog owners considered their animal to be a part of the family. This major social status shift allowed the dog to conform to social expectations of personality and behavior.[196] The second has been the broadening of the concepts of family and the home to include dogs-as-dogs within everyday routines and practices.[196]

Products such as dog-training books, classes, and television programs, target dog owners.[197][198] The majority of contemporary dog-owners describe their pet as part of the family, although some state that it is an ambivalent relationship.[196] Some dog-trainers have promoted a dominance model of dog-human relationships. However, the idea of the "alpha dog" trying to be dominant is based on a controversial theory about wolf packs.[199][200] It has been disputed that "trying to achieve status" is characteristic of dog-human interactions.[201] Human family members have increased participation in activities in which the dog is an integral partner, such as dog dancing and dog yoga.[197]

According to statistics published by the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association in the National Pet Owner Survey in 2009–2010, an estimated 77.5 million people in the United States have pet dogs.[202] The source shows that nearly 40% of American households own at least one dog, of which 67% own just one dog, 25% own two dogs, and nearly 9% own more than two dogs. The data also shows an equal number of male and female pet dogs; less than one-fifth of the owned dogs come from shelters.[203]

Workers

In addition to dogs' role as companion animals, dogs have been bred for herding livestock (such as collies and sheepdogs); for hunting; for rodent control (such as terriers); as search and rescue dogs;[204][205] as detection dogs (such as those trained to detect illicit drugs or chemical weapons);[206][207] as homeguard dogs; as police dogs (sometimes nicknamed "K-9"); as welfare-purpose dogs; as dogs who assist fishermen retrieve their nets; and as dogs that pull loads (such as sled dogs).[5] In 1957, the dog Laika became one of the first animals to be launched into Earth orbit aboard the Soviets's Sputnik 2; Laika died during the flight from overheating.[208][209]

Various kinds of service dogs and assistance dogs, including guide dogs, hearing dogs, mobility assistance dogs, and psychiatric service dogs, assist individuals with disabilities.[210][211] A study of 29 dogs found that 9 dogs owned by people with epilepsy were reported to exhibit attention-getting behavior to their handler 30 seconds to 45 minutes prior to an impending seizure; there was no significant correlation between the patients' demographics, health, or attitude towards their pets.[212]

Shows and sports

Dogs compete in breed-conformation shows and dog sports (including racing, sledding, and agility competitions). In dog shows, also referred to as "breed shows", a judge familiar with the specific dog breed evaluates individual purebred dogs for conformity with their established breed type as described in a breed standard.[213] Weight pulling, a dog sport involving pulling weight, has been criticized for promoting doping and for its risk of injury.[214]

Dogs as food

Humans have consumed dog meat going back at least 14,000 years. It's unknown to what extent prehistoric dogs were consumed and bred for meat. For centuries, the practice was prevalent in Southeast Asia, East Asia, Africa, and Oceania before cultural changes triggered by the spread of religions resulted in dog meat consumption declining and becoming more taboo.[215] Switzerland, Polynesia, and pre-Columbian Mexico historically consumed dog meat.[216][217][218] Some Native American dogs, like the Peruvian Hairless Dog and Xoloitzcuintle, were raised to be sacrificed and eaten.[219][220] Han Chinese traditionally ate dogs.[221] Consumption of dog meat declined but did not end during the Sui dynasty (581–618) and Tang dynasty (618–907) due in part to the spread of Buddhism and the upper class rejecting the practice.[222][223] Dog consumption was rare in India, Iran, and Europe.[215]

Eating dog meat is a social taboo in most parts of the world,[224] though some still consume it in modern times.[225][226] It is still consumed in some East Asian countries, including China,[191] Vietnam,[192] Korea,[227] Indonesia,[228] and the Philippines.[229] An estimated 30 million dogs are killed and consumed in Asia every year.[221] China is the world's largest consumer of dogs, with an estimated 10 to 20 million dogs killed every year for human consumption.[230] In Vietnam, about 5 million dogs are slaughtered annually.[231] In 2024, China, Singapore, and Thailand placed a ban on the consumption of dogs within their borders.[232] In some parts of Poland[233][234] and Central Asia,[235][236] dog fat is reportedly believed to be beneficial for the lungs.[237] Proponents of eating dog meat have argued that placing a distinction between livestock and dogs is Western hypocrisy and that there is no difference in eating different animals' meat.[238][239][240][241]

