Criticism of the Federal Reserve

| Public finance |

|---|

|

The Federal Reserve System, commonly known as "the Fed," has faced various criticisms since its establishment in 1913. Critics have questioned its effectiveness in managing inflation, regulating the banking system, and stabilizing the economy. Notable critics include Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman and his fellow monetarist Anna Schwartz, who argued that the Fed's policies exacerbated the Great Depression. More recently, former Congressman Ron Paul has advocated for the abolition of the Fed and a return to a gold standard.[1]

Critics have also raised concerns about the Fed's role in fractional reserve banking, its contribution to economic cycles, and its transparency. The Fed has been accused of causing economic downturns, including the 2007-2008 financial crisis,[2] and of being influenced by private interests. Despite these criticisms, the Federal Reserve remains a central institution in the United States' financial system, with ongoing debates about its role, policies, and the need for reform.

Creation

[edit]An early version of the Federal Reserve Act was drafted in 1910 on Jekyll Island, Georgia, by Republican Senator Nelson Aldrich, chairman of the National Monetary Commission, and several Wall Street bankers. The final version, with provisions intended to improve public oversight and weaken the influence of the New York banking establishment, was drafted by Democratic Congressman Carter Glass of Virginia.[3] The structure of the Fed was a compromise between the desire of the bankers for a central bank under their control and the desire of President Woodrow Wilson to create a decentralized structure under public control.[4] The Federal Reserve Act was approved by Congress and signed by President Wilson in December 1913.[4]

Inflation policy

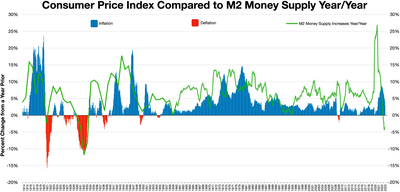

[edit]In The Case Against the Fed, Murray Rothbard argued in 1994 that, although a supposed core function of the Federal Reserve is to maintain a low level of inflation, its policies (like those of other central banks) have actually aggravated inflation. This occurs when the Fed creates too much fiat money backed by nothing. He called the Fed policy of money creation "legalized counterfeiting" and favored a return to the gold standard.[5] He wrote:

[I]t is undeniable that, ever since the Fed was visited upon us in 1914, our inflations have been more intense, and our depressions far deeper, than ever before. There is only one way to eliminate chronic inflation, as well as the booms and busts brought by that system of inflationary credit: and that is to eliminate the counterfeiting that constitutes and creates that inflation. And the only way to do that is to abolish legalized counterfeiting: that is, to abolish the Federal Reserve System, and return to the gold standard, to a monetary system where a market-produced metal, such as gold, serves as the standard money, and not paper tickets printed by the Federal Reserve.[6]

Effectiveness and policies

[edit]The Federal Reserve has been criticized as not meeting its goals of greater stability and low inflation.[7] This has led to a number of proposed changes including advocacy of different policy rules[8] or dramatic restructuring of the system itself.[9]

Milton Friedman concluded that while governments do have a role in the monetary system[10] he was critical of the Federal Reserve due to its poor performance and felt it should be abolished.[11][12] Friedman believed that the Federal Reserve System should ultimately be replaced with a computer program.[9] He favored a system that would automatically buy and sell securities in response to changes in the money supply.[13] This proposal has become known as Friedman's k-percent rule.[14]

Others have proposed NGDP targeting as an alternative rule to guide and improve central bank policy.[15][16] Prominent supporters include Scott Sumner,[17] David Beckworth,[18] and Tyler Cowen.[19]

Congress

[edit]Several members of Congress have criticized the Fed. Senator Robert Owen, whose name was on the Glass-Owen Federal Reserve Act, believed that the Fed was not performing as promised. He said:

The Federal Reserve Board was created to control, regulate and stabilize credit in the interest of all people. . . . The Federal Reserve Board is the most gigantic financial power in all the world. Instead of using this great power as the Federal Reserve Act intended that it should, the board . . . delegated this power to the banks.[20][21]

Representative Louis T. McFadden, Chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Currency from 1920 to 1931, accused the Federal Reserve of deliberately causing the Great Depression. In several speeches made shortly after he lost the chairmanship of the committee, McFadden claimed that the Federal Reserve was run by Wall Street banks and their affiliated European banking houses. In one 1932 House speech (that has been criticized as bluster[22]), he stated:

