Perkin Warbeck

| Perkin Warbeck | |

|---|---|

| Pretender | |

16th-century copy by Jacques Le Boucq of the only known contemporary portrait of Warbeck, Library of Arras[1][2] | |

| Born | Pierrechon de Werbecque c. 1474 Tournai, Tournaisis |

| Died | 23 November 1499 (aged 24–25) Tyburn, Middlesex, England |

| Title(s) | Pretended Duke of York |

| Throne(s) claimed | England |

| Pretend from | 1490 |

| Connection with | Claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, son of Edward IV of England |

| Royal House | In the name of the House of York |

| Father | Jehan de Werbecque; claimed to be Edward IV of England |

| Mother | Katherine de Faro; claimed to be Elizabeth Woodville |

| Spouse | Lady Catherine Gordon |

Perkin Warbeck (c. 1474 – 23 November 1499) was a pretender to the English throne claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, who was the second son of Edward IV and one of the so-called "Princes in the Tower". Richard, were he alive, would have been the rightful claimant to the throne, assuming that his elder brother Edward V was dead and that he was legitimate—a point that had been previously contested by his uncle, King Richard III.

Due to the uncertainty as to whether Richard had died (either of some natural cause or having been murdered in the Tower of London) or whether he had somehow survived, Warbeck's claim gained some support. Followers may have truly believed Warbeck was Richard or may have supported him simply because of their desire to overthrow the reigning king, Henry VII, and reclaim the throne. Given the lack of knowledge regarding Richard's fate, and having received support outside England, Warbeck emerged as a significant threat to the newly established Tudor dynasty; Henry declared Warbeck an impostor.

Warbeck made several landings in England backed by small armies but met strong resistance from the King's men and surrendered in Hampshire in 1497. After his capture, he retracted his claim, writing a confession in which he said he was a Fleming born in Tournai around 1474. He was executed on 23 November 1499. Dealing with Warbeck cost Henry VII over £13,000 (equivalent to £12,916,000 in 2023), putting a strain on Henry's weak state finances.

Early life

[edit]Perkin Warbeck's personal history is fraught with many unreliable and varying statements.[3] Warbeck said that he was Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger son of King Edward IV, who had disappeared mysteriously along with his brother Edward V after Richard, Duke of Gloucester, usurped the throne as King Richard III following the elder Edward's death in 1483. After Warbeck was captured and interrogated in 1497 under the eye of King Henry VII, another version of his life was published, based on his confession. This confession is considered by many historians to be possibly only partially true as it was procured under duress.[citation needed]

According to the confession, Warbeck was born to a woman called Katherine de Faro, wife of John Osbeck (also known as Jehan de Werbecque).[4] Osbeck was Flemish and held the occupation of comptroller to the city of Tournai, in present-day Belgium.[5] These family ties are backed up by several municipal archives of Tournai which mention most of the people whom Warbeck declared he was related to.[6] Around the age of ten, he was taken to Antwerp by his mother to learn Dutch.[citation needed] From there, he was undertaken by several masters around Antwerp and Middelburg before being employed by a local English merchant named John Strewe for a few months [6] where he traded cloth.[7]

After his time in the Netherlands, Warbeck yearned to visit other countries and was hired by a Breton merchant.[5] This merchant eventually brought Warbeck to Cork, Ireland, in 1491 when he was about 17, and there he learned to speak English.[5] Warbeck then claims that upon seeing him dressed in silk clothes, some of the citizens of Cork who were Yorkists demanded to do "him the honour as a member of the Royal House of York."[6] He said they did this because they were resolved on gaining revenge on the King of England; they decided that he would claim to be the younger son of the late King Edward IV.[6]

Claim to the English throne

[edit]Warbeck first claimed the English throne at the court of Burgundy in 1490, where jeton coins were minted for him. Warbeck explained his (i.e. Richard of Shrewsbury's) mysterious disappearance by claiming that his brother Edward V had been murdered, but he had been spared by his brother's (unidentified) murderers because of his age and "innocence". However, he had been made to swear an oath not to reveal his true identity for "a certain number of years".[8] He claimed that from 1483 to 1490, he had lived on the continent of Europe under the protection of Yorkist loyalists, but when his main guardian, Sir Edward Brampton, returned to England, he was left free. He then declared his true identity.[8]