There is a long history of dog meat consumption in South Korea, but the practice has fallen out of favor.[242] A 2017 survey found that under 40% of participants supported a ban on the distribution and consumption of dog meat. This increased to over 50% in 2020, suggesting changing attitudes, particularly among younger individuals.[9] In 2018, the South Korean government passed a bill banning restaurants that sell dog meat from doing so during that year's Winter Olympics.[243] On 9 January 2024, the South Korean parliament passed a law banning the distribution and sale of dog meat. It will take effect in 2027, with plans to assist dog farmers in transitioning to other products.[244] The primary type of dog raised for meat in South Korea has been the Nureongi.[245] In North Korea where meat is scarce, eating dog is a common and accepted practice, officially promoted by the government.[246][247]

Health risks

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 59,000 people died globally from rabies, with 59.6% of the deaths in Asia and 36.4% in Africa. Rabies is a disease for which dogs are the most significant vector.[248] Dog bites affect tens of millions of people globally each year.[249] The primary victims of dog bite incidents are children. They are more likely to sustain more serious injuries from bites, which can lead to death.[249] Sharp claws can lacerate flesh and cause serious infections.[250] In the United States, cats and dogs are a factor in more than 86,000 falls each year.[251] It has been estimated that around 2% of dog-related injuries treated in U.K. hospitals are domestic accidents. The same study concluded that dog-associated road accidents involving injuries more commonly involve two-wheeled vehicles.[252] Some countries and cities have also banned or restricted certain dog breeds, usually for safety concerns.[253]

Toxocara canis (dog roundworm) eggs in dog feces can cause toxocariasis. In the United States, about 10,000 cases of Toxocara infection are reported in humans each year, and almost 14% of the U.S. population is infected.[254] Untreated toxocariasis can cause retinal damage and decreased vision.[255] Dog feces can also contain hookworms that cause cutaneous larva migrans in humans.[256][257]

Health benefits

The scientific evidence is mixed as to whether a dog's companionship can enhance human physical and psychological well-being.[258] Studies suggest that there are benefits to physical health and psychological well-being, but they have been criticized for being "poorly controlled".[259][260] One study states that "the health of elderly people is related to their health habits and social supports but not to their ownership of, or attachment to, a companion animal".[261] Earlier studies have shown that pet-dog or -cat guardians make fewer hospital visits and are less likely to be on medication for heart problems and sleeping difficulties than non-guardians.[261] People with pet dogs took considerably more physical exercise than those with cats or those without pets; these effects are relatively long-term.[262] Pet guardianship has also been associated with increased survival in cases of coronary artery disease. Human guardians are significantly less likely to die within one year of an acute myocardial infarction than those who do not own dogs.[263] Studies have found a small to moderate correlation between dog-ownership and increased adult physical-activity levels.[264]

A 2005 paper states:[258]

recent research has failed to support earlier findings that pet ownership is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, a reduced use of general practitioner services, or any psychological or physical benefits on health for community dwelling older people. Research has, however, pointed to significantly less absenteeism from school through sickness among children who live with pets.

Health benefits of dogs can result from contact with dogs in general, not solely from having dogs as pets. For example, when in a pet dog's presence, people show reductions in cardiovascular, behavioral, and psychological indicators of anxiety[265] and are exposed to immune-stimulating microorganisms, which can protect against allergies and autoimmune diseases (according to the hygiene hypothesis). Other benefits include dogs as social support.[266]

One study indicated that wheelchair-users experience more positive social interactions with strangers when accompanied by a dog than when they are not.[267] In a 2015 study, it was found that having a pet made people more inclined to foster positive relationships with their neighbors.[268] In one study, new guardians reported a significant reduction in minor health problems during the first month following pet acquisition, which was sustained through the 10-month study.[262]

Using dogs and other animals as a part of therapy dates back to the late-18th century, when animals were introduced into mental institutions to help socialize patients with mental disorders.[269] Animal-assisted intervention research has shown that animal-assisted therapy with a dog can increase smiling and laughing among people with Alzheimer's disease.[270] One study demonstrated that children with ADHD and conduct disorders who participated in an education program with dogs and other animals showed increased attendance, knowledge, and skill-objectives and decreased antisocial and violent behavior compared with those not in an animal-assisted program.[271]

Cultural importance

Artworks have depicted dogs as symbols of guidance, protection, loyalty, fidelity, faithfulness, alertness, and love.[272] In ancient Mesopotamia, from the Old Babylonian period until the Neo-Babylonian period, dogs were the symbol of Ninisina, the goddess of healing and medicine,[273] and her worshippers frequently dedicated small models of seated dogs to her.[273] In the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, dogs served as emblems of magical protection.[273] In China, Korea, and Japan, dogs are viewed as kind protectors.[274]