Mr. Chairman, we have in this country one of the most corrupt Institutions the world has ever known. I refer to the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve banks; . . . This evil institution has impoverished and ruined the people of the United States . . . through the corrupt practices of the moneyed vultures who control it.[23]

Many members of Congress who have been involved in the House and Senate Banking and Currency Committees have been open critics of the Federal Reserve, including Chairmen Wright Patman,[24] Henry Reuss,[25] and Henry B. Gonzalez. Representative Ron Paul, Chairman of the Monetary Policy Subcommittee in 2011, is known as a staunch opponent of the Federal Reserve System.[26] He routinely introduced bills to abolish the Federal Reserve System,[27] three of which gained approval in the House but lost in the Senate.[28]

Congressman Paul also introduced H.R. 459: Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2011,[29][30] This act required an audit of the Federal Reserve Board and the twelve regional banks, with particular attention to the valuation of its securities. His son, Senator Rand Paul, has introduced similar legislation in subsequent sessions of Congress.[31]

Great Depression (1929)

[edit]

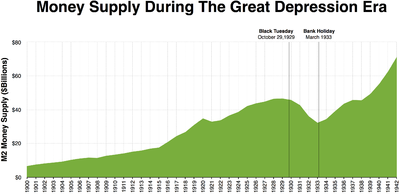

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz stated that the Fed pursued an erroneously restrictive monetary policy, exacerbating the Great Depression. After the stock market crash in 1929, the Fed continued its contraction (decrease) of the money supply and refused to save banks that were struggling with bank runs. This mistake, critics charge, allowed what might have been a relatively mild recession to explode into catastrophe. Friedman and Schwartz believed that the depression was "a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces."[32] Before the establishment of the Federal Reserve, the banking system had dealt with periodic crises (such as in the Panic of 1907) by suspending the convertibility of deposits into currency. In 1907, the system nearly collapsed and there was an extraordinary intervention by an ad-hoc coalition assembled by J. P. Morgan. In the years 1910–1913, the bankers demanded a central bank to address this structural weakness. Friedman suggested that a similar intervention should have been followed during the banking panic at the end of 1930. This might have stopped the vicious circle of forced liquidation of assets at depressed prices, just as suspension of convertibility in 1893 and 1907 had quickly ended the liquidity crises at the time.[33]

Essentially, in the monetarist view, the Great Depression was caused by the fall of the money supply. Friedman and Schwartz note that "[f]rom the cyclical peak in August 1929 to a cyclical trough in March 1933, the stock of money fell by over a third."[34] The result was what Friedman calls "The Great Contraction"—a period of falling income, prices, and employment caused by the choking effects of a restricted money supply. The mechanism suggested by Friedman and Schwartz was that people wanted to hold more money than the Federal Reserve was supplying. People thus hoarded money by consuming less. This, in turn, caused a contraction in employment and production, since prices were not flexible enough to immediately fall. Friedman and Schwartz argued the Federal Reserve allowed the money supply to plummet because of ineptitude and poor leadership.[35]

Many have since agreed with this theory, including Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 2006 until 2014, who, in a speech honoring Friedman and Schwartz, said:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression, you're right. We did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.[36][37]

Friedman has said that ideally he would prefer to "abolish the Federal Reserve and replace it with a computer."[38] He preferred a system that would increase the money supply at some fixed rate, and he thought that "leaving monetary and banking arrangements to the market would have produced a more satisfactory outcome than was actually achieved through government involvement".[39]

In contrast to Friedman's argument that the Fed did too little to ease after the crisis, Murray Rothbard argued that the crisis was caused by the Fed being too loose in the 1920s in the book America's Great Depression.

Global financial crisis (2007–08)

[edit]

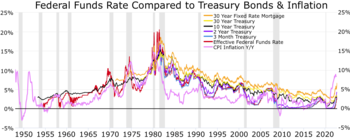

Some economists, such as John B. Taylor,[40] have asserted that the Fed was responsible, at least partially, for the United States housing bubble which occurred prior to the 2007 recession. They claim that the Fed kept interest rates too low following the 2001 recession.[41] The housing bubble then led to the credit crunch. Then-Chairman Alan Greenspan disputes this interpretation. He points out that the Fed's control over the long-term interest rates (to which critics refer) is only indirect. The Fed did raise the short-term interest rate over which it has control (i.e., the federal funds rate), but the long-term interest rate (which usually follows the former) did not increase.[42][43]

The Federal Reserve's role as a supervisor and regulator has been criticized as being ineffective. Former U.S. Senator Chris Dodd, then-chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, remarked about the Fed's role in the 2007-2008 economic crisis, "We saw over the last number of years when they took on consumer protection responsibilities and the regulation of bank holding companies, it was an abysmal failure."

