Northwest Territories

Northwest Territories

| |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 67°N 121°W / 67°N 121°W[2] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Before confederation | British Arctic Territories, North-Western Territory, Rupert's Land |

| Confederation | July 15, 1870[note 1] (5th, with Manitoba) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Yellowknife |

| Largest metro | Yellowknife |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary system, with consensus government |

| • Commissioner | Gerald Kisoun |

| • Premier | R. J. Simpson |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 1 of 338 (0.3%) |

| Senate seats | 1 of 105 (1%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,346,106 km2 (519,734 sq mi) |

| • Land | 1,183,085 km2 (456,792 sq mi) |

| • Water | 163,021 km2 (62,943 sq mi) 12.1% |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| 13.5% of Canada | |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 41,070[3] |

| • Estimate (Q3 2024) | 44,731[5] |

| • Rank | 11th |

| • Density | 0.03/km2 (0.08/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Northwest Territorian[6] FR: Franco-Ténois(e) |

| Official languages |

|

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 11th |

| • Total (2017) | C$4.856 billion[9] |

| • Per capita | C$108,065 (1st) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2021) | 0.930[10]—Very high (4th) |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 |

| Canadian postal abbr. | NT |

| Postal code prefix | |

| ISO 3166 code | CA-NT |

| Flower | Mountain avens |

| Tree | Tamarack larch |

| Bird | Gyrfalcon |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated NT or NWT; French: Territoires du Nord-Ouest; formerly North-West Territories) is a federal territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately 1,127,711.92 km2 (435,412.01 sq mi) and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of the three territories in Northern Canada.[3] Its estimated population as of the second quarter of 2024 is 44,920.[5] Yellowknife is the capital, most populous community, and the only city in the territory; its population was 20,340 as of the 2021 census. It became the territorial capital in 1967, following recommendations by the Carrothers Commission.

The Northwest Territories, a portion of the old North-Western Territory, entered the Canadian Confederation on July 15, 1870. At first, it was named the North-West Territories. The name was changed to the present Northwest Territories in 1906.[11] Since 1870, the territory has been divided four times to create new provinces and territories or enlarge existing ones. Its current borders date from April 1, 1999, when the territory's size was decreased again by the creation of a new territory of Nunavut to the east, through the Nunavut Act and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement.[12][13] While Nunavut is mostly Arctic tundra, the Northwest Territories has a slightly warmer climate and is both boreal forest (taiga) and tundra, and its most northern regions form part of the Arctic Archipelago.

The Northwest Territories has the most interprovincial and inter-territorial land borders among all provinces and territories of Canada. It is bordered by the territories of Nunavut to the east and Yukon to the west, and by the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan to the south; it also touches Manitoba to the southeast at a quadripoint that includes Nunavut and Saskatchewan. The land area of the Northwest Territories is roughly equal to that of France, Portugal and Spain combined, although its overall area is even larger because of its vast lakes.

Name

[edit]The name was originally descriptive, adopted by the British government during the colonial era to indicate where it lay in relation to the rest of Rupert's Land. It has been shortened from North-Western Territory and then North-West Territories.

In Inuktitut, the Northwest Territories are referred to as Nunatsiaq (Inuktitut syllabics ᓄᓇᑦᓯᐊᖅ), "beautiful land".[14] The northernmost region of the territory is home to the Inuvialuit, who primarily live in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Inuvialuit Nunangit Sannaiqtuaq), while the southern portion is called Denendeh (an Athabaskan word meaning "our land"). Denendeh is the vast Dene country, stretching from central Alaska to Hudson Bay, within which lie the homelands of the numerous Dene nations.