In 1491, Warbeck landed in Ireland in the hope of gaining support for his claim as Lambert Simnel had four years previously. His cause was promoted by John Atwater, a former Mayor of Cork and ardent Yorkist, who may have been instrumental in helping him assume the identity of Richard. However, little support materialized for an active rebellion, and Warbeck was forced to return to mainland Europe. There his fortunes improved. He was first received by Charles VIII of France, but in 1492 he was expelled under the terms of the Treaty of Etaples, by which Charles had agreed not to shelter rebels against Henry VII. After an English expedition laid siege to Boulogne, Charles VIII agreed to withdraw all backing from Warbeck. In the Duchy of Burgundy, however, Warbeck was publicly recognized as Richard of Shrewsbury by Margaret of York, widow of Charles the Bold, sister of Edward IV, and thus the aunt of the Princes in the Tower. Whether Margaret—who left England to marry before either of her nephews were born—truly believed that the pretender was her nephew Richard, or whether she considered him a fraud but supported him anyway, is unknown, but she tutored him in the ways of the Yorkist court.

Henry complained to Philip of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, about the harbouring of the pretender. When Henry was ignored, he imposed a trade embargo on Burgundy, cutting off important Burgundian trade connections with England. The pretender was also welcomed by various other monarchs and was known in international diplomacy as the Duke of York. At the invitation of Duke Philip's father, Emperor Maximilian I, in 1493, Perkin attended the funeral of Maximilian's father Frederick III and was recognised as King Richard IV of England.[9]

Support in England (Perkin Warbeck conspiracy)

[edit]Pro-Yorkist sympathy in England involved important figures making it known that they were prepared to back Warbeck's claims. These included Lord Fitzwater, Sir Simon Montfort, Sir Thomas Thwaites (ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer), Sir William Stanley (the Lord Chamberlain) and Sir Robert Clifford. Clifford went over to mainland Europe and wrote back to his friends to confirm Warbeck's real identity as Prince Richard.[10]

King Henry ordered the group of supporters to be rounded up and put on trial. All were duly arrested, together with William D'Aubeney, Thomas Cressener, Thomas Astwode, Robert Ratcliff and others. Lord Fitzwater was sent as a prisoner to Calais and later beheaded for trying to bribe his gaolers.

In show trials in January 1495, all the conspirators were initially condemned to death, although six, including Thwaites, were then pardoned and their sentences commuted to imprisonment and fines. Within days Sir Simon Montfort, Robert Ratcliff and William D'Aubeney were beheaded at Tower Hill and Cressener and Astwode pardoned at the block. Later the same month Sir William Stanley was also beheaded. Other members of the group were imprisoned and fined.[11] Sir Robert Clifford was pardoned and rewarded for revealing the names of the conspirators.

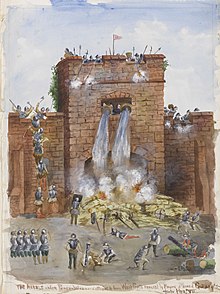

First landing in England

[edit]On 3 July 1495, funded by Margaret of Burgundy, Warbeck landed at Deal in Kent, hoping for a show of popular support. They were confronted by locals loyal to Henry VII in the ensuing Battle of Deal. Warbeck's small army was routed and 150 of the pretender's troops were killed without Warbeck even disembarking. He was forced to retreat almost immediately, this time to Ireland. There he found support from Maurice FitzGerald, 9th Earl of Desmond, and laid siege to Waterford, but, meeting resistance, he fled to Scotland.

