Killer application

A killer application (often shortened to killer app) is any software that is so necessary or desirable that it proves the core value of some larger technology, such as its host computer hardware, video game console, software platform, or operating system.[1] Consumers would buy the host platform just to access that application, possibly substantially increasing sales of its host platform.[2][3]

Examples

[edit]

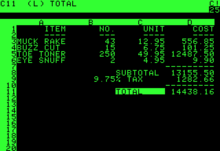

Although the term was coined in the late 1980s[4][5] one of the first retroactively recognized examples of a killer application is the VisiCalc spreadsheet, released in 1979 for the Apple II.[6][7] Because it was not released for other computers for 12 months, people spent US$100 (equivalent to $400 in 2023) for the software first, then $2,000 to $10,000 (equivalent to $8,000 to $42,000) on the requisite Apple II.[8] BYTE wrote in 1980, "VisiCalc is the first program available on a microcomputer that has been responsible for sales of entire systems",[9] and Creative Computing's VisiCalc review is subtitled "reason enough for owning a computer".[10] Others also chose to develop software, such as EasyWriter, for the Apple II first because of its higher sales, helping Apple defeat rivals Commodore International and Tandy Corporation.[8]

The co-creator of WordStar, Seymour Rubinstein, argued that the honor of the first killer app should go to that popular word processor, given that it came out a year before VisiCalc and that it gave a reason for people to buy a computer.[11] However, whereas WordStar could be considered an incremental improvement (albeit a large one) over smart typewriters like the IBM Electronic Selectric Composer,[12] VisiCalc, with its ability to instantly recalculate rows and columns, introduced an entirely new paradigm and capability.[13]

Although released four years after VisiCalc, Lotus 1-2-3 also benefited sales of the IBM PC.[6] Noting that computer purchasers did not want PC compatibility as much as compatibility with certain PC software, InfoWorld suggested "let's tell it like it is. Let's not say 'PC compatible', or even 'MS-DOS compatible'. Instead, let's say '1-2-3 compatible'."[8][14]

The UNIX Operating System became a killer application[citation needed] for the DEC PDP-11 and VAX-11 minicomputers during roughly 1975–1985. Many of the PDP-11 and VAX-11 processors never ran DEC's operating systems (RSTS or VAX/VMS), but instead, they ran UNIX, which was first licensed in 1975. To get a virtual-memory UNIX (BSD 3.0), requires a VAX-11 computer. Many universities wanted a general-purpose timesharing system that would meet the needs of students and researchers. Early versions of UNIX included free compilers for C, Fortran, and Pascal, at a time when offering even one free compiler was unprecedented. From its inception, UNIX drives high-quality typesetting equipment and later PostScript printers using the nroff/troff typesetting language, and this was also unprecedented. UNIX is the first operating system offered in source-license form (a university license cost only $10,000, less than a PDP-11), allowing it to run on an unlimited number of machines, and allowing the machines to interface to any type of hardware because the UNIX I/O system is extensible.[original research?]

Usage

[edit]One mark of a good computer is the appearance of a piece of software specifically written for that machine that does something that, for a while at least, can only be done on that machine.

— Steven Levy, 1985[6]

The earliest recorded use of the term in print is in the May 24, 1988 issue of PC Week: "Everybody has only one killer application. The secretary has a word processor. The manager has a spreadsheet."[15][16]

The definition of "killer app" came up during the deposition of Bill Gates in the United States v. Microsoft Corp. antitrust case. He had written an email in which he described Internet Explorer as a killer app. In the questioning, he said that the term meant "a popular application," and did not connote an application that would fuel sales of a larger product or one that would supplant its competition, as the Microsoft Computer Dictionary defined it.[17]

Introducing the iPhone in 2007, Steve Jobs said that "the killer app is making calls".[18] Reviewing the iPhone's first decade, David Pierce for Wired wrote that although Jobs prioritized a good experience making calls in the phone's development, other features of the phone soon became more important, such as its data connectivity and ability to install third-party software (which was added later).[19]