Since the Yukon Territory was split from it in 1898, it is no longer the westernmost territory, and until Nunavut was split from it in 1999 it included territory extending as far east as Canada's Atlantic provinces.[15][16][17] There has been some discussion of changing the name, possibly to a term from an Indigenous language. One proposal was "Denendeh", as advocated by the former premier Stephen Kakfwi, among others.[18] One of the most popular proposals for a new name—to name the territory "Bob"—began as a prank, but for a while it was at or near the top in the public-opinion polls.[19][20][21]

Geography

[edit]

Located in northern Canada, the territory borders Canada's two other territories, Yukon to the west and Nunavut to the east, as well as four provinces: British Columbia to the southwest, Alberta and Saskatchewan to the south, and Manitoba (through a quadripoint) to the extreme southeast. It has a land area of 1,183,085 km2 (456,792 sq mi).[4]

Geographical features include Great Bear Lake, the largest lake entirely within Canada,[22] and Great Slave Lake, the deepest body of water in North America at 614 m (2,014 ft), as well as the Mackenzie River and the canyons of the Nahanni National Park Reserve, a national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. Territorial islands in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago include Banks Island, Borden Island, Prince Patrick Island, and parts of Victoria Island and Melville Island. Its highest point is Mount Nirvana near the border with Yukon at an elevation of 2,773 m (9,098 ft).

Climate

[edit]

The Northwest Territories extends for more than 1,300,000 km2 (500,000 sq mi) and has a large climate variance from south to north. The southern part of the territory (most of the mainland portion) has a subarctic climate, while the islands and northern coast have a polar climate.[citation needed]

Summers in the north are short and cool, featuring daytime highs of 14–17 °C (57–63 °F) and lows of 1–5 °C (34–41 °F). Winters are long and harsh, with daytime highs of −20 to −25 °C (−4 to −13 °F) and lows of −30 to −35 °C (−22 to −31 °F). The coldest nights typically reach −40 to −45 °C (−40 to −49 °F) each year.[citation needed]

Extremes are common, with summer highs in the south reaching 36 °C (97 °F) and lows reaching below 0 °C (32 °F). In winter in the south, it is not uncommon for the temperatures to reach −40 °C (−40 °F), but they can also reach the low teens during the day. In the north, temperatures can reach highs of 30 °C (86 °F), and lows into the low negatives. In winter in the north, it is not uncommon for the temperatures to reach −50 °C (−58 °F) but they can also reach single digits during the day.[citation needed]

Thunderstorms are not rare in the south. In the north, they are very rare but do occur.[23] Tornadoes are extremely rare but have happened with the most notable one happening[when?] just outside Yellowknife that destroyed a communications tower.[citation needed] The Territory has a fairly dry climate due to the mountains in the west.[citation needed]

About half of the territory is above the tree line. There are not many trees in most of the eastern areas of the territory, or in the north islands.[24]

| City | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fort Simpson[25] | 24/11 | 75/52 | −20/−29 | −4/−19 |

| Yellowknife[26] | 21/13 | 70/55 | −22/−30 | −7/−21 |

| Inuvik[27] | 20/9 | 67/48 | −23/−31 | −9/−24 |

| Sachs Harbour[28] | 10/3 | 50/38 | −24/−32 | −12/−25 |

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

There are multiple Indigenous territories overlapping the current borders of the Northwest Territories. These include Denendeh,[29] Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Inuvialuit Nunangit Sannaiqtuaq), and both Métis and Nêhiyawak countries (Michif Piyii[30] and ᓀᐦᐃᔮᓈᕁ nêhiýânâhk,[31] respectively). Of these, Denendeh and the Dene nations are the most prominent with the rest of the Dene country ("Dene-ndeh" or Deneland) covering much of what is now Alaska, British Columbia, and the northern regions of the prairie provinces.[32] Some of its constituent territories include Tłı̨chǫ Country, Got'iné Néné, Dehchondéh, and Gwichʼin Nành, amongst others including those of the Dënë Sųłinë́ (Nëné, "land"), Dane-z̲aa (Nanéʔ), and the T'satsąot'ınę (Ndé). Historically, Dene have lived across Denendeh and what is now the NWT since time immemorial and the era of Yamoria and Yamozha.[33][34]

Along the northern coast live one of the Inuit sudivisions: the Inuvialuit, a conglomerate of several Inuvialuit peoples, including the Uummarmiut, Kangiryuarmiut, and Siglit. Their country, variously called Inuvialuit Nunangit, Inuvialuit Nunungat, or Inuvialuit Nunangat corresponds to the Inuvialuit Settlement Region and belongs to the greater Inuit Nunangat.[35] Amongst the other Inuit, there are also the Copper Inuit who inhabit their traditional territory, Inuinnait Nunangat, between the Kitikmeot and Inuvik Regions.[36] To the south are the Cree First Nations and Métis.