Support in Scotland (1495–1496)

[edit]

Warbeck was well received by James IV of Scotland. Warbeck followed the court and was a Christmas guest at Linlithgow Palace in 1495.[12] James realised that Warbeck's presence gave him international leverage. As Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain were negotiating an alliance with Henry VII, James IV knew that Spain would help him in his struggles with England in order to prevent the situation escalating into war with France.[13]

Spanish ambassadors arrived in Edinburgh, and later Pedro de Ayala was established as a resident ambassador during the crisis. Warbeck married Lady Catherine Gordon, a daughter of George Gordon, 2nd Earl of Huntly. The marriage was celebrated in Edinburgh with a tournament.[14] James gave Warbeck clothes for the wedding and armour covered with purple silk.[15]

Historian Katie Stevenson suggests the clothing bought for the tournament shows Warbeck fought in a team with the king and four knights.[16] A copy of a love letter in Latin obtained by Pedro de Ayala is thought to be Warbeck's proposal to Lady Catherine.[17] However, James's biographer Norman Macdougall comments that it is clear that nobody, with the possible exception of Margaret of Burgundy, took seriously his claim to be the prince; his marriage to a junior Scots noblewoman was scarcely what might be expected for a potential king of England.[13]

In September 1496, James IV prepared to invade England with Warbeck. A red, gold and silver banner was made for Warbeck as the Duke of York; James's armour was gilded and painted, and the royal artillery was prepared.[18] John Ramsay of Balmain (who called himself Lord Bothwell) described the events for Henry VII. He saw Roderic de Lalaing, a Flemish knight, arrive with two little ships and 60 German soldiers and meet James IV and talk to Warbeck.[19] Guns provided for the raid from Edinburgh Castle included two great French "curtalds", 10 falconets or little serpentines, and 30 iron breech-loading "cart guns" with 16 close-carts or wagons for the munitions.[20] Bothwell estimated the invasion force would last only four to five days in England before it ran out of provisions. He suggested, from the safety of Berwick-upon-Tweed, that the Scots could be vanquished by a modest English force attacking from north and south in a pincer movement.[21]

The Scottish host assembled near Edinburgh; James IV and Warbeck offered prayers at Holyrood Abbey on 14 September and on the next day at St Triduana's Chapel and Our Lady Kirk of Restalrig.[22] On 19 September 1496 the Scottish army was at Ellem and on 21 September they crossed the Tweed at Coldstream. Miners set to work to demolish Heaton Castle on 24 September, but the army quickly retreated when resources were expended[23] and hoped-for support for Perkin Warbeck in Northumberland failed to materialise. According to an English record, the Scots penetrated four miles into England with a royal banner displayed and destroyed three or four little towers (or Bastle houses). They left on 25 September 1496 when an English army commanded by Lord Neville approached from Newcastle.[24] When news of this invasion reached Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, on 21 October 1496, he wrote to his ambassador in Spain to request the Spanish monarchs make peace between England and Scotland. The peace mission was entrusted to the Spanish ambassador in Scotland, Pedro de Ayala, who had been Perkin's companion in Northumberland.[25]

Later, wishing to be rid of Warbeck, James IV provided a ship called the Cuckoo and a hired crew under a Breton captain, Guy Foulcart.[26] Horses were hired for 30 of Warbeck's companions to ride to the ship at Ayr on 5 July 1497. Pedro de Ayala accompanied Perkin to Ayr. Perkin pawned a horse for cash in Ayr and sailed to Waterford in shame.[27] James IV made peace with England by signing the Treaty of Ayton at St Dionysius's Church in Ayton in Berwickshire. Once again Perkin attempted to lay siege to Waterford, but this time his effort lasted only eleven days before he was forced to flee Ireland, chased by four English ships. According to some sources, by this time he was left with only 120 men on two ships.[citation needed] Bacon's History of the Reign of King Henry VII said he had "in his company four small barks, with some sixscore or sevenscore fighting men".[28]

Landing in Cornwall

[edit]

On 7 September 1497, Warbeck landed at Whitesand Bay, two miles north of Land's End, in Cornwall, hoping to capitalise on the Cornish people's resentment in the aftermath of their uprising only three months earlier.[29] Warbeck proclaimed that he could put a stop to extortionate taxes levied to help fight a war against Scotland and was warmly welcomed. He was declared "Richard IV" on Bodmin Moor and his Cornish army some 6,000 strong entered Exeter before advancing on Taunton.[30][31] Henry VII sent his chief general, Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney, to attack the Cornish and when Warbeck heard that the King's scouts were at Glastonbury he panicked and deserted his army.

