The Legend of the Lone Ranger

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

| The Legend of the Lone Ranger | |

|---|---|

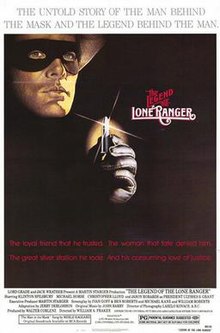

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William A. Fraker |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Characters created by George W. Trendle and Fran Striker |

| Produced by | Walter Coblenz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | László Kovács |

| Edited by | Thomas Stanford |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $13 million[2]–$18 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $12.6 million |

The Legend of the Lone Ranger is a 1981 American Western adventure film directed by William A. Fraker and starring Klinton Spilsbury, Michael Horse and Christopher Lloyd. It is based on the story of The Lone Ranger, a Western character created by George W. Trendle and Fran Striker.

Producers outraged fans by refusing to allow previous Lone Ranger actor Clayton Moore to wear the character's mask during public appearances, and created further bad publicity when it became known that the voice of leading man Spilsbury was dubbed by another actor, James Keach.[5] The film was a critical and commercial failure, and Spilsbury has not appeared in any films since.

Plot

[edit]In 1854 in Texas, the outlaw Butch Cavendish and his gang of outlaws are chasing a young Comanche boy named Tonto. He rides into a thicket and falls off his horse and down an embankment. John Reid, a boy who was already there, hides Tonto, and the outlaws turn their attention to a small village. They kill everyone there, except John. Tonto takes John to his reservation and teaches him to shoot a bow and arrow with precision, how to fight, and overall the way they live.

The two eventually become blood brothers, and John later leaves the reservation for Detroit, grows up to become a lawyer, and takes a stagecoach to a town to set up his law practice. The coach is robbed by Cavendish’s gang, with the shotgun rider getting killed and the driver wounded. John stops the coach and the outlaws take a mailbag containing property deeds.

At the town, John meets the uncle (the owner of the local newspaper) of a beautiful young woman named Amy who was on the same stagecoach as John. John tells them he is going to the Texas Rangers station to visit his brother Dan. During his visit, word reaches them about the whereabouts of Cavendish after some of the gang ride into town during a festival and kill Amy’s uncle. Collins, one of the Rangers, rides ahead to scout for signs of Cavendish, unbeknownst to the Rangers that he is part of Cavendish’s gang. Cavendish and his gang ambush the Rangers (Reid among them), killing all except Reid, who is rescued by Tonto.

When John recovers from his wounds, Tonto teaches him to shoot with silver bullets, and he captures and tames a white horse, which he names Silver. He dedicates his life to fighting the crime that Cavendish represents. To this end, John becomes the great masked western hero, The Lone Ranger. Cavendish takes President Ulysses S. Grant hostage, revealing that he is attempting to take over Texas and secede it from the Union as his own independent country, using the President as a bargaining chip.

John and Tonto sneak into the Cavendish compound and rescue Grant, and blow up the compound with dynamite they found while avoiding the guards. Cavendish attempts to flee the United States Cavalry, but John pursues and ultimately apprehends Cavendish, who is arrested. The President thanks John and Tonto, and the pair ride away as President Grant asks, “Who is that masked man?”

Cast

[edit]- Klinton Spilsbury (James Keach, voice) as John Reid/The Lone Ranger

- Marc Gilpin as young John

- Michael Horse as Tonto[6]

- Patrick Montoya as young Tonto

- Christopher Lloyd as Maj. Bartholomew "Butch" Cavendish[7]

- Matt Clark as Sheriff Wiatt

- Juanin Clay as Amy Striker

- Jason Robards as Ulysses S. Grant

- John Bennett Perry as Ranger Captain Dan Reid

- John Hart as Lucas Striker

- Richard Farnsworth as Wild Bill Hickok

- Ted Flicker as Buffalo Bill Cody

- Merle Haggard as Balladeer

- Lincoln Tate as George A. Custer

- Ted White as Mr. Reid

- Cheré Bryson as Mrs. Reid

- Bonita Granville as Woman (uncredited)