In mythology, dogs often appear as pets or as watchdogs.[274] Stories of dogs guarding the gates of the underworld recur throughout Indo-European mythologies[275][276] and may originate from Proto-Indo-European traditions.[275][276] In Greek mythology, Cerberus is a three-headed, dragon-tailed watchdog who guards the gates of Hades.[274] Dogs also feature in association with the Greek goddess Hecate.[277] In Norse mythology, a dog called Garmr guards Hel, a realm of the dead.[274] In Persian mythology, two four-eyed dogs guard the Chinvat Bridge.[274] In Welsh mythology, Cŵn Annwn guards Annwn.[274] In Hindu mythology, Yama, the god of death, owns two watchdogs named Shyama and Sharvara, which each have four eyes—they are said to watch over the gates of Naraka.[278] A black dog is considered to be the vahana (vehicle) of Bhairava (an incarnation of Shiva).[279]

In Christianity, dogs represent faithfulness.[274] Within the Roman Catholic denomination specifically, the iconography of Saint Dominic includes a dog after the saint's mother dreamt of a dog springing from her womb and became pregnant shortly after that.[280] As such, the Dominican Order (Ecclesiastical Latin: Domini canis) means "dog of the Lord" or "hound of the Lord".[280] In Christian folklore, a church grim often takes the form of a black dog to guard Christian churches and their churchyards from sacrilege.[281] Jewish law does not prohibit keeping dogs and other pets but requires Jews to feed dogs (and other animals that they own) before themselves and to make arrangements for feeding them before obtaining them.[282][283] The view on dogs in Islam is mixed, with some schools of thought viewing them as unclean,[274] although Khaled Abou El Fadl states that this view is based on "pre-Islamic Arab mythology" and "a tradition [...] falsely attributed to the Prophet".[284] The Sunni Maliki school jurists disagree with the idea that dogs are unclean.[285]

Terminology

- Dog – the species (or subspecies) as a whole, also any male member of the same.[286]

- Bitch – any female member of the species (or subspecies).[287]

- Puppy or pup – a young member of the species (or subspecies) under 12 months old.[288]

- Sire – the male parent of a litter.[288]

- Dam – the female parent of a litter.[288]

- Litter – all of the puppies resulting from a single whelping.[288]

- Whelping – the act of a bitch giving birth.[288]

- Whelps – puppies still dependent upon their dam.[288]

References

- ^ a b c Thalmann O, Perri AR (2018). "Paleogenomic Inferences of Dog Domestication". In Lindqvist C, Rajora O (eds.). Paleogenomics. Population Genomics. Springer, Cham. pp. 273–306. doi:10.1007/13836_2018_27. ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8.

- ^ a b Linnæus C (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10 ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. pp. 38–40. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b Wozencraft WC (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson DE, Reeder DM (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. (via Google Books) Archived 14 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Axelsson E, Ratnakumar A, Arendt ML, Maqbool K, Webster MT, Perloski M, et al. (March 2013). "The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet". Nature (Journal). 495 (7441): 360–364. Bibcode:2013Natur.495..360A. doi:10.1038/nature11837. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23354050. S2CID 4415412.

- ^ a b c d e Dewey, T. and S. Bhagat. 2002. "Canis lupus familiaris". Archived 26 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Koepfli KP, Pollinger J, Godinho R, Robinson J, Lea A, Hendricks S, et al. (August 2015). "Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species". Current Biology. 25 (16): 2158–2165. Bibcode:2015CBio...25.2158K. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Freedman AH, Wayne RK (February 2017). "Deciphering the Origin of Dogs: From Fossils to Genomes". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 281–307. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110937. PMID 27912242.

- ^ a b Thiele K (19 April 2019). "The Trouble With Dingoes". Taxonomy Australia. Australian Academy of Science.

- ^ a b Perri AR, Feuerborn TR, Frantz LA, Larson G, Malhi RS, Meltzer DJ, et al. (9 February 2021). "Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (6). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11810083P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2010083118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8017920. PMID 33495362.

- ^ "Dogs domesticated before farming". Nature. 505 (7485): 589–589. January 2014. doi:10.1038/505589e. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Shao-jie Zhang, Guo-Dong Wang, Pengcheng Ma, Liang-liang Zhang (2020). "Genomic regions under selection in the feralization of the dingoes". Nature Communications. 11 (671): 671. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11..671Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14515-6. PMC 6997406. PMID 32015346.

- ^ Cairns KM, Wilton AN (17 September 2016). "New insights on the history of canids in Oceania based on mitochondrial and nuclear data". Genetica. 144 (5): 553–565. doi:10.1007/s10709-016-9924-z. PMID 27640201.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, p. 58.

- ^ Clutton-Brock J (1995). "2-Origins of the dog". In Serpell J (ed.). The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–20. ISBN 978-0-521-41529-3.