Warbeck was captured at Beaulieu Abbey in Hampshire where he surrendered. Henry VII reached Taunton on 4 October 1497, where he received the surrender of the remaining Cornish army. The ringleaders were executed and others fined. Warbeck was imprisoned, first at Taunton, then at the Tower of London, where he was "paraded through the streets on horseback amid much hooting and derision of the citizens".[32]

Imprisonment and death

[edit]Warbeck was initially treated well by Henry. As soon as he confessed to being an impostor, he was released from the Tower of London and was given accommodation at Henry's court. He was even allowed to be present at royal banquets. He was, however, kept under guard and was not allowed to sleep with his wife, who was living under the protection of the queen.

After eight months at court, Warbeck tried to escape. He was quickly recaptured. He was then held in the Tower, initially in solitary confinement, and later alongside the 17th Earl of Warwick; the two tried to escape in 1499. Captured once again, Warbeck was led from the Tower to Tyburn, London on 23 November 1499, where he read out a confession and was hanged.[8][33] Warbeck's Irish ally John Atwater was also executed at Tyburn on the same day. The Earl of Warwick was beheaded on Tower Hill on 28 November 1499.

Warbeck was buried in Austin Friars, London.[34] The presumed site of his unmarked grave is at the Dutch Church, Austin Friars.

His story was featured in Francis Bacon's 1622 work History of the Reign of King Henry VII.

Appearance

[edit]Perkin reportedly resembled Edward IV in appearance, which has led to speculation that he might have been Edward's illegitimate son or at least had some genuine connection with the York family. Francis Bacon believed he was one of Edward's many illegitimate children.[8] It has also been suggested that he was a son of one of Edward's siblings, either Richard III or Margaret of York, Warbeck's first major sponsor.[8]

Some authors, for example Horace Walpole, have even gone as far as to claim that Warbeck actually was Richard, Duke of York.[35]

Portrait

[edit]It is often claimed that Perkin's only surviving likeness is a drawing in the Recueil d'Arras by Jacques le Boucq dating from c. 1570. The text labeling the drawing as Perkin Warbeck is in a different hand to inscriptions on other drawings in the collection. It might have been added later. It is then questionable if it indeed depicts Warbeck. Since le Boucq didn't know who the man was, by his time the identity of the man was likely forgotten. However, Le Boucq's original handwriting describes the materials of the man's outfit as "drap dor"(drap d'or=cloth of gold) and "drap darger"(probably drap d'argent=cloth of silver). An outfit fit for royalty, but not pointing to Warbeck specifically.

Within the Recueil d'Arras, the "Perkin Warbeck" drawing is placed among portraits of the Scottish and English royal family (James IV, Margaret Tudor, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York).[36]

This group of drawings in the Recueil d'Arras may be based on the work of Meynnart Wewyck, an artist at the Tudor court who travelled to Scotland in the years after Perkin Warbeck had left.[37] There he was known as "Mynours the English painter".[38] Another painter, Piers, from Antwerp, was his successor at the Scottish court,[39] and he has also been suggested as the source of the Scottish portraits in the Recueil.[40]

Missing Princes Project

[edit]In 2022 Philippa Langley led "The Missing Princes Project" to discover the fate of the Princes in the Tower.[41][42][43] The project began in 2015, following the reburial of Richard III in Leicester and was formally launched in July the following year.[44] In 2023 she claimed to have discovered new evidence that disproved the theory that Richard III was responsible for the deaths of the princes. Along with Rob Rinder, she hosted a Channel 4 programme called Princes in the Tower: The New Evidence, in which she revealed her own theories and new archival discoveries. [45][46] Although praising Langley's discoveries, The Spectator's reviewer called the programme "a calculated insult to the viewer";[47] The Times called it "compelling" and awarded the documentary its "Critics Choice."[48] The programme achieved a large audience [49] with Richard III and the Princes in the Tower trending on Twitter / X. The Richard III Society issued a press release stating:

The disappearance of the princes has always been described as a great unsolved mystery. Why? Because there was no evidence of their fate. Their murder was never more than conjecture, but it was put about by the authorities and – for safety’s sake – only the brave dared to think differently. From now on, history must take account of this new breakthrough evidence. No longer can anyone confidently claim the princes were killed by Richard III.[50]

Three leading members of the Dutch Research Group who had assisted in the project subsequently distanced themselves from Langley's documentary and book, arguing that the documents they had discovered "are in our own opinion open to various interpretations and do not constitute irrefutable proof" for the survival of the princes.[51] Langley responded that her conclusions were based on "the totality of evidence thus assembled and the outcomes of a modern police missing person investigation methodology ... (and not through a traditional historical research method)".[52] Historian Michael Hicks similarly opined that the new documents "do add to knowledge of the Tudor impostors, but they fall short of proof that either Edward V or Richard Duke of York survived beyond their disappearance in the autumn of 1483".[53] Langley again responded that her use of "police investigative methodology" had provided "sufficient reason to conclude" that the two had survived the reign of Richard III.[54]

Warbeck in popular culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

Warbeck's story subsequently attracted writers, most notably the dramatist John Ford, who dramatized the story in his play Perkin Warbeck, first performed in the 1630s.

- Friedrich Schiller wrote a plan and a few scenes for a play about Warbeck; he never finished the play because he gave priority to other works, such as Maria Stuart and Wilhelm Tell.[55][56]

- Mary Shelley, best known as the author of Frankenstein, wrote a romance on the subject of Warbeck, The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck, published in London in 1830.

- Lord Alfred Douglas wrote a poem about Perkin Warbeck in 1893 or 1894. It is included in the Collected Poems of Lord Alfred Douglas, published in 1928.

- In Dorothy L. Sayers's mystery novel Have His Carcase (1932), Lord Peter Wimsey discovers that the murderers lured the victim to his death by playing on his secret belief that he was the hereditary Tsar of Russia, based on his great-great-grandmother's purported morganatic marriage to Nicholas I. When Harriet Vane points out that even if this were true, the man would not be the next in line to the throne, Peter remarks that genealogy has a way of making people believe what they want to believe, saying he knows a "draper's assistant" in Leeds who earnestly believes he will be crowned King of England as soon as he can find the record of his ancestor's marriage to Perkin Warbeck; the fact that Warbeck's claim to the throne was ultimately invalidated, and that the Tudor dynasty he laid claim to has since been replaced by others, doesn't faze him in the least.

- The novel Crown of Roses (1989) by Valerie Anand suggests that Warbeck was the son of an illegitimate son of Richard Duke of York who had been sent to Burgundy as a boy to imply to interested parties that Richard of Shrewsbury had left the Tower alive.

- The historical novel The Tudor Rose (1953) by Margaret Campbell Barnes deals at length with the Warbeck plot and implies that Warbeck actually was Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York.

- Warbeck is the central character in Philip Lindsay's historical novel They Have Their Dreams.

- In 2005 Channel 4 and RDF Media produced a drama entitled Princes in the Tower about the interrogation of Warbeck, starring Mark Umbers. Warbeck almost convinces Henry VII that he really is Richard, Duke of York. Warbeck "remembers" that Henry's mother Margaret Beaufort poisoned his brother Edward V, after which Richard III spirited him away to safety. Warbeck succeeds in alienating King Henry from both his mother and his wife, Elizabeth of York, who now believe Warbeck to be her lost brother. Margaret then shows Warbeck two young men in chains, who she presents as the real princes, locked up for years in isolation and now completely insane. She says Henry knows nothing about them. She forces Warbeck to confess he is an imposter to save the life of his son by Lady Catherine Gordon. Warbeck confesses and is hanged. In the final scene, Margaret is seen overseeing the burial of a piece of regal clothing with two skeletons, while, in voice-over, Thomas More, whose secret account of the events is supposed to be the drama's source, describes how lucky he has been under Henry VIII.

