324 Bamberga

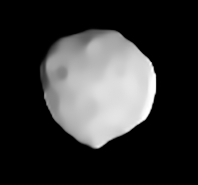

VLT image of Bamberga | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Johann Palisa |

| Discovery date | 25 February 1892 |

| Designations | |

| (324) Bamberga | |

| Pronunciation | /bæmˈbɜːrɡə/ |

Named after | Bamberg |

| Main belt | |

| Adjectives | Bambergian /bæmˈbɜːrdʒiən, -ɡiən/ |

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |

| Epoch 31 July 2016 (JD 2457600.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 124.08 yr (45321 d) |

| Aphelion | 3.59442 AU (537.718 Gm) |

| Perihelion | 1.77023 AU (264.823 Gm) |

| 2.68232 AU (401.269 Gm) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.34004 |

| 4.39 yr (1604.6 d) | |

| 225.419° | |

| 0° 13m 27.682s / day | |

| Inclination | 11.1011° |

| 327.883° | |

| 44.2409° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | c/a = 0.96±0.05[2] |

| 227±3 km[2] 234.67 ± 7.80 km[3] 229.4 ± 7.4 km (IRAS)[4] | |

| Mass | (10.2±0.9)×1018 kg[2] 11×1018 kg[5] (10.3±1.0)×1018 kg[3] |

Mean density | 1.67±0.16 g/cm3[2] 1.52±0.20 g/cm3[3] |

| 1.226 d[6] 29.43 h (1.226 d)[1] | |

| 0.060 (calculated)[2] 0.0628±0.004[4] | |

| C-type asteroid[7] | |

| 6.82[1][4] | |

324 Bamberga is one of the largest asteroids in the asteroid belt. It was discovered by Johann Palisa on 25 February 1892 in Vienna. It is one of the top-20 largest asteroids in the asteroid belt. Apart from the near-Earth asteroid Eros, it was the last asteroid which is ever easily visible with binoculars to be discovered.

Overall Bamberga is the tenth-brightest main-belt asteroid after, in order, Vesta, Pallas, Ceres, Iris, Hebe, Juno, Melpomene, Eunomia and Flora. Its high eccentricity (for comparison 36% higher than that of Pluto), though, means that at most oppositions other asteroids reach higher magnitudes.

Observation

[edit]

Although its very high orbital eccentricity means its opposition magnitude varies greatly, at a rare opposition near perihelion Bamberga can reach a magnitude of +8.0,[8] which is as bright as Saturn's moon Titan. Such near-perihelion oppositions occur on a regular cycle every twenty-two years, with the last occurring in 2013 and the next in 2035, when attaining magnitude 8.1 on 13 September. Its brightness at these rare near-perihelion oppositions makes Bamberga the brightest C-type asteroid, roughly one magnitude brighter than 10 Hygiea's maximum brightness of around +9.1. At such an opposition Bamberga can in fact be closer to Earth than any main-belt asteroid with magnitude above +9.5, getting as close as 0.78 AU. For comparison, 7 Iris never comes closer than 0.85 AU and 4 Vesta never closer than 1.13 AU (when it becomes visible to the naked eye in a light pollution-free sky).

Characteristics

[edit]The 29-hour rotation period is unusually long for an asteroid more than 150 km in diameter.[9] Its spectral class is intermediate between the C-type and P-type asteroids.[7]

10μ radiometric data collected from Kitt Peak in 1975 gave a diameter estimate of 255 km.[10] An occultation of Bamberga was observed on 8 December 1987, and gave a diameter of about 228 km, in agreement with IRAS results. In 1988 a search for satellites or dust orbiting this asteroid was performed using the UH88 telescope at the Mauna Kea Observatories, but the effort came up empty.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 324 Bamberga". 2008-07-26 last obs. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e P. Vernazza et al. (2021) VLT/SPHERE imaging survey of the largest main-belt asteroids: Final results and synthesis. Astronomy & Astrophysics 54, A56

- ^ a b c Carry, B. (December 2012), "Density of asteroids", Planetary and Space Science, vol. 73, pp. 98–118, arXiv:1203.4336, Bibcode:2012P&SS...73...98C, doi:10.1016/j.pss.2012.03.009. See Table 1.

- ^ a b c Tedesco, E.F.; Noah, P.V.; Noah, M.; Price, S.D. (2004). "IRAS Minor Planet Survey. IRAS-A-FPA-3-RDR-IMPS-V6.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 19 January 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V. (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants" (PDF). Solar System Research. 39 (3): 176. Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2008.

- ^ Harris, A. W.; Warner, B.D.; Pravec, P., eds. (2006). "Asteroid Lightcurve Derived Data. EAR-A-5-DDR-DERIVED-LIGHTCURVE-V8.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ a b Neese, C., ed. (2005). "Asteroid Taxonomy.EAR-A-5-DDR-TAXONOMY-V5.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ Donald H. Menzel & Jay M. Pasachoff (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 391. ISBN 0-395-34835-8.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: diameter > 150 (km) and rot_per > 24 (h)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Morrison, D.; Chapman, C. R. (March 1976), "Radiometric diameters for an additional 22 asteroids", Astrophysical Journal, vol. 204, pp. 934–939, Bibcode:2008mgm..conf.2594S, doi:10.1142/9789812834300_0469.

- ^ Gradie, J.; Flynn, L. (March 1988), "A Search for Satellites and Dust Belts Around Asteroids: Negative Results", Abstracts of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, vol. 19, pp. 405–406, Bibcode:1988LPI....19..405G.

External links

[edit]- 324 Bamberga at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 324 Bamberga at the JPL Small-Body Database