In 1670, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) was formed from a royal charter, and was granted a commercial monopoly over Rupert's Land. Present day Northwest Territories laid northwest of Rupert's Land, and was known as the North-Western Territory. Although not formally part of Rupert's Land, the HBC made regular use of the region as a part of its trading area. The Treaty of Utrecht saw the British become the only European power with practical access to the North-Western Territory, with the French surrendering their claim to the Hudson Bay coast.

Europeans have visited the region for the purposes of fur trading, and exploration for new trade routes, including the Northwest Passage. Arctic expeditions launched in the 19th century include the Coppermine expedition.

In 1867, the first Canadian residential school opened in the region in Fort Resolution. The opening of the school was followed by several others in regions across the territory, thus contributing to it reaching the highest percentage of students in residential schools compared to other area in Canada.[37]

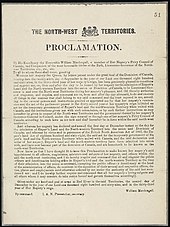

The present-day territory came under the authority of the Government of Canada in July 1870, after the Hudson's Bay Company transferred Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to the British Crown, which subsequently transferred them to Canada, giving it the name the North-West Territories. This immense region comprised all of today's Canada except British Columbia, an early form of Manitoba (a small square area around Winnipeg), early forms of present-day Ontario and Quebec (the coast of the Great Lakes, the Saint Lawrence River valley and the southern third of modern Quebec), the Maritimes (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick), Newfoundland, the Labrador coast, and the Arctic Islands (except the southern half of Baffin Island).[38]

After the 1870 transfer, some of the North-West Territories was whittled away. The province of Manitoba was enlarged in 1881 to a rectangular region composing the modern province's south. By the time British Columbia joined Confederation on July 20, 1871, it had already (1866) been granted the portion of North-Western Territory south of 60 degrees north and west of 120 degrees west, an area that comprised most of the Stickeen Territories (and a portion of the Peace River country).[citation needed]

The North-West Territories Council was created in 1875 for more local government in the North-West Territories.[39] At first wholly made up of appointed members, it got its first elected members in 1882 and became wholly elected in 1888 when the council was reorganized as the Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories. Frederick Haultain, an Ontario lawyer who practised at Fort Macleod from 1884, became its chairman in 1891 and Premier when the Assembly was reorganized in 1897. The modern provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta were created in 1905. Contemporary records show Haultain recommended that the NWT become a single province, named Buffalo, but the Canadian government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier acted otherwise.[40][41]

In the meantime, the British Arctic Territories were transferred to Canada and added to the North-West Territories in 1880. The province of Ontario was enlarged north-westward in 1882. Quebec was also extended northwards in 1898. Yukon was also made a separate territory that year and eventually gained additional territorial powers with the 2003 Yukon Act.[42] One year after the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were created in 1905, the Parliament of Canada renamed the "North-West Territories" as the Northwest Territories, dropping all hyphenated forms of it.[43][44]

Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec acquired the last addition to their modern landmass from the Northwest Territories in 1912. This left only the districts of Mackenzie, Franklin (which absorbed the remnants of Ungava in 1920) and Keewatin within what was then given the name Northwest Territories. In 1925, the boundaries of the Northwest Territories were extended all the way to the North Pole on the sector principle, vastly expanding its territory onto the northern ice cap.[citation needed] Between 1925 and 1999, the Northwest Territories covered a land area of 3,439,296 km2 (1,327,920 sq mi)—larger than one-third of Canada in terms of area.[citation needed]