- Cavendish gang

- Buck Taylor as Robert Edward Gattlin

- Tom Laughlin as Neeley

- Robert Hoy as Perlmutter

- Ted Gehring as Dale Wesley Stillwell

- Tom R. Diaz as Eastman

- Chuck Hayward as Wald

- Terry Leonard as Valentine

- Steve Meador as Russell

- Joe Finnegan as Westlake

- Roy Bonner as Richardson

- John M. Smith as Whitloff

- David Hayward as Collins

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The rights to the character had been bought in 1954 by Jack Wrather, an oil billionaire, and his wife Bonita Granville. They had made many attempts to create a Lone Ranger movie that would appeal to a modern audience, including making Tonto an equal partner and mentor to the Lone Ranger. By the late 1970s they believed that the story was ripe for retelling in an epic vein similar to Richard Donner's Superman (1978), with the potential for sequels.[8]

In October 1977 Lew Grade announced he would make the film as part of a slate of movies worth $97 million, including Love and Bullets, Escape to Athena, and Raise the Titanic. Most of the films Grade would finance himself but Lone Ranger was a co production with Wrather. Grade said the Lone Ranger would likely be played by an unknown, after a wide talent search.[9] In October 1978 Grade said the film would be distributed by the new company Associated Film Distribution, a joint consortium between ITC Entertainment, EMI Films, and Marble Arch Productions.[10][11]

"This is a grand old western in the heroic and glorious style of the cowboy picture," said Walter Coblentz, producer. "This is not Blazing Saddles. When he puts on his mask you're going to believe it."[12]

Martin Starger said they were doing the film because "Heroes are needed today more than ever... We're playing it straight. This isn't a spoof or a satire."[13]

Coblentz added, " I decided the Indian element needed upgrading. I decided to treat the Lone Ranger and Tonto more as equals. I wanted their relationship to be dignified. I wanted to take advantage of Indian lore."[14]

In September 1979 Coblentz announced the director would be William Fraker. Fraker was normally a cinematographer but he had directed Monte Walsh which Coblentz admired.[15]

William Fraker the director said "The Lone Ranger will work if we can make him real" and said he was influenced by Lawrence of Arabia.[16]

Two of the movie's four screenwriters, Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts, had previously created the hit TV series Charlie's Angels; they had also worked together on another hit series, Mannix. According to Larry McMurtry, novelist George MacDonald Fraser had written an excellent script for the film,[17] but he was not credited in the finished film.

Casting

[edit]Actors considered for the lead included Stephen Collins, Nicholas Guest, and Bruce Boxleitner. The part eventually went to Klinton Spilsbury, a photographer who had studied art (particularly sculpting) in New York. Spilsbury, whose father was a football coach at the University of Arizona, had grown up on a ranch in Chihuahua, Mexico. Spilsbury signed to a three-picture deal.[12]

"He looked great in the mask, which seems like an odd thing to say,” Starger said. “But that was important because we had to find an actor whose eyes were not close together. The mask doesn’t look good if the eyes are too close.”[18]

Tonto was played by Michael Horse, a silversmith by trade, whose only other acting experience had been a bit part in a Raquel Welch TV-movie. "For me this is an adventure and fun," he said. "Who knows if I can act. I'll soon find out. And if I'm a flop I'll just go off fishing."[12] Horse would later make himself known as a supporting regular on David Lynch's prime-time experimental television series Twin Peaks.

Shooting

[edit]This film was shot in New Mexico, Utah, Colorado and California starting April 1980. Many scenes were shot in Monument Valley, Carson National Forest, Santa Fe National Forest, and Valley of Fire State Park. The fictional border town of Del Rio was constructed twenty miles outside Santa Fe, New Mexico.[10][18]

Spilsbury was reportedly difficult during the shoot. “He came onto the set as if he was playing the role of a movie star,” says Lloyd. “I don’t know whether it was an affectation that he chose to bring with him, or whether he sincerely felt that that’s what was called for. And this was a problem from beginning to end. He did things that simply hindered the production.”[18] This included getting involved in several brawls at night during the shoot.[19]

The movie's ballad-narration, The Man in the Mask, was performed by country music artist Merle Haggard, and composed by John Barry with lyrics written by Dean Pitchford of Footloose and Sing fame.