The World Wide Web (through the web browsers Mosaic and Netscape Navigator) is the killer app that popularized the Internet,[20] as is the music sharing program Napster.[21]

Applications and operating systems

[edit]- 1979: Apple II: VisiCalc (first spreadsheet program and killer app)[22]

- 1979: TRS-80, CP/M systems: WordStar[11] 1982: ported to CP/M-86 and IBM PC compatible/MS-DOS

- 1983: IBM PC compatible/MS-DOS: Lotus 1-2-3 (spreadsheet)[22]

- 1985: Macintosh: Aldus (now Adobe) PageMaker (first desktop publishing program)[23]

- 1985: AmigaOS: Deluxe Paint, Video Toaster, Prevue Guide

- 1993: Acorn Archimedes: Sibelius[24]

Video games

[edit]The term applies to video games that persuade consumers to buy a particular video game console or accessory, by virtue of platform exclusivity. Such a game is also called a "system seller".

- Space Invaders, originally released for arcades in 1978, became a killer app when it was ported to the Atari VCS console in 1980, quadrupling sales of the three-year-old console.[25]

- Star Raiders, released in 1980, may have been a system-seller for the Atari 400 and 800 computers.[26] Another was Eastern Front (1941), released in 1981.[27]

- Defender of the Crown, released in 1986 for the Amiga as the first game from Cinemaware, has graphics which "have set new standards for computer game".[citation needed]

- In 1996, Computer Gaming World wrote that Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (1981) "sent AD&D fans scrambling to buy Apple IIs".[28]

- The Famicom home port of Xevious is considered the console's first killer app, which caused system sales to jump by nearly 2 million units.[29][30]

- Computer Gaming World stated that The Legend of Zelda on the Nintendo Entertainment System, Phantasy Star II on the Sega Genesis, and Far East of Eden for the NEC TurboGrafx-16 were killer apps for their consoles.[31]

- The Super Mario, Final Fantasy, and Dragon Quest series were killer apps for Nintendo's Famicom and Super Famicom consoles in Japan.[32]

- John Madden Football's popularity in 1990 helped the Genesis gain market share against the Super NES in North America.[33][34]

- Sonic the Hedgehog, released in 1991, was hailed as a killer app as it revived sales of the three-year-old Genesis.[35]

- Mortal Kombat helped pushed the sales of the Genesis due to being uncensored unlike the Nintendo version.[36]

- Streets of Rage became a system seller for the Mega Drive/Genesis in the UK.[37]

- Street Fighter II, originally released for arcades in 1991, became a system-seller for the Super NES when it was ported to the platform in 1992.[38]

- Donkey Kong Country for the SNES helped Nintendo's comeback against Sega.[39]

- Myst and The 7th Guest, both released in 1993, drove adoption of CD-ROM drives for personal computers.[40]

- Virtua Fighter 2, Nights into Dreams, and Sakura Wars are the killer apps for the Sega Saturn.[41][42][43]

- Euro 96 and Sega Rally Championship are major system-sellers for the Sega Saturn in the United Kingdom, with the latter becoming the fastest selling CD game.[44][45]

- Die Hard Arcade and Fighters Megamix boosted the Sega Saturn's sales in the United States.[46]

- Ridge Racer,[47][48] Tekken,[49] Wipeout,[50][51] Tomb Raider,[52] and Crash Bandicoot[53][54] are the killer apps for the PlayStation. Tomb Raider was released for the Sega Saturn first and for MS-DOS at the same time, but the games contributed substantially to the original PlayStation's early success. See Blache Fabian & Lauren Fielder and NG Alphas.[citation needed]

- Final Fantasy VII is another killer app for the PlayStation. Computing Japan magazine said that it was largely responsible for the PlayStation's global installed base increasing 60% from 10 million units sold by November 1996 to 16 million units sold by May 1997.[32][55]

- Super Mario 64 and GoldenEye 007 are the killer apps for the Nintendo 64.[56][57]

- Virtua Fighter 3, Sonic Adventure, and The House of the Dead 2 are the killer apps for the Dreamcast.[58][59][60]