- In the 1972 BBC television series The Shadow of the Tower, Warbeck was portrayed by British actor Richard Warwick.

- The American Shakespeare Center (ASC) in Staunton, Virginia, produced a comedy entitled The Brats of Clarence, written specifically for the ASC 'Blackfriars' stage by Paul Menzer. The play tracks the progress of Perkin Warbeck from the Scottish court to London to claim his birthright as heir to the throne.

- Warbeck and his wife are characters in the novel The Crimson Crown by Edith Layton (1990). The main character is Lucas Lovat, a spy in the Court of Henry VII, and a subplot of the novel is his indecision as to whether Warbeck is, or is not, Prince Richard.

- English comedians Stewart Lee and Richard Herring both make references to Warbeck and fellow pretender Lambert Simnel in much of their work, both as Lee and Herring and individually. Simnel and Warbeck's names have appeared sporadically throughout their material over the years.

- Warbeck's story is retold through the eyes of Grace Plantagenet in The King's Grace by Anne Easter Smith (2009). Grace, an illegitimate daughter of Edward IV, attempts to unravel the mystery surrounding the man who claims to be her half-brother Richard. Rosemary Hawley Jarman, in her novel "We Speak No Treason", also fictionalised unconfirmed speculation that Warbeck could have been another of Edward's illegitimate sons.[57][58]

- In Philippa Gregory's 2009 novel The White Queen, the young Duke of York is sent into hiding by his mother, Elizabeth Woodville, while a changeling is sent to the Tower in his place. In the fifth novel of Gregory's The Cousins' War series, The White Princess, a mysterious pretender appears, claiming to be Richard. King Henry Tudor invents an elaborate false history to justify denial of the pretender's claims, giving him the name Perkin Warbeck (among others). Although the novel never answers the question, Gregory states in the epilogue that she believes Warbeck's claim was genuine.

- A miniseries The White Princess, adapted from Gregory's novel, was first aired on Starz in 2017 where Perkin Warbeck was played by Irish actor Patrick Gibson. Unlike Gregory's original work, the series portrays Warbeck as the genuine Duke of York, who has escaped England and been raised by a Flemish boatmaker.

- A latter section of Terence Morgan's novel The Master of Bruges expands on the theory that Prince Richard escaped to Flanders, grew up in Tournai and returned to England as Perkin Warbeck.

- Four-part audio drama "The Pretender" on History Hit[59]

Further reading

[edit]- Bennett, Michael (21 March 2024). Lambert Simnel and the Battle of Stoke. History Press. ISBN 978-1-80399-723-0.

- Langley, Philippa (November 2023). The Princes in the Tower: Solving History's Greatest Cold Case. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-80399-541-0.[60]

- Amin, Nathen (15 April 2021). Henry VII and the Tudor Pretenders: Simnel, Warbeck, and Warwick. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-7509-1.

- Lewis, Matthew (11 September 2017). The Survival of the Princes in the Tower: Murder, Mystery and Myth. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-8528-4.

- Ashdown-Hill, John (5 January 2015). The Dublin King: The True Story of Edward Earl of Warwick, Lambert Simnel and the 'Princes in the Tower'. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6316-9.

- Arthurson, Ian (4 October 2009). The Perkin Warbeck Conspiracy. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9563-7.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lutkin, Jessica (2016). A/AS Level History for AQA The Wars of the Roses, 1450–1499 Student Book. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9781316504376. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Carson, Annette (2017). Richard III The Maligned King. History Press. p. VII. ISBN 9780752473147.

- ^ Gairdner, James, p. 263

- ^ Gairdner, James, p. 266

- ^ a b c Ure, Peter, ed., p. lxxxviii

- ^ a b c d Gairdner, James, p. 267

- ^ Tillbrook, Michael. The Tudors: England 1485–1603. Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 6 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c d e Weir, Alison, pp. 238–240

- ^ Wroe, Ann, pp. 148–151.