The filmmakers were unhappy with Spilsbury's acting. "You just never believed what he was saying because he memorized the lines but he had never internalized them,” says Jim Van Wyck, who was a DGA assistant director trainee on the film. “It was like he was reading the script, but the intonations were wrong.”[18] This dialogue was eventually overdubbed for the entire movie by actor James Keach.[20]

"His inflections were a little strange, but I actually didn’t think he was that bad, to be honest with you,” says Keach. “I don’t know why they didn’t have him redo it. But it was a very well-paying job at the time, so I accepted it.”[18]

Five horses were used to play Silver.[21]

The film was part of a brief revival of the Western in 1980, which also included The Long Riders, Heaven's Gate and The Mountain Men.[22]

Clayton Moore lawsuit

[edit]Part of the plan was to shoot a feature film with a new actor to replace the 65-year-old Clayton Moore, who had starred in the long-running and hugely successful television series for much of the 1950s.[23]

Wrather had a vision for the retelling of the story, and he felt that the profile of the character would be devalued by Moore's continuing to appear in costume, as he had done for many years entertaining children in hospitals and appearing at county and state fairs. Also, he did not want audiences to believe that the aging Moore would reprise his role as the Lone Ranger. In 1975, Wrather asked Moore to stop portraying the character, but he refused. In 1979, the producers obtained a court injunction barring Moore from appearing in public with his trademark black mask. He was also permitted to sign autographs only as "The Masked Man." Moore responded by changing his costume slightly and replacing the mask with similar-looking wraparound sunglasses, and by cross-litigating against Wrather. The suit was eventually dismissed. Wrather finally allowed Moore to continue openly playing the character again in 1984 shortly before Wrather's death.[10][24]

“I thought that was really kind of nasty and unnecessary,” said Christopher Lloyd. “Nothing Moore was doing was really interfering with the film. I thought that was kind of terrible.”[18]

Release

[edit]The film was to have initially been released by AFD on December 19, 1980. However, the film was postponed to the summer of 1981 after the 1980 actors strike delayed post-production.[10] AFD shut down in February 1981 after a series of unsuccessful films, particularly Raise the Titanic, and distribution was instead handled by Universal (who would eventually become the owner of the source material itself through its ownership of Classic Media's parent company, DreamWorks Animation[25][26]), along with other Grade movies like On Golden Pond and The Great Muppet Caper.[27] This resulted in the release of the film being pushed back. Spilsbury refused to do any publicity for the film.[28]

Jack Wrather was good friends with Ronald and Nancy Reagan and the Reagans were to attend the premiere at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. Owing the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in March 1981, they did not but Reagan sent a tape record of congratulations to be played at the premiere.[10][29]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was released in 1981 to massive negative publicity over the Clayton Moore lawsuit. The opening week was considered a disaster, making only $4 million after being shown on 1,000 screens.[4] The film ultimately grossed $12 million against its $18 million budget. Other contributing factors were fading public interest in Westerns by the 1980s and alterations to some fundamental elements of the Lone Ranger's character, such as his trademark silver bullets being made into magical talismans in the movie instead of mere symbolism.[30]

Lew Grade, who invested in the movie, had managed to sell it to TV for $7.5 million, and also to HBO.[31]

Marvin Starger claimed the film cost $13 million rather than the reported $18 million but said with advertising and prints costing $10 million the film lost $10 million.[2] Fraker never directed again and Spilsbury never acted again.[18]

Critical

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2014) |

The film received generally mediocre reviews:[32] Time Out London said, "The mystery is how Fraker, a gifted cameraman who made a superb directing debut in Westerns with Monte Walsh, could produce such a clinker as this."[33]

The Los Angeles Times said "you can have a very good time watching it."[34]

In a 1981 episode of the weekly television movie review program, Sneak Previews, film critics Gene Siskel (of the Chicago Sun-Times) and Roger Ebert (of the Chicago Tribune) heavily criticized this film. Siskel stated that the movie was "badly acted and horribly paced." He chastised the tenor of the film, also, stating, "How about having a sense of humor of the character? You know, enjoying the presentation of the character? You don’t get it from the actor Klinton Spilsbury, and you don’t get it from the filmmakers or the director." Siskel, anticipating a short film career for Spilsbury, added this: "I think it [this movie] is going to provide a great trivia question for the 1990s: Not ‘Who was that Masked Man,’ but who played him? The answer Klinton Spilsbury."[35] Both Siskel and Ebert noted how it took an hour for The Legend of the Lone Ranger to really get started. Ebert specifically noted, "It’s very slowly paced, and it should have been break-neck [paced] right out of the starting gate... a real disappointing movie." On behalf of both critics, Siskel summed up the film this way, "Roger [Ebert] and I agree that ‘The Legend of the Lone Ranger’ is a total waste of time... neither one of us can recommend you see it". He refers to it as a "bad Western."[35]