- Gran Turismo 3 and the Grand Theft Auto games are the killer apps for the PlayStation 2.[62][49]

- Star Wars Rogue Squadron II: Rogue Leader, Super Smash Bros. Melee, and Super Mario Sunshine are the killer apps for the GameCube.[63][64][65]

- Halo: Combat Evolved and Halo 2 are the killer apps for the Xbox,[66] and the subsequent series entries became killer apps for the Xbox 360 and Xbox One.[67]

- Many video game and technology critics call Xbox Live a more general killer app for the Xbox.[68]

- Blue Dragon is a killer app for the Xbox 360 in Japan.[69]

- Wii Sports is the killer app for the Wii.[70]

- Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots boosted PlayStation 3 sales.[71][72]

- Mario Kart 8 is a killer app for the Wii U in the UK.[73]

- The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is a killer app for the Nintendo Switch.[74][75][76]

- Half-Life: Alyx is a killer app for virtual reality headsets,[77][78][79] as the first true AAA virtual reality game.[80][81] Sales of VR headsets such as the Valve Index increased dramatically after its announcement, suggesting users bought the product specifically for the game.[82]

- Microsoft Flight Simulator was called a killer app for Xbox Game Studios's Xbox Game Pass subscription, and the Xbox Series X/S.[83]

- Pokémon games are killer apps for Nintendo handhelds,[84] often topping the best-selling charts for whatever system they appear on.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Killer app". Merrian-Webmaster. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Scannell, Ed (February 20, 1989). "OS/2: Waiting for the Killer Applications". InfoWorld. Vol. 11, no. 8. Menlo Park, CA: InfoWorld Publications. pp. 41–45. ISSN 0199-6649.

- ^ Kask, Alex (September 18, 1989). "Revolutionary Products Are Not in the Industry's Near Future". InfoWorld. Vol. 11, no. 38. Menlo Park, CA: InfoWorld Publications. p. 68. ISSN 0199-6649.

- ^ Dvorak, John (July 1, 1989). "Looking to OS/2 for the next killer app is barking up the wrong tree. Here's where they really come from". PC Magazine. Ziff Davis. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ "killer app". dictionary.com. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

Origin of killer app 1985-1990

- ^ a b c Levy, Steven (January 1985). "The Life and Times of PC junior". Popular Computing. p. 92. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ D.J. Power, A Brief History of Spreadsheets, DSSResources.COM, v3.6, August 30, 2004

- ^ a b c McMullen, Barbara E. and John F. (February 21, 1984). "Apple Charts The Course For IBM". PC Magazine. p. 126. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Ramsdell, Robert E (November 1980). "The Power of VisiCalc". BYTE. pp. 190–192. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Green, Doug (August 1980). "VisiCalc: Reason Enough For Owning A Computer". Creative Computing. p. 26. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Bergin, Thomas J. (October–December 2006). "The Origins of Word Processing Software for Personal Computers: 1976-1985". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 28 (4): 32–47. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2006.76. S2CID 18895790.

- ^ Baron, Dennis (2012). A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780199914005.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin (October 2, 2003). The History of Mathematical Tables: From Sumer to Spreadsheets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 328. ISBN 9780191545214.

- ^ Clapp, Doug (February 27, 1984). "PC compatibility". InfoWorld. p. 22. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ "PC Week". PC Week. Vol. 39, no. 1. May 24, 1988.

- ^ "killer, n." Oxford University Press – via Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YeLBQCpCi9c&t=592 [bare URL]

- ^ Newton, Cal (January 25, 2019). "Steve Jobs Never Wanted Us to Use Our iPhones Like This". New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Pierce, David. "Even Steve Jobs Didn't Predict the iPhone Decade". Wired. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Markoff, John (December 8, 1993). "BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY; A Free and Simple Computer Link". New York Times.

- ^ Brad King (May 15, 2002). "The Day the Napster Died". Wired.