- ^ Donfrancesco V, Allen BL, Appleby R, Behrendorff L, Conroy G, Crowther MS, et al. (March 2023). "Understanding conflict among experts working on controversial species: A case study on the Australian dingo". Conservation Science and Practice. 5 (3). Bibcode:2023ConSP...5E2900D. doi:10.1111/csp2.12900. ISSN 2578-4854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Boronyak L, Jacobs B, Smith B (May 2023). "Unlocking Lethal Dingo Management in Australia". Diversity. 15 (5): 642. doi:10.3390/d15050642.

- ^ Alvares F, Bogdanowicz W, Campbell LA, Godinho R, Hatlauf J, Jhala YV, et al. (2019). "Old World Canis spp. with taxonomic ambiguity: Workshop conclusions and recommendations. CIBIO. Vairão, Portugal, 28th – 30th May 2019" (PDF). IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Perri AR, Feuerborn TR, Frantz LA, Larson G, Malhi RS, Meltzer DJ, et al. (9 February 2021). "Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (6). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11810083P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2010083118. PMC 8017920. PMID 33495362.

- ^ Janssens L, Giemsch L, Schmitz R, Street M, Van Dongen S, Crombé P (April 2018). "A new look at an old dog: Bonn-Oberkassel reconsidered". Journal of Archaeological Science. 92: 126–138. Bibcode:2018JArSc..92..126J. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.01.004. hdl:1854/LU-8550758. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b Larson G, Bradley DG (16 January 2014). "How Much Is That in Dog Years? The Advent of Canine Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics. 10 (1): e1004093. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004093. PMC 3894154. PMID 24453989.

- ^ a b c d e f Freedman AH, Wayne RK (2017). "Deciphering the Origin of Dogs: From Fossils to Genomes". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 281–307. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110937. PMID 27912242. S2CID 26721918.

- ^ a b c Frantz LA, Bradley DG, Larson G, Orlando L (August 2020). "Animal domestication in the era of ancient genomics" (PDF). Nature Reviews Genetics. 21 (8): 449–460. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0225-0. PMID 32265525. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ a b Irving-Pease EK, Ryan H, Jamieson A, Dimopoulos EA, Larson G, Frantz LA (2018). "Paleogenomics of Animal Domestication". Paleogenomics. Population Genomics. pp. 225–272. doi:10.1007/13836_2018_55. ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Bergström A, Frantz L, Schmidt R, Ersmark E, Lebrasseur O, Girdland-Flink L, et al. (2020). "Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs". Science. 370 (6516): 557–564. doi:10.1126/science.aba9572. PMC 7116352. PMID 33122379. S2CID 225956269.

- ^ Gojobori J, Arakawa N, Xiaokaiti X, Matsumoto Y, Matsumura S, Hongo H, et al. (23 February 2024). "Japanese wolves are most closely related to dogs and share DNA with East Eurasian dogs". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 1680. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.1680G. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46124-y. PMC 10891106. PMID 38396028.

- ^ Larson G (2012). "Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography". PNAS. 109 (23): 8878–8883. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8878L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203005109. PMC 3384140. PMID 22615366.

- ^ a b c d e Ostrander EA, Wang GD, Larson G, vonHoldt BM, Davis BW, Jagannathan V, et al. (1 July 2019). "Dog10K: an international sequencing effort to advance studies of canine domestication, phenotypes and health". National Science Review. 6 (4): 810–824. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwz049. PMC 6776107. PMID 31598383.

- ^ Gojobori J, Arakawa N, Xiaokaiti X, Matsumoto Y, Matsumura S, Hongo H, et al. (23 February 2024). "Japanese wolves are most closely related to dogs and share DNA with East Eurasian dogs". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 1680. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.1680G. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46124-y. PMC 10891106. PMID 38396028.

- ^ Pendleton AL, Shen F, Taravella AM, Emery S, Veeramah KR, Boyko AR, et al. (December 2018). "Comparison of village dog and wolf genomes highlights the role of the neural crest in dog domestication". BMC Biology. 16 (1): 64. doi:10.1186/s12915-018-0535-2. ISSN 1741-7007. PMC 6022502. PMID 29950181.

- ^ Parker HG, Dreger DL, Rimbault M, Davis BW, Mullen AB, Carpintero-Ramirez G, et al. (2017). "Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development". Cell Reports. 19 (4): 697–708. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.079. PMC 5492993. PMID 28445722.

- ^ "Great Dane | Description, Temperament, Lifespan, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Chihuahua dog | Description, Temperament, Images, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. 29 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Cunliffe (2004), p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Fogle (2009), pp. 38–39.