- ^ "Perkin Warbeck". Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Arthurson, Ian. The Perkin Warbeck Conspiracy. [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b William Hepburn, The Household and Court of James IV of Scotland (Boydell, 2023), p. 67.

- ^ a b Macdougall, Norman p. 123–124, 136, 140–141.

- ^ Katie Stevenson, Chivalry and Knighthood in Scotland, 1424-1513 (Boydell, 2006), p. 84.

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 257, 262–264.

- ^ Stevenson, Katie, p. 84

- ^ "Calendar State Papers Spain, vol. 1 (London, 1862), no. 119 & fn".

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 292–296.

- ^ Henry Ellis, Original Letters, Series 1 vol. 1 (London, 1824) p. 30.

- ^ Henry Ellis, Original Letters, Series 1 vol. 1 (London, 1824) p. 31.

- ^ Pinkerton, John, pp. 438–441

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 296, 299–300.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 299–300.

- ^ Bain, Joseph, ed., Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland, 1357–1509, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1888), pp. 418–419 no. 35 (there dated as if '1497'): David Dunlop (1991), 108–109 & fn., quotes another version, and cites four more, noting a mistaken date in Bain (1888).

- ^ Calendar State Papers Milan" (London, 1912), no. 514.

- ^ Robert Kerr Hannay, Letters of James IV (SHS: Edinburgh, 1953), p. 9.

- ^ Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), pp. 342–345.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1885). History of the Reign of King Henry VII. Cambridge University Press. p. 163.

- ^ "Timeline of Cornish History 1066–1700 AD". Cornwall County Council. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "Timeline of Cornish History 1066–1700 AD". www.cornwall.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Payton, Philip (2004). Cornwall: A History. Cornwall Editions Limited. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-904880-05-9.

- ^ "Perkin Warbeck". www.channel4com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2005. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Goble, Rachel (11 November 1999). "The Execution of Perkin Warbeck". History Today (11). Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Great Chronicle of London, Guildhall Library.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1768). "Memoires Litteraires". In Sabor, Peter (ed.). Horace Walpole: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-0415134361.

- ^ Lorne Campbell, 'The Authorship of the Recueil d'Arras', Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 40 (1977), 302.

- ^ Charlotte Bolland & Andrew Chen, 'Meynnart Wewyck and the portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort', Burlington Magazine, 161 (April 2019), 316–318: James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, 1500-1504, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), p. 405.

- ^ Susan Hannabus & Michael Apted, Painters in Scotland (Edinburgh: Scottish Record Society, 1978), 68-69.

- ^ David Ditchburn, Scotland and Europe, the medieval kingdom and its contacts with Christendom, c. 1214–1545, vol. 1 (Tuckwell, 2001), 119.

- ^ Andrea Thomas, Princelie Majestie: The Court of James V (Edinburgh: John Donald), 80: Jill Harrison, 'Fresh Perspectives on Hugo van Goes' Portrait of Margaret of Denmark and the Trinity Altarpiece', Court Historian, 24:2 (2019), 128-9. doi:10.1080/14629712.2019.1626108

- ^ Dunne, Daisy (29 December 2021). "History's greatest whodunnit would be ruined if we solved it, Philippa Langley team findings". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

A team led by Philippa Langley, who found the skeleton of King Richard III under a car park in 2012, have uncovered what they believe to be clues to the survival of Edward V in the Devon village of Coldridge....

- ^ Catling, Chris (22 November 2022). "From the Princes in the Tower to Northumbria's Golden Age". The Past. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Missing Princes Project". Philippa Langley. 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (2023). The Princes in the Tower: Solving History's Greatest Cold Case. Cheltenham: The History Press. p. 26. ISBN 9781803995410.