- ^ a b Vaughan-Nichols, Steven (May 14, 2013). "Goodbye, Lotus 1-2-3". Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Robinson, Phillip (March 2, 1992). "Next's Giant Step". Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^

Bourgeois, Derek (November 1, 2001). "Score yourself an orchestra". The Guardian. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

Many composers bought an Archimedes simply to have access to the program.

- ^ "The Definitive Space Invaders". Retro Gamer. No. 41. Imagine Publishing. September 2007. pp. 24–33. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Williams, Gregg (May 1981). "Star Raiders". BYTE. p. 106. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Greenlaw, Stanley (November–December 1981). "Eastern Front". Computer Gaming World (review). pp. 29–30. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ 遠藤昭宏 (June 2003). "ユーゲーが贈るファミコン名作ソフト100選 アクション部門". ユーゲー. No. 7. キルタイムコミュニケーション. pp. 6–12.

- ^ Kurokawa, Fumio (March 17, 2018). "ビデオゲームの語り部たち 第4部:石村繁一氏が語るナムコの歴史と創業者・中村雅哉氏の魅力". 4Gamer.net. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Adams, Roe R. III (November 1990). "Westward Ho! (Toward Japan, That Is)". Computer Gaming World. p. 83. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ a b "The lack of a killer app". Computing Japan. Vol. 36–41. LINC Japan. 1997. p. 44.

Noguchi points out that every time sales of a particular game console have taken off, it has been because it had a new "killer software". Nintendo had Super Mario Bros., Dragon Quest, and Final Fantasy. And Sony PlayStation now has Final Fantasy VII, which has been selling like hotcakes since it was released at the end of January. Total shipments of PlayStation, which numbered 10 million worldwide as of November 1996, had jumped to 12 million by February 14 and 16 million by the end of May.

- ^ Hruby, Patrick (August 5, 2010). "The Franchise". ESPN. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Fahs, Travis (August 6, 2008). "IGN Presents the History of Madden". IGN. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ Gates, James (May 4, 2018). "The Creation of Sonic The Hedgehog". Culture Trip. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Icons - Mortal Kombat - Part 2" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Sonic, Street Fighter and the 'golden age' of gaming magazines". BBC News. September 4, 2019.

- ^ Patterson, Eric L. (November 3, 2011). "EGM Feature: The 5 Most Influential Japanese Games Day Four: Street Fighter II". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ "Sega v Nintendo: Sonic, Mario and the 1990's console war". BBC News. May 12, 2014.

- ^ "PC Retroview: Myst". IGN. August 1, 2000. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ Hickman, Sam (December 15, 1995). "Virtua Sell Out!". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 3 (January 1996). Emap International Limited. p. 7.

- ^ "SEGA Central". Archived from the original on December 20, 1996.

- ^ IGN Staff (October 19, 1999). "Sakura Wars Strikes the Dreamcast". IGN.

- ^ "Tonight We're Going to Party like it's 1996!". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 16. Emap International Limited. February 1997. p. 10.

- ^ "Sega go to the Top of the Charts!". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 5. Emap International Limited. March 1996. p. 6.

- ^ "Sega Online: Buzz (Press Releases)". www.sega.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 1997. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Levy, Stuart; Semrad, Ed (January 1997). "Rage Racer". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 90. Ziff Davis. p. 112.

- ^ "Top 25 Games of All Time: Complete List". IGN. 23 January 2002. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ a b Stevens, Chris (January 4, 2011). Designing for the iPad: Building Applications that Sell. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-97693-7.

- ^ Hickman, Sam (March 1996). "The Thrill of the Chase!". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 5. Emap International Limited. p. 36.

And if there was one game that sold Playstation on launch, it was WipEout

- ^ Leadbetter, Richard (December 4, 2014). "20 years of PlayStation: the making of WipEout". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Blache, Fabian; Fielder, Lauren (October 31, 2000). "GameSpot's History of Tomb Raider". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Kotzer, Zack (December 3, 2016). "Crash Bandicoot's Jeans Look Super Realistic in Remastered Trilogy". Vice. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

Taking the classic 2D platformer 3D in a more literal fashion, jumping around obstacles along zany corridors, the [Crash Bandicoot series] quickly became PlayStation's killer app.'