- ^ "Back pain". Elwood vet. Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b Jones & Hamilton (1971), p. 27.

- ^ a b DK (6 July 2023). The Dog Encyclopedia: The Definitive Visual Guide. Dorling Kindersley Limited. pp. 15–19. ISBN 978-0-241-63310-6.

- ^ Nießner C, Denzau S, Malkemper EP, Gross JC, Burda H, Winklhofer M, et al. (2016). "Cryptochrome 1 in Retinal Cone Photoreceptors Suggests a Novel Functional Role in Mammals". Scientific Reports. 6: 21848. Bibcode:2016NatSR...621848N. doi:10.1038/srep21848. PMC 4761878. PMID 26898837.

- ^ Hart V, Nováková P, Malkemper EP, Begall S, Hanzal V, Ježek M, et al. (December 2013). "Dogs are sensitive to small variations of the Earth's magnetic field". Frontiers in Zoology. 10 (1): 80. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-10-80. PMC 3882779. PMID 24370002.

- ^ Byosiere SE, Chouinard PA, Howell TJ, Bennett PC (1 October 2018). "What do dogs (Canis familiaris) see? A review of vision in dogs and implications for cognition research". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 25 (5): 1798–1813. doi:10.3758/s13423-017-1404-7. ISSN 1531-5320. PMID 29143248.

- ^ Siniscalchi M, d'Ingeo S, Fornelli S, Quaranta A (8 November 2017). "Are dogs red–green colour blind?". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (11): 170869. doi:10.1098/rsos.170869. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5717654. PMID 29291080.

- ^ Miller PE, Murphy CJ (15 December 1995). "Vision in dogs". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 207 (12): 1623–1634. doi:10.2460/javma.1995.207.12.1623.

- ^ updated NW (4 February 2022). "How Do Dogs See the World?". livescience.com. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Eye Structure and Function in Dogs - Dog Owners". MSD Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Pongrácz P, Ujvári V, Faragó T, Miklósi Á, Péter A (1 July 2017). "Do you see what I see? The difference between dog and human visual perception may affect the outcome of experiments". Behavioural Processes. 140: 53–60. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.04.002. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 28396145.

- ^ Coren S (2004). How dogs think : understanding the canine mind. Internet Archive. New York : Free Press. pp. 50–81. ISBN 978-0-7432-2232-7.

- ^ Kokocińska-Kusiak A, Woszczyło M, Zybala M, Maciocha J, Barłowska K, Dzięcioł M (August 2021). "Canine Olfaction: Physiology, Behavior, and Possibilities for Practical Applications". Animals. 11 (8): 2463. doi:10.3390/ani11082463. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 8388720. PMID 34438920.

- ^ Barber AL, Wilkinson A, Montealegre-Z F, Ratcliffe VF, Guo K, Mills DS (2020). "A comparison of hearing and auditory functioning between dogs and humans". Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews. 15: 45–94. doi:10.3819/CCBR.2020.150007.

- ^ "Dog Senses - A Dog's Sense of Touch Compared to Humans | Puppy And Dog Care". 24 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ Cunliffe (2004), pp. 22–23.

- ^ King C, Smith TJ, Grandin T, Borchelt P (2016). "Anxiety and impulsivity: Factors associated with premature graying in young dogs". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 185: 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2016.09.013.

- ^ Ciucci P, Lucchini V, Boitani L, Randi E (December 2003). "Dewclaws in wolves as evidence of admixed ancestry with dogs". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 81 (12): 2077–2081. Bibcode:2003CaJZ...81.2077C. doi:10.1139/z03-183.

- ^ Amici F, Meacci S, Caray E, Oña L, Liebal K, Ciucci P (2024). "A first exploratory comparison of the behaviour of wolves (Canis lupus) and wolf-dog hybrids in captivity". Animal Cognition. 27 (1): 9. doi:10.1007/s10071-024-01849-7. PMC 10907477. PMID 38429445.

- ^ "Study explores the mystery of why dogs wag their tails". Earth.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Wada N, Hori H, Tokuriki M (July 1993). "Electromyographic and kinematic studies of tail movements in dogs during treadmill locomotion". Journal of Morphology. 217 (1): 105–113. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052170109. ISSN 0362-2525. PMID 8411184.

- ^ "Stud Tail Tail Gland Hyperplasia in Dogs". VCA Animal Hospitals. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Siniscalchi M, Lusito R, Vallortigara G, Quaranta A (31 October 2013). "Seeing Left- or Right-Asymmetric Tail Wagging Produces Different Emotional Responses in Dogs". Current Biology. 23 (22). Cell Press: 2279–2282. Bibcode:2013CBio...23.2279S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.027. PMID 24184108.