On April 1, 1999, a separate Nunavut territory was formed from the eastern Northwest Territories to represent the Inuit.[45]

Demography

[edit]Visible minority and indigenous identity (2016):[46][47]

The NWT is one of two jurisdictions in Canada – Nunavut being the other – where Indigenous peoples are in the majority, constituting 50.4% of the population.[48]

According to the 2016 Canadian census, the 10 major ethnic groups were:[49]

Language

[edit]

French was made an official language in 1877 by the then-territorial government. After a lengthy and bitter debate resulting from a speech from the throne in 1888 by Lieutenant Governor Joseph Royal, the members of the time voted on more than one occasion to nullify this and make English the only language used in the assembly. After some conflict with the Confederation Government in Ottawa, and a decisive vote on January 19, 1892, the assembly members voted for an English-only territory.

Currently, the Northwest Territories' Official Languages Act recognizes the following eleven official languages:[7][8]

NWT residents have a right to use any of the above languages in a territorial court, and in the debates and proceedings of the legislature. However, the laws are legally binding only in their French and English versions, and the NWT government only publishes laws and other documents in the territory's other official languages when the legislature asks it to. Furthermore, access to services in any language is limited to institutions and circumstances where there is a significant demand for that language or where it is reasonable to expect it given the nature of the services requested. In practical terms, English language services are universally available, and there is no guarantee that other languages, including French, will be used by any particular government service, except for the courts.

The 2016 census returns showed a population of 41,786. Of the 40,565 singular responses to the census question regarding each inhabitant's "mother tongue", the most reported languages were the following (italics indicate an official language of the NWT):

| 1 | English | 31,765 | 78.3% |

| 2 | Dogrib (Tłı̨chǫ) | 1,600 | 3.9% |

| 3 | French | 1,175 | 2.9% |

| 4 | South Slavey | 775 | 1.9% |

| 5 | North Slavey | 745 | 1.8% |

| 6 | Tagalog | 745 | 1.8% |

| 7 | Inuinnaqtun | 470 | 1.1% |

| 8 | Dené | 440 | 1.1% |

| 9 | Slavey (not otherwise specified) | 175 | 0.4% |

| 10 | Gwich'in | 140 | 0.3% |

| 11 | Cree | 130 | 0.3% |

There were also 630 responses of both English and a "non-official language"; 35 of both French and a "non-official language"; 145 of both English and French, and about 400 people who either did not respond to the question, or reported multiple non-official languages, or else gave some other unenumerable response. (Figures shown are for the number of single language responses and the percentage of total single-language responses.)[50]

Religion

[edit]In the 2021 Census, 55.2% of the population followed Christianity (primarily Roman Catholicism); this is down from 67.6% in the 2001 Census. At the same time, the population reported having no religious affiliation has more than doubled, from 17.4% in 2001 to 39.8% in 2021 census. About 5.0% reported other religious affiliations.[51][52]

Communities

[edit]| Municipality | 2016 |

|---|---|

| Yellowknife[53] | 19,569 |

| Hay River[54] | 3,528 |

| Inuvik[55] | 3,243 |

| Fort Smith[56] | 2,542 |

| Behchokǫ̀[57] | 1,874 |

As of 2014, there are 33 official communities in the NWT.[58] These range in size from Yellowknife with a population of 19,569[53] to Kakisa with 36 people.[59] Governance of each community differs, some are run under various types of First Nations control, while others are designated as a city, town, village or hamlet, but most communities are municipal corporations.[58][60] Yellowknife is the largest community and has the largest number of Aboriginal peoples, 4,520 (23.4%) people.[61] However, Behchokǫ̀, with a population of 1,874,[62] is the largest First Nations community, 1,696 (90.9%),[63] and Inuvik with 3,243 people[64] is the largest Inuvialuit community, 1,315 (40.5%).[65] There is one Indian reserve in the NWT, Hay River Reserve, located on the south shore of the Hay River.