Movie historian Leonard Maltin gave the picture 2 out of a possible 4 stars, noting "Some fine action, great scenery, and a promising storyline; yet these are sabotaged by awkward handling, uncharismatic leads, and an absolutely awful ballad-style narration. Paging Clayton Moore & Jay Silverheels!"[36]

Sir Lew Grade later wrote, in his 1992 autobiography Still Dancing: My Story, that he thought that the problem with the movie was that it took an hour and ten minutes before the Ranger first pulled on his mask. "The mistake was not dispensing with the legend in ten minutes and getting on with the action much earlier on," his text said.[31]

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Raspberry Awards[37] | Worst Picture | Walter Coblenz | Nominated |

| Worst Actor | Klinton Spilsbury[38] | Won | |

| Worst Musical Score | John Barry | Won | |

| Worst Original Song | "The Man in the Mask" Music by John Barry Lyrics by Dean Pitchford |

Nominated | |

| Worst New Star | Klinton Spilsbury | Won | |

| Stinkers Bad Movie Awards[39] | Worst Actor | Won | |

| Worst Song or Song Performance in a Film or Its End Credits | "The Man in the Mask" Music by John Barry Lyrics by Dean Pitchford |

Nominated | |

| Worst Remake | The Legend of the Lone Ranger | Nominated |

Merchandise

[edit]A novelization of the movie, written by Gary McCarthy and published by Ballantine Books, was released in 1981.[40]

The film was adapted into a newspaper comic published between 1981 and 1984 that was written by Cary Bates and illustrated by Russ Heath.[41]

A line of action figures was created by the toy company Gabriel in 1982, including Buffalo Bill Cody, Butch Cavendish, George Custer, The Lone Ranger, and Tonto. Also released by Gabriel were the horses Silver (The Lone Ranger's Horse), Scout (Tonto's Horse), and Smoke (Butch's Horse).

References

[edit]- ^ "The Legend of the Lone Ranger". British Film Institute. London. Archived from the original on January 17, 2009.

- ^ a b MOVIES: PRODUCERS WHO HATCHED THE TURKEYS J M W. Los Angeles Times 15 Apr 1984: t19.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (September 9, 1981). "HOLLYWOOD IS JOYOUS OVER ITS RECORD GROSSING SUMMER". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ a b PRYOR AND ALDA PROVING STARS STILL SELL MOVIES HARMETZ, ALJEAN. New York Times 30 May 1981: 1.10.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (July 2, 2013). "Who was that masked man? The Legend of Klinton Spilsbury". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ Noriyuki, Duane (November 7, 2003). "Art away from Hollywood is where his heart is". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ "THE LEGEND OF THE LONE RANGER DVD Review". Collider. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (June 25, 2013). "1981 'Lone Ranger' Pic Galloped Quickly Into Oblivion".

- ^ FILM CLIPS: Lew Grade's $97 Million Projects Kilday, Gregg. Los Angeles Times 15 Oct 1977: b9.

- ^ a b c d e "The Legend of the Lone Ranger". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ FILM CLIPS: A New Dimension for a Brother Act Kilday, Gregg. Los Angeles Times 28 Oct 1978: b11.

- ^ a b c Hi Yo Silver] It's the Lone Spilsbury] Davis, Ivor. The Globe and Mail 28 May 1980: P.15.

- ^ The Movie Industry Offers Comic Relief For Your Headaches: Coming Films to Star Popeye, Flash Gordon and Tarzan; Sign of Creative Drought? The Movie Industry Offers Comic Relief For Your Headaches By EARL C. GOTTSCHALK JR. Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. Wall Street Journal 12 May 1980: 1.

- ^ MOVIES / BRUCE MCCABE; HOW TONTO BECAME A FULL PARTNER: [FIRST Edition] McCABE, BRUCE. Boston Globe 5 June 1981: 1.

- ^ 'Buffalo' Roams Super Bowl SCHREGER, CHARLES. Los Angeles Times 1 Sep 1979: b4.