- ^ Artelle KA, Dumoulin LK, Reimchen TE (19 January 2010). "Behavioural responses of dogs to asymmetrical tail wagging of a robotic dog replica". Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition. 16 (2). Financially supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada: 129–135. doi:10.1080/13576500903386700. PMID 20087813.

- ^ "What is Happy Tail Syndrome in Dogs?". thewildest.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Paw Print Genetics - T Locus (Natural Bobtail) in the Poodle". pawprintgenetics.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Ear cropping and tail docking of dogs". American Veterinary Medical Association. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Tail docking in dogs". British Veterinary Association. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Diesel G, Pfeiffer D, Crispin S, Brodbelt D (26 June 2010). "Risk factors for tail injuries in dogs in Great Britain". Veterinary Record. 166 (26): 812–817. doi:10.1136/vr.b4880. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 20581358. Archived from the original on 14 July 2024. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Gear R (2020). "Medical disorders of dogs and cats and their nursing". In Cooper B, Mullineaux E, Turner L (eds.). BSAVA Textbook of Veterinary Nursing. British Small Animal Veterinary Association. pp. 532–597.

- ^ Fisher M, McGarry J (2020). "Principles of parasitology". In Cooper B, Mullineaux E, Turner L (eds.). BSAVA Textbook of Veterinary Nursing. British Small Animal Veterinary Association. pp. 149–171.

- ^ "Rabies facts". World Health Organisation.

- ^ a b c Dawson S, Cooper B (2020). "Principles of infection and immunity". In Cooper B, Mullineaux E, Turner L (eds.). BSAVA Textbook of Veterinary Nursing. British Small Animal Veterinary Association. pp. 172–186.

- ^ Wismer T (1 December 2013). "ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center Toxin Exposures for Pets". In Bonagura JD, Twedt DC (eds.). Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy (15th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 92. ISBN 9780323227629.

- ^ Welch S, Almgren C (1 December 2013). "Toxin Exposures in Small Animals". In Bonagura JD, Twedt DC (eds.). Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy (15th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 93–96. ISBN 9780323227629.

- ^ Fleming JM, Creevy KE, Promislow DE (2011). "Mortality in North American Dogs from 1984 to 2004: An Investigation into Age-, Size-, and Breed-Related Causes of Death". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 25 (2): 187–198. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0695.x. ISSN 0891-6640. PMID 21352376.

- ^ Roccaro M, Salini R, Pietra M, Sgorbini M, Gori E, Dondi M, et al. (2024). "Factors related to longevity and mortality of dogs in Italy". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 225. Elsevier BV: 106155. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2024.106155. hdl:11585/961937. ISSN 0167-5877. PMID 38394961.

- ^ a b Lewis TW, Wiles BM, Llewellyn-Zaidi AM, Evans KM, O'Neill DG (17 October 2018). "Longevity and mortality in Kennel Club registered dog breeds in the UK in 2014". Canine Genetics and Epidemiology. 5 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 10. doi:10.1186/s40575-018-0066-8. ISSN 2052-6687. PMC 6191922. PMID 30349728.

- ^ Feldman EC, Nelson RW, Reusch C, Scott-Moncrieff JC (8 December 2014). Canine and Feline Endocrinology. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders. pp. 44–49. ISBN 978-1-4557-4456-5.

- ^ a b Montoya M, Morrison JA, Arrignon F, Spofford N, Charles H, Hours MA, et al. (21 February 2023). "Life expectancy tables for dogs and cats derived from clinical data". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 10. doi:10.3389/fvets.2023.1082102. PMC 9989186. PMID 36896289.

- ^ McMillan KM, Bielby J, Williams CL, Upjohn MM, Casey RA, Christley RM (February 2024). "Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 531. Bibcode:2024NatSR..14..531M. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w. PMC 10834484. PMID 38302530.

- ^ McMillan KM, Bielby J, Williams CL, Upjohn MM, Casey RA, Christley RM (1 February 2024). "Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 531. Bibcode:2024NatSR..14..531M. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10834484. PMID 38302530.

- ^ Mata F, Mata A (19 July 2023). "Investigating the relationship between inbreeding and life expectancy in dogs: mongrels live longer than pure breeds". PeerJ. 11: e15718. doi:10.7717/peerj.15718. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 10362839. PMID 37483958.

- ^ Nurse A (2 February 2024). "How long might your dog live? New study calculates life expectancy for different breeds". The Conversation. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Paul M, Sen Majumder S, Sau S, Nandi AK, Bhadra A (25 January 2016). "High early life mortality in free-ranging dogs is largely influenced by humans". Scientific Reports. 6: 19641. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619641P. doi:10.1038/srep19641. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4726281. PMID 26804633.