Fractional reserve banking

[edit]The Federal Reserve does not actually control the money supply directly and has delegated this authority to banks. If a bank has a reserve requirement of 10% and they have 10 million dollars in bank deposits, they can create 100 million dollars to loan out to borrowers, or make other investments if it is an investment bank. It is essentially going on margin 10:1 without having to pay interest on the margin, because it is in effect money that they created themselves. According to this critique, this is the primary cause of credit cycles or business cycles, because money supply creation is not under any single entity's control and is decentralized among many banks that are trying to maximize profits individually.[citation needed] The Federal Reserve indirectly controls this process by manipulating the Federal Funds Rate that sets the tone for interest rates on new debt throughout the economy, and intentionally puts the economy into a recession (hard landing) or slow the economy without a recession (soft landing) to tame inflation.[44]

Republican and Tea Party criticism

[edit]During several recent elections, the Tea Party movement has made the Federal Reserve a major point of attack, which has been picked up by Republican candidates across the country. Former Congressman Ron Paul (R) of Texas and his son Senator Rand Paul (R) of Kentucky have long attacked the Fed, arguing that it is hurting the economy by devaluing the dollar. They argue that its monetary policies cause booms and busts when the Fed creates too much or too little fiat money. Ron Paul's book End the Fed repeatedly points out that the Fed engages in money creation "out of thin air."[45] He argued that interest rates should be set by market forces, not by the Federal Reserve.[46] Paul argues that the booms, bubbles and busts of the business cycle are caused by the Federal Reserve's actions.[47]

In the book Paul argues that "the government and its banking cartel have together stolen $0.95 of every dollar as they have pursued a relentlessly inflationary policy." David Andolfatto of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis said the statement was "just plain false" and "stupid" while noting that legitimate arguments can be made against the Federal Reserve.[48] University of Oregon economist Mark Thoma described it as an "absurd" statement which data does not support.[49]

Surveys of economists show overwhelming opposition to abolishing the Federal Reserve or undermining its independence.[50][51] According to Princeton University economist Alan S. Blinder, "mountains of empirical evidence support the proposition that greater central bank independence produces not only less inflation but superior macroeconomic performance, e.g., lower and less volatile inflation with no more volatility in output."[51]

Ron Paul's criticism has stemmed from the influence of the Austrian School of Economics.[52] More specifically, economist Murray Rothbard was a vital figure in developing his views. Rothbard attempted to intertwine both political and economic arguments together in order to make a case to abolish the Federal Reserve. When first laying out his critiques, he writes "The Federal Reserve System is accountable to no one; it has no budget; it is subject to no audit; and no Congressional committee knows of...its operations."[53] This argument from Rothbard is outdated, however, as the Federal Reserve presently does report its balance sheet weekly as well as get audited by outside third parties.[54]

Rothbard also heavily critiques the Federal Reserve being independent from politics despite the Federal Reserve being given both private and public qualities.[54] The acknowledgment of the Federal Reserve being a part of government that exists outside of politics inevitably becomes a "self-perpetuating oligarchy, accountable to no one."[53] This ignores the fact that the Federal Reserve Board of Governors is a federal agency, appointed by the president and Senate.

Money supply should be controlled by Congress

[edit]

In the 1930s, American Catholic priest Charles Coughlin called on Congress to take back control of the money supply, as it is given authority under Article I, Section 8, in the Enumerated Powers, to coin money and regulate the value thereof.[55]

"There is written in the Constitution of the United States that Congress has the right to coin, issue, and regulate the value of money."

— Father Charles Coughlin

Private ownership or control

[edit]According to the Congressional Research Service:

Because the regional Federal Reserve Banks are privately owned, and most of their directors are chosen by their stockholders, it is common to hear assertions that control of the Fed is in the hands of an elite. In particular, it has been rumored that control is in the hands of a very few people holding "class A stock" in the Fed.

As explained, there is no stock in the system, only in each regional Bank. More important, individuals do not own stock in Federal Reserve Banks. The stock is held only by banks who are members of the system. Each bank holds stock proportionate to its capital. Ownership and membership are synonymous. Moreover, there is no such thing as "class A" stock. All stock is the same.