Economy

[edit]The gross domestic product of the Northwest Territories was C$4.856 billion in 2017.[66] It has the highest per capita GDP of all provinces and territories in Canada, totalling C$76,000 in 2009.[67]

Mining

[edit]The Territories' geological resources include gold, diamonds, natural gas and petroleum. BP is the only oil company currently producing oil there. Its diamonds are promoted as an alternative to purchasing blood diamonds.[68] Two of the biggest mineral resource companies in the world, BHP and Rio Tinto mine many of their diamonds there. In 2010, Territories' accounted for 28.5% of Rio Tinto's total diamond production (3.9 million carats, 17% more than in 2009, from the Diavik Diamond Mine) and 100% of BHP's (3.05 million carats from the EKATI mine).[69][70]

The Eldorado Mine produced uranium for the Manhattan Project, as well as radium, silver, and copper (for other uses).

- Eldorado Mine – 1933–1940, 1942–1960, 1976–1982 (radium, uranium, silver, copper)

- Con Mine – 1938–2003 (gold)

- Negus Mine – 1939–1952 (gold)

- Ptarmigan and Tom Mine – 1941–1942, 1986–1997 (gold)

- Thompson-Lundmark Mine – 1941–1943, 1947–1949 (gold)

- Giant Mine – 1948–2004 (gold)

- Discovery Mine – 1950–1969 (gold)

- Rayrock Mine – 1957–1959 (uranium)

- Camlaren Mine – 1962–1963, 1980–1981 (gold)

- Cantung Mine – 1962–1986, 2002–2003, 2005–2015 (tungsten)

- Echo Bay Mines – 1964–1975 (silver and copper)

- Pine Point Mine – 1964–1988 (lead and zinc)

- Tundra Mine – 1964–1968 (gold)

- Terra Mine – 1969–1985 (silver and copper)

- Salmita Mine – 1983–1987 (gold)

- Colomac Mine – 1990–1992, 1994–1997 (gold)

- Ekati Diamond Mine – 1998–current (diamonds)

- Diavik Diamond Mine – 2003–current (diamonds)

- Snap Lake Diamond Mine – 2007–2015 (diamonds)

Tourism

[edit]

During the winter, many international visitors go to Yellowknife to watch the auroras. Five areas managed by Parks Canada are situated within the territory: Aulavik and Tuktut Nogait National Parks are in the northern part. Portions of Wood Buffalo National Park are located within it, although most of it is located in neighbouring Alberta. Parks Canada also manages three park reserves: Nááts'ihch'oh, Nahanni National Park Reserve, and Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve.

Government

[edit]

As a territory, the NWT has fewer rights than the provinces. During his term, Premier Kakfwi pushed to have the federal government accord more rights to the territory, including having a greater share of the returns from the territory's natural resources go to the territory.[71] Devolution of powers to the territory was an issue in the 20th general election in 2003, and has been ever since the territory began electing members in 1881.

The Commissioner of the NWT is the chief executive and is appointed by the Governor-in-Council of Canada on the recommendation of the federal Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development. The position used to be more administrative and governmental, but with the devolution of more powers to the elected assembly since 1967, the position has become symbolic. The commissioner had full governmental powers until 1980 when the territories were given greater self-government. The legislative assembly then began electing a cabinet and government leader, later known as the premier. Since 1985 the commissioner no longer chairs meetings of the executive council (or cabinet), and the federal government has instructed commissioners to behave like a provincial lieutenant governor. Unlike lieutenant governors, the Commissioner of the Northwest Territories is not a formal representative of the King of Canada.[citation needed]

Unlike provincial governments and the government of Yukon, the government of the Northwest Territories does not have political parties. It never has had political parties except for the period between 1898 and 1905. Its legislative assembly operates through the consensus government model. The website of the NWT government describes consensus government thusly: "The Northwest Territories is one of only two jurisdictions in Canada with a consensus system of government instead of one based on party politics. In our system, all Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) are elected as independents. Shortly after the election, all Members meet as a Caucus to set priorities for that Assembly. The Caucus remains active throughout their term as the forum where all Members meet as equals.[...] Compared to the party system, there is much more communication between Regular Members and Cabinet. All legislation, major policies, and proposed budgets pass through the Regular Members' standing committees before coming to the House."[72]

The NWT Legislative Assembly is composed of one member elected from each of the nineteen constituencies. After each general election, the new assembly elects the premier and the speaker by secret ballot. Seven MLAs are also chosen as cabinet ministers, with the remainder forming the opposition.