- ^ "Would dogs survive without humans? The answer may surprise you". ABC News. 6 January 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Ma K (July 2018). "Estrous Cycle Manipulation in Dogs". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice. 48 (4): 581–594. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.02.006. ISSN 1878-1306. PMID 29709316.

- ^ Da Costa RE, Kinsman RH, Owczarczak-Garstecka SC, Casey RA, Tasker S, Knowles TG, et al. (July 2022). "Age of sexual maturity and factors associated with neutering dogs in the UK and the Republic of Ireland". Veterinary Record. 191 (6): e1265. doi:10.1002/vetr.1265. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 34939683.

- ^ "Estrus and Mating in Dogs". VCA Animal Hospitals. Archived from the original on 7 February 2024. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Concannon P, Tsutsui T, Shille V (2001). "Embryo development, hormonal requirements and maternal responses during canine pregnancy". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. Supplement. 57: 169–179. PMID 11787146.

- ^ "Dog Development – Embryology". Php.med.unsw.edu.au. 16 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Gestation in dogs". Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "HSUS Pet Overpopulation Estimates". The Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Heidenberger E, Unshelm J (February 1990). "Verhaltensänderungen von Hunden nach Kastration" [Changes in the behavior of dogs after castration]. Tierarztliche Praxis (in German). 18 (1): 69–75. PMID 2326799.

- ^ Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.). Williams and Wilkins. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-683-06105-5.

- ^ Arnold S (1997). "Harninkontinenz bei kastrierten Hündinnen. Teil 1: Bedeutung, Klinik und Ätiopathogenese" [Urinary incontinence in castrated bitches. Part 1: Significance, clinical aspects and etiopathogenesis]. Schweizer Archiv Fur Tierheilkunde (in German). 139 (6): 271–276. PMID 9411733.

- ^ Johnston S, Kamolpatana K, Root-Kustritz M, Johnston G (July 2000). "Prostatic disorders in the dog". Animal Reproduction Science. 60–61: 405–415. doi:10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00101-9. PMID 10844211.

- ^ Kustritz MV (December 2007). "Determining the optimal age for gonadectomy of dogs and cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 231 (11): 1665–1675. doi:10.2460/javma.231.11.1665. PMID 18052800.

- ^ a b c Kutzler MA (1 December 2013). "Early Age Neutering in Dogs and Cats". In Bonagura JD, Twedt DC (eds.). Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy (15th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 982–984. ISBN 9780323227629.

- ^ "Top 10 reasons to spay/neuter your pet". American Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ Hart BL, Hart LA, Thigpen AP, Willits NH (14 July 2014). "Long-Term Health Effects of Neutering Dogs: Comparison of Labrador Retrievers with Golden Retrievers". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e102241. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j2241H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102241. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4096726. PMID 25020045.

- ^ Fossati P (31 May 2022). "Spay/neuter laws as a debated approach to stabilizing the populations of dogs and cats: An overview of the European legal framework and remarks". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 27 (2). Informa UK Limited: 281–293. doi:10.1080/10888705.2022.2081807. ISSN 1088-8705. PMID 35642302.

- ^ Leroy G (2011). "Genetic diversity, inbreeding and breeding practices in dogs: results from pedigree analyses". Vet. J. 189 (2): 177–182. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.06.016. PMID 21737321.

- ^ Leroy G, Phocas F, Hedan B, Verrier E, Rognon X (January 2015). "Inbreeding impact on litter size and survival in selected canine breeds" (PDF). The Veterinary Journal. 203 (1): 74–78. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.11.008. PMID 25475165. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Gresky C, Hamann H, Distl O (2005). "Einfluss von Inzucht auf die Wurfgröße und den Anteil tot geborener Welpen beim Dackel" [Influence of inbreeding on litter size and the proportion of stillborn puppies in dachshunds]. Berliner und Munchener Tierarztliche Wochenschrift (in German). 118 (3–4): 134–139. PMID 15803761. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ van der Beek S, Nielen AL, Schukken YH, Brascamp EW (September 1999). "Evaluation of genetic, common-litter, and within-litter effects on preweaning mortality in a birth cohort of puppies". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 60 (9): 1106–1110. doi:10.2460/ajvr.1999.60.09.1106. PMID 10490080.

- ^ Levitis DA, Lidicker WZ, Freund G (July 2009). "Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 78 (1): 103–110. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018. PMC 2760923. PMID 20160973.

- ^ Berns G, Brooks A, Spivak M (2012). Neuhauss SC (ed.). "Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e38027. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738027B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038027. PMC 3350478. PMID 22606363.