This stock, furthermore, does not carry with it the normal rights and privileges of ownership. Most significantly, member banks, in voting for the directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of which they are a member, do not get voting rights in proportion to the stock they hold. Instead, each member bank regardless of size gets one vote. Concentration of ownership of Federal Reserve Bank stock, therefore, is irrelevant to the issue of control of the system (italics in original).[56]

According to the web site for the Federal Reserve System, the individual Federal Reserve Banks "are the operating arms of the central banking system, and they combine both public and private elements in their makeup and organization."[57] Each of the 12 Banks has a nine-member board of directors: three elected by the commercial banks in the Bank's region, and six chosen – three each by the member banks and the Board of Governors – "to represent the public with due consideration to the interests of agriculture, commerce, industry, services, labor and consumers."[58] These regional banks are in turn controlled by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, whose seven members are nominated by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate.[59]

Member banks ("about 38 percent of the nation's more than 8,000 banks")[60] are required to own capital stock in their regional banks.[60][61] Until 2016, the regional banks paid a set 6% dividend on the member banks' paid-in capital stock (not the regional banks' profits) each year, returning the rest to the US Treasury Department.[62] As of February 24, 2016, member banks with more than $10 billion in assets receive an annual dividend on their paid-in capital stock (Reserve Bank stock) of the lesser of 6% percent and the highest yield of the 10-year Treasury note auctioned at the last auction held prior to the payment of the dividend. Member banks with $10 billion or less in assets continue to be paid a set 6% annual dividend. This change was implemented during the Obama administration in order "to implement the provisions of section 32203 of the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act)".[63] The Fed has noted that this has created "some confusion about 'ownership'":

[Although] the Reserve Banks issue shares of stock to member banks...owning Reserve Bank stock is quite different from owning stock in a private company. The Reserve Banks are not operated for profit, and ownership of a certain amount of stock is, by law, a condition of membership in the System. The stock may not be sold, traded, or pledged as security for a loan….[64]

In his textbook, Monetary Policy and the Financial System, Paul M. Horvitz, the former Director of Research for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, stated,

...the member banks can exert some rights of ownership by electing some members of the Board of Directors of the Federal Reserve Bank [applicable to those member banks]. For all practical purposes, however, member bank ownership of the Federal Reserve System is merely a fiction. The Federal Reserve Banks are not operated for the purpose of earning profits for their stockholders. The Federal Reserve System does earn a profit in the normal course of its operations, but these profits, above the 6% statutory dividend, do not belong to the member banks. All net earnings after expenses and dividends are paid to the Treasury.[65]

In the American Political Science Review, Michael D. Reagan[66] wrote,

...the "ownership" of the Reserve Banks by the commercial banks is symbolic; they do not exercise the proprietary control associated with the concept of ownership nor share, beyond the statutory dividend, in Reserve Bank "profits." ...Bank ownership and election at the base are therefore devoid of substantive significance, despite the superficial appearance of private bank control that the formal arrangement creates.[67][68]

Transparency issues

[edit]One critique is that the Federal Open Market Committee, which is part of the Federal Reserve System, lacks transparency and is not sufficiently audited.[69] A report by Bloomberg News asserts that the majority of Americans believes that the System should be held more accountable or that it should be abolished.[70] Another critique is the contention that the public should have a right to know what goes on in the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings.[71][72][73]

See also

[edit]- America's Great Depression

- Black Friday (1869) Covers the gold scandal of 1869

- The Case Against the Fed

- Causes of the Great Depression

- Criticism of the United States government#Criticism of agencies

- End the Fed

- Federal Reserve Police

- Fractional reserve banking

- Free banking

- Gold standard

- Great Contraction

- Murray Rothbard

References

[edit]- ^ Weissert • •, Will (2012-01-18). "The Gold Standard: Ron Paul Gives New Life to an Old Issue". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Taylor, John B. "Taylor: Federal Reserve Monetary and the Financial Crisis: A Reply to Chairman Ben Bernanke". WSJ. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Wicker, Elmus (2005). The Great Debate On Banking Reform - Nelson Aldrich And The Origins Of The Fed. Ohio State University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 9780814210000.

- ^ a b Johnson, Roger T. (February 2010). "Historical Beginnings... The Federal Reserve" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Murray Rothbard (2007). The Case Against the Fed. Ludwig Von Mises Institute. pp. 27–29, 146. ISBN 978-0945466178.