The membership of the current legislative assembly was set by the 2023 Northwest Territories general election on November 14, 2023. R.J. Simpson was selected as the new premier by his fellow MLAs on December 7, 2023.[73]

The member of Parliament for the Northwest Territories is Michael McLeod (Liberal Party). The Commissioner of the Northwest Territories is Gerald Kisoun.

In the Parliament of Canada, the NWT comprises a single Senate division and a single House of Commons electoral district, titled Northwest Territories (Western Arctic until 2014). Thus a single MP represents an area that is almost 14 percent of the land area of all of Canada.

Departments

[edit]The government of Northwest Territories comprises the following departments:[74]

- Education, Culture and Employment

- Environment and Climate Change

- Executive and Indigenous Affairs

- Finance

- Health and Social Services

- Industry, Tourism and Investment

- Infrastructure

- Justice

- Legislative Assembly

- Municipal and Community Affairs

Administrative regions

[edit]

The Northwest Territories is divided into five administrative regions (regional offices in parentheses):

- Dehcho Region (Fort Simpson)[75]

- Inuvik Region (Inuvik)[76]

- North Slave Region (Yellowknife and Behchoko [sub-office])[77]

- Sahtu Region (Norman Wells)[78]

- South Slave Region (Fort Smith and Hay River [sub-office])[79]

Culture

[edit]

Aboriginal issues in the Northwest Territories include the fate of the Dene who, in the 1940s, were employed to carry radioactive uranium ore from the mines on Great Bear Lake. Of the thirty plus miners who worked at the Port Radium site, at least fourteen have died due to various forms of cancer. A study was done in the community of Deline, called A Village of Widows by Cindy Kenny-Gilday, which indicated that the number of people involved were too small to be able to confirm or deny a link.[80][81]

There has been racial tension based on a history of violent conflict between the Dene and the Inuit,[82] who have now taken recent steps towards reconciliation.

Land claims in the NWT began with the Inuvialuit Final Agreement, signed on June 5, 1984. It was the first Land Claim signed in the Territory, and the second in Canada.[83] It culminated with the creation of the Inuit homeland of Nunavut, the result of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, the largest land claim in Canadian history.[84]

Another land claims agreement with the Tłı̨chǫ people created a region within the NWT called Tli Cho, between Great Bear and Great Slave Lakes, which gives the Tłı̨chǫ their own legislative bodies, taxes, resource royalties, and other affairs, though the NWT still maintains control over such areas as health and education. This area includes two of Canada's three diamond mines, at Ekati and Diavik.[85]

Festivals

[edit]Among the festivals in the region are the Great Northern Arts Festival, the Snowking Winter Festival, Folk on the Rocks music festival in Yellowknife, and Rockin the Rocks.

Transportation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Road

[edit]

Northwest Territories has nine numbered highways. The longest is the Mackenzie Highway, which stretches from the Alberta Highway 35's northern terminus in the south at the Alberta – Northwest Territories border at the 60th parallel to Wrigley, Northwest Territories in the north. Ice roads and winter roads are also prominent and provide road access in winter to towns and mines which would otherwise be fly-in locations. Yellowknife Highway branches out from Mackenzie Highway and connects it to Yellowknife. Dempster Highway is the continuation of Klondike Highway. It starts just west of Dawson City, Yukon, and continues east for over 700 km (430 mi) to Inuvik. As of 2017, the all-season Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk Highway connects Inuvik to communities along the Arctic Ocean as an extension of the Dempster Highway.

