Cyanogen chloride

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Carbononitridic chloride | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Chloroformonitrile | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| Abbreviations | CK | ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.321 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| MeSH | cyanogen+chloride | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1589 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[1] | |||

| CNCl | |||

| Molar mass | 61.470 g mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | acrid | ||

| Density | 2.7683 mg mL−1 (at 0 °C, 101.325 kPa) | ||

| Melting point | −6.55 °C (20.21 °F; 266.60 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 13 °C (55 °F; 286 K) | ||

| soluble | |||

| Solubility | soluble in ethanol, ether | ||

| Vapor pressure | 1.987 MPa (at 21.1 °C) | ||

| -32.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

236.33 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

137.95 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Highly toxic;[2] forms cyanide in the body[3] | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | nonflammable[3] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

none[3] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

C 0.3 ppm (0.6 mg/m3)[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[3] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | inchem.org | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanenitriles

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

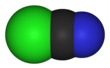

Cyanogen chloride is a highly toxic chemical compound with the formula CNCl. This linear, triatomic pseudohalogen is an easily condensed colorless gas. More commonly encountered in the laboratory is the related compound cyanogen bromide, a room-temperature solid that is widely used in biochemical analysis and preparation.

Synthesis, basic properties, structure

[edit]Cyanogen chloride is a molecule with the connectivity Cl−C≡N. Carbon and chlorine are linked by a single bond, and carbon and nitrogen by a triple bond. It is a linear molecule, as are the related cyanogen halides (NCF, NCBr, NCI). Cyanogen chloride is produced by the oxidation of sodium cyanide with chlorine. This reaction proceeds via the intermediate cyanogen ((CN)2).[4]

The compound trimerizes in the presence of acid to the heterocycle called cyanuric chloride.

Cyanogen chloride is slowly hydrolyzed by water at neutral pH to release cyanate and chloride ions:

Applications in synthesis

[edit]Cyanogen chloride is a precursor to the sulfonyl cyanides[5] and chlorosulfonyl isocyanate, a useful reagent in organic synthesis.[6]

Further chlorination gives the isocyanide dichloride.

Safety

[edit]Also known as CK, cyanogen chloride is a highly toxic blood agent, and was once proposed for use in chemical warfare. It causes immediate injury upon contact with the eyes or respiratory organs. Symptoms of exposure may include drowsiness, rhinorrhea (runny nose), sore throat, coughing, confusion, nausea, vomiting, edema, loss of consciousness, convulsions, paralysis, and death.[2] It is especially dangerous because it is capable of penetrating the filters in gas masks, according to United States analysts. CK is unstable due to polymerization, sometimes with explosive violence.[7]

Chemical weapon

[edit]Cyanogen chloride is listed in schedule 3 of the Chemical Weapons Convention: all production must be reported to the OPCW.[8]

By 1945, the U.S. Army's Chemical Warfare Service developed chemical warfare rockets intended for the new M9 and M9A1 Bazookas. An M26 Gas Rocket was adapted to fire cyanogen chloride-filled warheads for these rocket launchers.[9] As it was capable of penetrating the protective filter barriers in some gas masks,[10] it was seen as an effective agent against Japanese forces (particularly those hiding in caves or bunkers) because their standard issue gas masks lacked the barriers that would provide protection against cyanogen chloride.[9][11][12] The US added the weapon to its arsenal, and considered using it, along with hydrogen cyanide, as part of Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan, but President Harry Truman decided against it, instead using the atomic bombs developed by the secret Manhattan Project.[13] The CK rocket was never deployed or issued to combat personnel.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ a b "CYANOGEN CHLORIDE (CK)". The Emergency Response Safety and Health Database. NIOSH. 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0162". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Coleman, G. H.; Leeper, R. W.; Schulze, C. C. (1946). "Cyanogen Chloride". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 2. pp. 90–94. doi:10.1002/9780470132333.ch25. ISBN 9780470132333.

- ^ Vrijland, M. S. A. (1977). "Sulfonyl Cyanides: Methanesulfonyl Cyanide" (PDF). Organic Syntheses. 57: 88; Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 727.

- ^ Graf, R. (1966). "Chlorosulfonyl Isocyanate" (PDF). Organic Syntheses. 46: 23; Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 226.

- ^ FM 3-8 Chemical Reference Handbook. US Army. 1967.

- ^ "Schedule 3". www.opcw.org. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Smart, Jeffrey (1997), "2", History of Chemical and Biological Warfare: An American Perspective, Aberdeen, MD, USA: Army Chemical and Biological Defense Command, p. 32.

- ^ "Cyanogen chloride (CK): Systemic Agent | NIOSH | CDC". 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Characteristics and Employment of Ground Chemical Munitions", Field Manual 3-5, Washington, DC: War Department, 1946, pp. 108–19

- ^ Skates, John R (2000), The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb, University of South Carolina Press, pp. 93–96, ISBN 978-1-57003-354-4

- ^ Binkov's Battlegrounds (27 April 2022). "How would have WW2 gone if the US had not used nuclear bombs on Japan?". YouTube.Com. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

External links

[edit]- Murphy-Lavoie, H. (2011). "Cyanogen Chloride Poisoning". EMedicine. MedScape.

- "National Pollutant Inventory – Cyanide compounds fact sheet". Australian Government.

- "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.