- ^ Lee Garrett (17 November 2023). "Historian says Richard III did not kill Princes in the Tower in 'landmark' Channel 4 show". Leicester Mercury. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ The Princes in the Tower: The New Evidence Channel 4 Saturday 18 November. Retrieved 20 May 2024. https://www.channel4.com/programmes/the-princes-in-the-tower-the-new-evidence The Princes in the Tower PBS 22 November 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2024. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/preview-the-princes-in-the-tower-ybnnnv/7943/

- ^ James Delingpole (22 November 2023). "A calculated insult to the viewer: Channel 4's The Princes in the Tower – The New Evidence reviewed". The Spectator. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ The Times, Review, Saturday 18 November 2023, p.20. Image only, see: [WIKI LANGLEY PRINCES DOC_ THETIMES CRITICS CHOICE_18 NOV 2023.jpg]

- ^ The Princes in the Tower: The New Evidence Brinkworth Productions. Retrieved 20 May 2024. https://www.brinkworth.tv/shows/the-princes-in-the-tower-the-new-evidence/

- ^ "Princes in the Tower – History is Being Rewritten" (PDF) (Press release). Richard III Society. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Maula, Zoë; Roefstra, Jean; Wiss, William (June 2024). "Dutch statement on The Missing Princes Project". The Ricardian Bulletin. p. 4.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (June 2024). "A reply from Philippa Langley". The Ricardian Bulletin. p. 4.

- ^ Hicks, Michael (June 2024). "More proof needed on Princes". The Ricardian Bulletin. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (June 2024). "In response to Michael Hicks". The Ricardian Bulletin. p. 5.

- ^ Benno von Wiese: Friedrich Schiller (in German) Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1959, pp. 781–786.

- ^ "Friedrich Schiller – Nachlass – II. Warbeck – Personen". Kuehnle-online.de. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Rosemary Hawley Jarman, We Speak No Treason, Book 1, Part Two

- ^ Smith, Anne Easter, The King's Grace

- ^ "🎧 the Pretender".

- ^ Llewellyn Smith, Julia (17 November 2023). "'Historians said I was unhinged': Philippa Langley cracks mystery of princes in the tower". The Times. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Ashley, Mike (2002). British Kings & Queens. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1104-3. pp. 231–232.

- Bain, Joseph, ed., Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland, 1357–1509, vol. 4, HM Register House, Edinburgh (1888)

- Busch, Wilhelm, "England Under the Tudors," 1892. pp. 440–441.

- Treasury, Scotland (1877). Compota Thesaurariorum Regum Scotorum. Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland 1473–1574.

- Dunlop, David, 'The 'Masked Comedian': Perkin Warbeck's Adventures in Scotland and England from 1495 to 1497,' Scottish Historical Review, vol. 70, no. 90, (Oct. 1991), 97–128.

- Ford, John, ed. Ure, Peter. "The chronicle history of Perkin Warbeck: a strange truth". London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1968.

- Gairdner, James. "History of the life and reign of Richard the Third : to which is added the story of Perkin Warbeck. From original documents, by James Gairdner". Cambridge, 1898. New York: Kraus Reprint Co., 1968.

- Guy, John. "Tudor England" p52 et seq.

- Macdougall, Norman, James the Fourth, Tuckwell (1997)

- Pinkerton, John (1797). The History of Scotland From The Accession of the House of Stuart To That of Mary: With Appendixes of Original Papers. In Two Volumes. Dilly.

- Stevenson, Katie, Chivalry in Scotland, CUP/Boydell (2006), p. 84.

- Weir, Alison (21 September 2011). The Princes in the Tower. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-80684-0.

- Wroe, Ann. Perkin: A Story of Deception. Vintage: 2004 (ISBN 0-09-944996-X).

External links

[edit]- Perkin Warbeck

- People from the Burgundian Netherlands

- 1470s births

- 1499 deaths

- 1490s in England

- 1490s in Scotland

- 15th-century executions by England

- Executed Belgian people

- Court of James IV of Scotland

- House of York

- Impostor pretenders

- Military history of Cornwall

- People executed at Tyburn

- People executed by the Kingdom of England by hanging

- People executed under Henry VII of England

- People from Tournai

- People of the Tudor period

- Pretenders to the English throne

- Prisoners in the Tower of London

- 15th-century people from the Holy Roman Empire

- Burials at Austin Friars, London

- Belgian expatriates in England

- Princes in the Tower