- ^ Tomasello M, Kaminski J (4 September 2009). "Like Infant, Like Dog". Science. 325 (5945): 1213–1214. doi:10.1126/science.1179670. PMID 19729645. S2CID 206522649.

- ^ Serpell JA, Duffy DL (2014). "Dog Breeds and Their Behavior". Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior. pp. 31–57. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-53994-7_2. ISBN 978-3-642-53993-0.

- ^ a b c d Cagan A, Blass T (December 2016). "Identification of genomic variants putatively targeted by selection during dog domestication". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16 (1): 10. Bibcode:2016BMCEE..16...10C. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0579-7. PMC 4710014. PMID 26754411.

- ^ Cagan A, Blass T (2016). "Identification of genomic variants putatively targeted by selection during dog domestication". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16 (1): 10. Bibcode:2016BMCEE..16...10C. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0579-7. PMC 4710014. PMID 26754411.

- ^ Almada RC, Coimbra NC (June 2015). "Recruitment of striatonigral disinhibitory and nigrotectal inhibitory GABAergic pathways during the organization of defensive behavior by mice in a dangerous environment with the venomous snake Bothrops alternatus (Reptilia, Viperidae)". Synapse. 69 (6): 299–313. doi:10.1002/syn.21814. PMID 25727065.

- ^ Lord K, Schneider RA, Coppinger R (2016). "Evolution of Working Dogs". In Serpell J (ed.). The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–66. doi:10.1017/9781139161800. ISBN 978-1-107-02414-4.

- ^ vonHoldt BM, Shuldiner E, Koch IJ, Kartzinel RY, Hogan A, Brubaker L, et al. (7 July 2017). "Structural variants in genes associated with human Williams-Beuren syndrome underlie stereotypical hypersociability in domestic dogs". Science Advances. 3 (7): e1700398. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0398V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700398. PMC 5517105. PMID 28776031.

- ^ González-Martínez Á, Muñiz de Miguel S, Graña N, Costas X, Diéguez FJ (13 March 2023). "Serotonin and Dopamine Blood Levels in ADHD-Like Dogs". Animals. 13 (6): 1037. doi:10.3390/ani13061037. PMC 10044280. PMID 36978578.

- ^ Sulkama S, Puurunen J, Salonen M, Mikkola S, Hakanen E, Araujo C, et al. (October 2021). "Canine hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention share similar demographic risk factors and behavioural comorbidities with human ADHD". Translational Psychiatry. 11 (1): 501. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01626-x. PMC 8486809. PMID 34599148.

- ^ "How to Handle Aggression Between Dogs (Inter-Dog Aggressive Behavior)". petmd.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Fan Z, Bian Z, Huang H, Liu T, Ren R, Chen X, et al. (21 February 2023). "Dietary Strategies for Relieving Stress in Pet Dogs and Cats". Antioxidants. 12 (3): 545. doi:10.3390/antiox12030545. PMC 10045725. PMID 36978793.

- ^ "Dogs and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)". American Kennel Club. American Kennel Club's Staff. 22 May 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ NutriSource (19 October 2022). "What Natural Instincts Do Dogs Have?". NutriSource Pet Foods. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Vetter SG, Rangheard L, Schaidl L, Kotrschal K, Range F (13 September 2023). "Observational spatial memory in wolves and dogs". PLOS ONE. 18 (9): e0290547. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1890547V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0290547. PMC 10499247. PMID 37703235.

- ^ Hart BL, Hart LA, Thigpen AP, Tran A, Bain MJ (May 2018). "The paradox of canine conspecific coprophagy". Veterinary Medicine and Science. 4 (2): 106–114. doi:10.1002/vms3.92. PMC 5980124. PMID 29851313.

- ^ Nganvongpanit K, Yano T (September 2012). "Side Effects in 412 Dogs from Swimming in a Chlorinated Swimming Pool". The Thai Journal of Veterinary Medicine. 42 (3): 281–286. doi:10.56808/2985-1130.2398.

- ^ Nganvongpanit K, Tanvisut S, Yano T, Kongtawelert P (9 January 2014). "Effect of Swimming on Clinical Functional Parameters and Serum Biomarkers in Healthy and Osteoarthritic Dogs". ISRN Veterinary Science. 2014: 459809. doi:10.1155/2014/459809. PMC 4060742. PMID 24977044.

- ^ Rossi L, Valdez Lumbreras AE, Vagni S, Dell'Anno M, Bontempo V (15 November 2021). "Nutritional and Functional Properties of Colostrum in Puppies and Kittens". Animals. 11 (11): 3260. doi:10.3390/ani11113260. PMC 8614261. PMID 34827992.