Yellowknife did not have an all-season road access to the rest of Canada's highway network until the completion of Deh Cho Bridge in 2012. Prior to that, traffic relied on ferry service in summer and ice road in winter to cross the Mackenzie River. This became a problem during spring and fall time when the ice was not thick enough to handle vehicle load but the ferry could not pass through the ice, which would require all goods from fuel to groceries to be airlifted during the transition period.

The Northwest Territories is the only jurisdiction in North America to issue a non rectangular standard licence plate. Instead, the territory issues a licence plate shaped like a polar bear.

Public transit

[edit]Yellowknife Transit is the public transportation agency in the city, and is the only transit system within the Northwest Territories.[86]

Air

[edit]

Yellowknife Airport is the largest airport in the territory in terms of aircraft movements and passengers. It is the gateway airport to other destinations within the Northwest Territories. As the airport of the territory capital, it is part of the National Airports System. It is the hub of multiple regional airlines. Major airlines serving destinations within Northwest Territories include Buffalo Airways, Canadian North, North-Wright Airways.

See also

[edit]- List of National Parks of Canada

- List of Northwest Territories Legislative Assemblies

- List of Northwest Territories plebiscites

- List of ghost towns in the Northwest Territories

- Scouting and Guiding in the Northwest Territories

- Symbols of the Northwest Territories

- Education in the Northwest Territories

- List of people from the Northwest Territories

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ceded to Canada by the Hudson's Bay Company.

References

[edit]- ^ Government of Canada, Natural Resources Canada. "Place names - Territoires du Nord-Ouest". www4.rncan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ "Northwest Territories". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b "Land and freshwater area, by province and territory". February 1, 2005. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ a b "Population estimates, quarterly". Statistics Canada. September 27, 2023. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ The terms Northwest Territorian(s) Hansard, Thursday, March 25, 2004 Archived March 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, and (informally) NWTer(s) Hansard, Monday, October 23, 2006 Archived March 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, occur in the official record of the territorial legislature Archived June 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. According to the Oxford Guide to Canadian English Usage (ISBN 978-0-19-541619-0; p. 335), there is no common term for a resident of Northwest Territories.

- ^ a b "Official Languages Act (Northwest Territories" (PDF). Government of the Northwest Territories. 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Official Languages of the Northwest Territories". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory (2017)". Statistics Canada. September 17, 2019. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ "History of the Name of the Northwest Territories". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ Justice Canada (1993). "Nunavut Act". Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ Justice Canada (1993). "Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act". Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ Izenberg, Dafna (Summer 2005). "The Conscience of Nunavut". Ryerson Review of Journalism (Online). Toronto: Ryerson School of Journalism. ISSN 0838-0651. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ Hopper, Tristin (February 28, 2018). "Why the Northwest Territories desperately need a name change". National Post. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Northwest Territories". Wordorigins.org. July 15, 2021. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Canada's Northwest Territories Travel Guide". The Art of Travel: Wander, Explore, Discover. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Tundra for two: dividing Canada's far-north is no small task". Archived from the original on April 5, 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Northwest Territories looking for new name – "Bob" need not apply". Canada: CBC. January 11, 2002. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Western Arctic to Northwest Territories: MP calls for riding name change". Canada: CBC. June 25, 2008. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ Jon Willing. "What about Bob, Water-Lou?". Archived from the original on January 18, 2003. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Top 10 Lakes – Great Bear Lake". Archived from the original on May 30, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Maybank, J. (2012). "Thunderstorm". The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Historica-Dominion Institute. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Publications & Maps". Globalforestwatch.org. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Fort Simpson A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2202101. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Yellowknife A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2204100. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Inuvik A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2202570. Archived from the original on November 3, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Sachs Harbour A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Climate ID: 2503650. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Home". Dene Nation. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Michif Piyii". native-land.ca. Archived from the original on October 18, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "country". Plains Cree Dictionary. Algonquin Dictionaries Project. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Dënéndeh". native-land.ca. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Yamǫǫ̀zha - Dene Laws". Tlicho History. Tłı̨chǫ Government. Archived from the original on October 5, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ Campbell, Daniel. "The Hero of the Dene". Up Here Publishing. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Inuit Nunangat Map". www.itk.ca. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. April 4, 2019. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ McGhee, Robert (March 4, 2015). "Inuinnait (Copper Inuit)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on March 15, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Residential Schools Education" (PDF). www.ece.gov.nt.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Canadian Heritage – Northwest Territories". Pch.gc.ca. July 13, 2010. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ The North-West Territories Act, 1875, SC 1875, c. 49, s. 3, 7.