- ^ Jaime Banks; Robert Mejia; Aubrie Adams (2017). 100 Greatest Video Game Characters. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 45. ISBN 9781442278134.

...Moreover, Crash was one of the first 3D characters to feature higly expressive facial animations, helping the game to serve as a "killer app" for PlayStation.

- ^ Goh, Clement (November 16, 2020). "The Road to PlayStation 5: A CGM Story". CGMagazine Online. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

...Called Final Fantasy VII, its combination of real-time 3D graphics and rich movie-quality storytelling gave Sony a permanent formula. [...] The PlayStation also found its killer app, selling 10 million copies worldwide and put more systems in households.

- ^ Hutchinson, Lee (January 13, 2013). "How I launched 3 consoles (and found true love) at Babbage's store no. 9". Ars Technica. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "The 52 Most Important Video Games of All Time (page 5 of 8)". GamePro. April 24, 2007. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "A Brief History of Dreamcast". March 2, 1999.

- ^ "Sega Dreamcast at 20: The futuristic games console that came too soon". TheGuardian.com. November 28, 2018.

- ^ "SEGA Needs Back on iPhone". May 15, 2009.

- ^ "Sega Rolls On". Next Generation. December 1999. p. 10.

- ^ Nicholson, Zy (September 2001). "Final Reality". Official UK PlayStation 2 Magazine. No. 11. pp. 49, 50.

- ^ "The Best Star Wars Games Ever Made". May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Super Smash Bros. "Million" in Japan". January 17, 2002.

- ^ "MARIO DELIVERS! Super Mario Sunshine Launches At Record Pace, Boosts Hardware Sales". Business Wire. September 5, 2002. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Craig Glenday, ed (March 11, 2008). "Hardware History II". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- ^ Sun, Leo (December 15, 2016). "Why 'Halo: The Master Chief Collection' Will Save the Xbox One -- The Motley Fool". The Motley Fool. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (February 24, 2014). Vintage Game Consoles. CRC Press. ISBN 9781135006501. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Video Game News & Reviews". Archived from the original on December 23, 2007.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "2007's Ten Burning Questions, Answered". Wired.

- ^ Tanaka, John (June 17, 2008). "Nearly 500,000 for Metal Gear Solid 4 in Japan". IGN.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2021). The Ultimate History of Video Games, Volume 2: Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft, and the Billion-Dollar Battle to Shape Modern Gaming (2nd ed.). Crown Publishing Group. p. 408-410. ISBN 9781984825445.

- ^ "Mario Kart 8 boosts UK Wii U hardware sales 666% - CVG US". Archived from the original on June 2, 2014.

- ^ Craddock, Ryan (March 3, 2021). "Anniversary: Nintendo Switch Launched Four Years Ago Today". Nintendo Life. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Lawver, Bryan (2021). "All 17 Legend of Zelda games, ranked from worst to best". Inverse.com. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Camden (August 20, 2020). "Why Breath Of The Wild Fans Will LOVE A Short Hike". Screen Rant. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ McKeand, Kirk (March 23, 2020). "Half-Life: Alyx review - VR's killer app is a key component in the Half-Life story". VG247. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Carbotte, Kevin (March 23, 2020). "Half-Life: Alyx Gameplay Review: (Almost) Every VR Headset Tested". Tom's Hardware. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Andrew (March 23, 2020). "Review: Half-Life Alyx is VR's stunning killer app". VGC. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Oloman, Jordan (March 23, 2020). "Half-Life: Alyx is a watershed moment for virtual reality | TechRadar". www.techradar.com.

- ^ "CES 2020: Teslasuit Will Unveil New Haptic VR Gloves". Tech Times. December 27, 2019.

- ^ Parlock, Joe (December 9, 2019). "The Valve Index VR Headset Sells Out Before Christmas Thanks To 'Half-Life: Alyx'", Forbes. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Microsoft Flight Simulator review: The killer app". August 17, 2020.

- ^ Bell, David (2004). Cyberculture: The Key Concepts. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 9780415247542.