- ^ Murray Rothbard (2007). The Case Against the Fed. Ludwig Von Mises Institute. p. 146. ISBN 978-0945466178.

- ^ Selgin, George; Lastrapes, William D. (2012). "Has the Fed been a failure?". Journal of Macroeconomics. 34 (3): 569–596. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2012.02.003.

- ^ Salter, Alexander (2014-11-21). "An Introduction to Monetary Policy Rules". Mercatus Center. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- ^ a b "Mr. Market". Hoover Institution. January 30, 1999. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Milton; Schwartz, Anna J. (1986). "Has government any role in money?" (PDF). Journal of Monetary Economics. 17 (1): 37–62. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(86)90005-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-04. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ^ Milton Friedman – Abolish The Fed. Archived from the original (YouTube) on June 11, 2015.

I have long been in favor of abolishing it.

- ^ "My first preference would be to abolish the Federal Reserve" on YouTube

- ^ Friedman, M. (1996). The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory. In Explorations in Economic Liberalism (pp. 3-21). Palgrave Macmillan, London. "It is precisely this leeway, this looseness in the relation, this lack of a mechanical one-to-one correspondence between changes in money and in income that is the primary reason why I have long favored for the USA a quasi-automatic monetary policy under which the quantity of money would grow at a steady rate of 4 or 5 per cent per year, month-in, month-out."

- ^ Salter, A. W. (2014). An Introduction to Monetary Policy Rules. Mercatus Workıng Paper. George Mason University.

- ^ Sheedy, Kevin D. (2014). "Debt and incomplete financial markets: a case for nominal GDP targeting" (PDF). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 45 (1): 301–373. doi:10.1353/eca.2014.0005. S2CID 7642472. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-08. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- ^ Benchimol, Jonathan; Fourçans, André (2019). "Central bank losses and monetary policy rules: a DSGE investigation". International Review of Economics & Finance. 61 (1): 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2019.01.010. S2CID 159290669.

- ^ Sumner, Scott (2012). "The case for nominal GDP targeting". Mercatus Research. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3255027. S2CID 219385932.

- ^ Beckworth, David; Hendrickson, Joshua (2020). "Nominal GDP targeting and the Taylor rule on an even playing field". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 52 (1): 269–286. doi:10.1111/jmcb.12602. S2CID 197772130.

- ^ Cowen, Tyler (2016-08-23). "Why nominal GDP targeting is an especially good idea right now". Marginal Revolution. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- ^ Mullins, Eustace (2009). The Secrets of the Federal Reserve. Bridger House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9656492-1-6. Archived from the original on 2005-11-26. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ^ "Owen criticises reserve board" Archived 2018-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times (July 25, 1921)

- ^ Flaherty, Edward (6 Sep 2000). "Myth #10. The Legendary Tirade of Louis T. McFadden". Political Research Associates. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ McFadden, Louis (June 10, 1932). Congressional Record, June 10, 1932, Louis T. McFadden.

- ^ "Banking: Fight over the Federal Reserve". Time. 14 February 1964. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Uchitelle, Louis (24 August 1989). "Moves On in Congress to Lift Secrecy at the Federal Reserve". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Ron Paul (2009). End the Fed. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 9780446568180.

The Fed was the cause of the Depression.

- ^ E.g., H.R. 2755 (110th Congress); H.R. 2778 (108th Congress); H.R. 5356 (107th Congress); H.R. 1148 (106th Congress)

- ^ "H.R. 2755: Federal Reserve Board Abolition Act". GovTrack.us. 15 June 2007. Archived from the original on 1 January 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "H.R. 459: Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2011". GovTrack.us. 26 January 2011. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Jennifer Bendery (26 July 2012). "Nancy Pelosi: 'Audit The Fed' Bill Is Likely Going Nowhere". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Stiles, Megan (December 18, 2015). "Senate Vote on Audit the Fed Scheduled for January 12th". Campaign for Liberty. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ Milton Friedman; Anna Jacobson Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. xviii, 13. ISBN 978-0691137940.

- ^ Milton Friedman; Anna Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0691137940.

- ^ Milton Friedman; Anna Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0691137940.

- ^ Chang-Tai Hsie; Christina D. Romer (2006). "Was the Federal Reserve Constrained by the Gold Standard During the Great Depression?" (PDF). Journal of Economic History. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-02-22. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ^ Bernanke, Ben S. (8 Nov 2002). "Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke". Federal Reserve. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 1 Jan 2007.