- ^ Alberta Online Encyclopedia biography of Frederick Haultain

- ^ Mardon and Mardon, Alberta Election Results, 1882-1992, p. 195

- ^ Tattrie, Jon. "Yukon and Confederation". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "History of the Name of the Northwest Territories". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "c.62, RSC 1906". 1906.

- ^ "Creation of a new Northwest Territories". Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. November 6, 2012. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Aboriginal Peoples Highlight Tables". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Canada 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Statistics Canada. "Ethnic origin population". Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (February 8, 2017). "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Northwest Territories [Territory] and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Selected Religions, for Canada, Provinces and Territories – 20% Sample Data". 2.statcan.ca. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "In 2021, more than half of the population of British Columbia and Yukon reported having no religion, while the Christian religion was predominant in the other provinces and territories". October 26, 2022. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "2011 Community Profiles – Hay River". www12.statcan.ca. November 29, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "2016 Community Profiles – Hay River". www12.statcan.ca. November 29, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "2011 Community Profiles – Fort Smith". www12.statcan.ca. November 29, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Census Profile". October 6, 2020. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ a b "Communities". Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Differences in Community Government Structures" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Yellowknife [Census agglomeration]". Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Census Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Behchokò – Aboriginal population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Census Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "search: Inuvik". www12.statcan.gc.ca. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Statistics Canada (2018). "Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0222-01 Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, provincial and territorial, annual (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. doi:10.25318/3610022201-eng. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Government of the Northwest Territories: Industry, Tourism and Investment. "Did You Know?". Archived from the original on July 31, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ "BHP Billiton diamond marketing". Bhpbilliton.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Rio Tinto 4th quarter 2010 Operations" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ "BHP Billiton 2010 Annual Report page 124" (PDF). 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ "NWT Premier asks provincial leaders for backing". Globeandmail.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "What is Consensus Government? | Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories". November 6, 2012. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Government of the NWT Archived July 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved August 7, 2023

- ^ "Dehcho Region". Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Inuvik Region". Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "North Slave Region". Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Sahtu Region". Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "South Slave Region". Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "A Village of Widows". Arcticcircle.uconn.edu. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Echoes of the Atomic Age". Ccnr.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Relations with their Southern Neighbours". Archived from the original on February 29, 2000. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "IRC: Inuvialuit Final Agreement". Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "Agreement between the Inuit of the Nunavut Settlement Area and Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Canada" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ "Government of the NWT news release on land claims signing". Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Transit Route Analysis Study Final Report" (PDF). City of Yellowknife. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Coates, Kenneth (1985). Canada's colonies: a history of the Yukon and Northwest Territories. Lorimer. ISBN 978-0-88862-931-9. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Choquette, Robert (1995). The Oblate assault on Canada's northwest. University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0-7766-0402-2.

Northwest Territories.

- Ecosystem Classification Group, and Northwest Territories. Ecological Regions of the Northwest Territories Taiga Plains[permanent dead link]. Yellowknife, NWT: Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources, Govt. of the Northwest Territories, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7708-0161-8

External links

[edit]- Government of the Northwest Territories

- Northwest Territories Tourism Archived February 3, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre Archived May 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Aurora College Archived May 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- NWT Archives Archived May 31, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- NWT Literacy Council

- Language Commissioner of the Northwest Territories

- Lessons From the Land: interactive journeys of NWT traditional Aboriginal trails

- CBC Digital Archives – Northwest Territories: Voting in Canada's North Archived June 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Northwest Territories Act