- ^ MOVIES: LONE RANGER AND TONTO--THEY'RE COMING THISAWAY MOVIES Greco, Mike. Los Angeles Times 18 May 1980: t6.

- ^ McMurtry, Larry (2010). Hollywood: A Third Memoir. Simon & Schuster. pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g Labrecque, Jeff (July 2, 2013). "The Lone Ranger legend of Klinton Spilsbury". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Terrell, Steve (June 17, 2013). "Santa Fe has storied past with 'Lone Ranger'". The New Mexican.

- ^ "The Legend of the Lone Ranger". DVD Talk. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ HEADING FOR A SILVER ROUNDUP Greco, Mike. Los Angeles Times 18 May 1980: t7.

- ^ Back In The Saddle Again: Hollywood's $100-Million Stampede to Bring Back the Western BACK IN THE SADDLE AGAIN By Pat Dowell. The Washington Post 11 May 1980: H1.

- ^ Stassel, Stephanie (December 29, 1999). "Clayton Moore, TV's 'Lone Ranger,' Dies". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ "Clayton Moore Back In Mask". Chicago Tribune. January 30, 1985. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Verrier, Richard (July 23, 2012). "DreamWorks Animation buys 'Casper,' 'Lassie' parent Classic Media". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "NBCUniversal Announces Acquisition of DreamWorks Animation". Nbcuniversal.com. April 28, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ Film Clips: Show-Biz Segue: From Agent To Studio Chief Pollock, Dale. Los Angeles Times 25 Feb 1981: h1.

- ^ Film Clips: Dick Donner's Next: A Fly-By-Day Fairy Tale, Pollock, Dale. Los Angeles Times 11 Mar 1981: h1

- ^ California Friends Come Calling on Reagans: Wrathers Head for a Round Up Jacobs, Jody. Los Angeles Times 19 May 1981: f2.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (December 29, 1999). "Clayton Moore, Television's Lone Ranger And a Persistent Masked Man, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Lew Grade, Still Dancing: My Story, William Collins & Sons 1987 p 259

- ^ The Legend of the Lone Ranger at IMDb Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ "The Legend of the Lone Ranger | review, synopsis, book tickets, showtimes, movie release date | Time Out London". Timeout.com. November 26, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ LEGENDARY MASKED MAN RIDES AGAIN Thomas, Kevin. Los Angeles Times 21 May 1981: k5.

- ^ a b Siskel & Ebert - Outland, Death Hunt, Take This Job and Shove It, The Legend of the Lone Ranger, retrieved May 24, 2021

- ^ Maltin's TV, Movie, & Video Guide

- ^ "The Golden Raspberry Awards Previous Winners". razzies.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 1998. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "Who was that masked man? The Legend of Klinton Spilsbury - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. July 2, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ "Past Winners Database". August 15, 2007. Archived from the original on August 15, 2007.

- ^ McCarthy, Gary (1981). Legend of the Lone Ranger. Fantasticfiction.co.uk. ISBN 9780345294388. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ "Russ Heath". lambiek.net. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Newman, Kim (1990). Wild West Movies. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-07-47507-47-5.

External links

[edit]- The Legend of the Lone Ranger at IMDb

- The Legend of the Lone Ranger at the TCM Movie Database

- The Legend of the Lone Ranger at Letterboxd

- The Legend of the Lone Ranger at AllMovie

- The Legend of the Lone Ranger at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Legend of the Lone Ranger at Box Office Mojo

- The Legend of the Lone Ranger Action Figures

- 1981 films

- 1981 Western (genre) films

- American Western (genre) films

- Cultural depictions of Buffalo Bill

- Cultural depictions of George Armstrong Custer

- Cultural depictions of Ulysses S. Grant

- Cultural depictions of Wild Bill Hickok

- Day of the Dead films

- Films adapted into comics

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- Films set in Texas

- Films set in 1854

- Films set in the 1870s

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in New Mexico

- Films shot in Utah

- Golden Raspberry Award winning films

- ITC Entertainment films

- Lone Ranger films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by William Roberts (screenwriter)

- 1980s English-language films

- Films directed by William A. Fraker

- 1980s American films

- Stinkers Bad Movie Award winning films

- English-language Western (genre) films