- ^ Milton Friedman; Anna Jacobson Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0691137940. Archived from the original on 2020-01-16. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ O'Toole, Kathleen (9 September 1997). "Greenspan voices concerns about quality of economic statistics". Stanford News Service. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Ebeling, Richard M. (1 March 1999). "Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part 27: Milton Friedman's Second Thoughts on the Costs of Paper Money". fff.org. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Taylor, John B. (10 January 2010). "The Fed and the Crisis: A Reply to Ben Bernanke". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Henderson, David (27 March 2009). "Did the Fed Cause the Housing Bubble?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Jim Lehrer (September 18, 2007). Greenspan Examines Federal Reserve, Mortgage Crunch. PBS Newshour. Alan Greenspan. NewsHour Productions LLC. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Labonte, Marc; Makinen, Gail E. (19 March 2008). "Federal Reserve Interest Rate Changes: 2000-2008" (PDF). assets.opencrs.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Here We Go Again: The Fed is Causing Another Recession". 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Ron Paul (2009). End the Fed. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 9780446568180.

out of thin air.

- ^ "A lonely voice against the Fed now leads a chorus". The Washington Post. 2009. Archived from the original on 2019-01-05. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ "What Happens If We End the Fed?". U.S. News. 2011. Archived from the original on 2019-01-05. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ Andolfatto, David (2011-03-23). "Ron Paul's Money Illusion (Sequel)". MacroMania. Archived from the original on 2019-01-04. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ "Ron Paul's Money Illusion: The Sequel". Economist's View. Archived from the original on 2019-01-05. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ "Fed policy". igmchicago.org. Archived from the original on 2019-01-06. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ a b Blinder, Alan (2010). "How Central Should the Central Bank Be?" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 48: 123–133. doi:10.1257/jel.48.1.123. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Paul, Ron (2011). Mises and Austrian economics : a personal view. Terra Libertas. ISBN 978-1-908089-33-5. OCLC 822300912.

- ^ a b Rothbard, Murray (2007). The Case Against the Fed. Ludwig Von Mises Institute. ISBN 9780945466178.

- ^ a b "The Fed - Does the Federal Reserve ever get audited?". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ "Charles E. Coughlin". Archived from the original on 2018-08-10. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ Woodward, G. Thomas (31 July 1996). "Money and the Federal Reserve System: Myth and Reality". Report No. 96–672 E. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. OCLC 39127005. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ The Federal Reserve System: Purposes and Functions (PDF) (9th ed.). Federal Reserve. June 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "What We Do". New York Fed. March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Federal Reserve Board - Board Members". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Federal Reserve Bank Ownership". Factcheck.org. 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "12 U.S.C. § 282 et seq". Cornell University Law School.

- ^ "12 U.S.C. § 289(a)(1)(A)". Cornell University Law School.

- ^ "Federal Reserve Board issues interim final rule regarding dividend payments on Reserve Bank capital stock". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 18 February 2016. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Who owns the Federal Reserve?". Federal Reserve. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Horvitz, Paul M. (1974). Monetary Policy and the Financial System (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 293. ISBN 9780135998861.

- ^ Not to be confused with Michael Edward Reagan, the son of President Ronald Reagan.

- ^ Reagan, Michael D. (March 1961). "The Political Structure of the Federal Reserve System". American Political Science Review. 55 (1): 64–76. doi:10.2307/1976050. JSTOR 1976050. S2CID 147189298.

- ^ Mittra, S. (1970). Money and Banking: Theory, Analysis, and Policy. New York: Random House. p. 153.

- ^ Poole, William (July 2002). "Untold story of FOMC: Secrecy is exaggerated". St. Louis Federal Reserve. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ Zumbrun, Joshua (9 December 2010). "Majority of Americans Say Fed Should Be Reined In or Abolished, Poll Shows". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 2015-01-27. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ Poole, William (6 October 2004). "FOMC Transparency" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. 87. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: 1–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Remarks by Chairman Alan Greenspan - Transparency in monetary policy". Federal Reserve. 11 October 2001. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "Remarks by Vice Chairman Roger W. Ferguson, Jr.—Transparency in Central Banking: Rationale and Recent Developments". Federal Reserve. 19 April 2001. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

External links

[edit]- New monetary target, Financial Times (registration required)

- The Case Against the Fed PDF book by Murray Rothbard

- The Creature from Jekyll Island PDF book by G. Edward Griffin

- End the Fed PDF book by Ron Paul